I just realized that I’ve never written about Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

This weekend seems the right time to fill that gap.

I haven’t written about the man for obvious reasons: I am not qualified to do it. I don’t know enough about his legacy or his impact on the US or on the fight for civil rights; I know what everybody else knows, and not much more. I don’t know enough of his philosophy or his writing to speak informatively and usefully about either; I know something, but not enough — and there are books out there about all of this, so I have not enough to add to that.

But there is one thing I can write about (and therefore should: because all that any of us can do is add our own unique perspectives on things to the conversation. Even if my insights are not the greatest insights, still they are mine; bringing them up can help inform or influence other people, or inform or influence the conversation, in positive ways. If we want people to stop talking about nonsense like which kind of stove we are allowed to use, then we need to make an effort to shift the conversation away from nonsense, and onto things that matter more.): and that is Dr. King’s rhetoric. (I should maybe make this a podcast episode. I don’t know if I’m ever going to continue my podcast, or if I should, but if I do, this would be a good subject.)

I don’t know that I studied his rhetoric very carefully in high school. I remember hearing the “I Have a Dream” speech. I remember that my high school choir sang what our director told us was Dr. King’s favorite spiritual, “Precious Lord.” (Can’t do it better than Mahalia Jackson.) I remember being shocked when I heard that the state where I currently live — which thought never not once crossed my mind, that I would eventually become a goddamn high school teacher in Arizona — was the only one in the country not to recognize Dr. King’s birthday as a national holiday. (Can’t do it better than Public Enemy.) I mean, who would refuse a Monday off? And who wouldn’t want to celebrate the life and work of Dr. King? But I don’t remember reading “Letter from Birmingham Jail.” Not until I got to Arizona, and found out it was part of the standard curriculum at my school, and also that an excerpt from it was in the packet on syntax as a rhetorical strategy which I got as part of my training to become an AP English teacher.

So now I’ve been teaching the Letter from Birmingham Jail as part of two of my classes, Sophomore English, when we study argument, and AP Language, when we study rhetoric — specifically, syntax, the arrangement of words into sentences and sentences into paragraphs, and how that arrangement affects meaning. And as with everything I teach, the more I teach it, the more I learn about it: and in the case of Dr. King’s essay, the more I grow to revere the man who was capable of writing it.

So let me explain why.

First: context. This is the information I give to my students when we study the piece. There is some historical information; then two pieces written by white clergymen in Birmingham in the 1960s: “An Appeal for Law and Order and Common Sense,” which I include because the open letter written by the eight clergymen references it — and because it is a fascinating piece — and then the Public Statement by Eight Alabama Clergymen, which was the precipitating event for Dr. King’s masterwork, as the background explains. Remember that, although the Public Statement doesn’t name Dr. King, he is the target of it: he is that “outside agitator” they mention.

BACKGROUND INFORMATION FOR “LETTER FROM BIRMINGHAM JAIL” BY THE REVEREND DR. MARTIN LUTHER KING, JR.

APR 16, 2013

On its 50th anniversary, take a look back at a seminal text On April 12, King and nearly 50 other protestors and civil rights leaders (including Ralph Abernathy and Fred Shuttlesworth) had been arrested after leading a Good Friday demonstration as part of the Birmingham Campaign, designed to bring national attention to the brutal, racist treatment suffered by blacks in one of the most segregated cities in America—Birmingham, Alabama. For months, an organized boycott of the city’s white-owned-and-operated businesses had failed to achieve any substantive results, leaving King and others convinced they had no other options but more direct actions, ignoring a recently passed ordinance that prohibited public gathering without an official permit. For King, this arrest—his 13th—would become one of the most important of his career. Thrown into solitary confinement, King was initially denied access to his lawyers or allowed to contact his wife, until President John F. Kennedy was urged to intervene on his behalf. As previously agreed upon, King was not immediately bailed out of jail by his supporters, having instead agreed to a longer stay in jail to draw additional attention to the plight of black Americans.

Shortly after King’s arrest, a friend smuggled in a copy of an April 12 Birmingham newspaper which included an open letter, written by eight local Christian and Jewish religious leaders, which criticized both the demonstrations and King himself, whom they considered an outside agitator. Isolated in his cell, King began working on a response. Without notes or research materials, King drafted an impassioned defense of his use of nonviolent, but direct, actions. Over the course of the letter’s 7,000 words, he turned the criticism back upon both the nation’s religious leaders and more moderate-minded white Americans, castigating them for sitting passively on the sidelines while King and others risked everything agitating for change. King drew inspiration for his words from a long line of religious and political philosophers, quoting everyone from St. Augustine and Socrates to Thomas Jefferson and then-Chief Justice of the United States Earl Warren, who had overseen the Supreme Court’s landmark civil rights ruling in Brown v. Board of Education. For those, including the Birmingham religious leaders, who urged caution and remained convinced that time would solve the country’s racial issues, King reminded them of Warren’s own words on the need for desegregation, “justice too long delayed is justice denied.” And for those who thought the Atlanta-based King had no right to interfere with issues in Alabama, King argued, in one of his most famous phrases, that he could not sit “idly by in Atlanta” because “injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.” Without writing papers, King initially began by jotting down notes in the margin of the newspaper itself, before writing out portions of the work on scraps of paper he gave his attorneys, allowing a King ally, Wyatt Walker, to begin compiling the letter, which eventually ran to 21 double-spaced, typed pages. Curiously, King never sent a copy to any of the eight Birmingham clergy who he had “responded” to, leaving many to believe that he had intended it to have a much broader, national, audience all along.

King was finally released from jail on April 20, four days after penning the letter. Despite the harsh treatment he and his fellow protestors had received, King’s work in Birmingham continued. Just two weeks later, more than 1,000 schoolchildren took part in the famed “Children’s Crusade,” skipping school to march through the city streets advocating for integration and racial equality. Birmingham’s Commissioner of Public Safety Eugene “Bull” Connor, who King had repeatedly criticized in his letter for his harsh treatment, ordered fire hoses and police dogs be turned on the young protestors; more than 600 of them were jailed on the first day alone. The brutal and cruel police tactics on display in Alabama were broadcast on televisions around the world, horrifying many Americans. With Birmingham in chaos and businesses shuttered, local officials were forced to meet with King and agree to some, but not all, of his demands. On June 11, with the horrific events in Birmingham still seared on the American consciousness, and following Governor George Wallace’s refusal to integrate the University of Alabama until the arrival of the U.S. National Guard, President Kennedy addressed the nation, announcing his plans to present sweeping civil rights legislation to the U.S. Congress. Kennedy’s announcement, however, did little to quell the unrest in Birmingham and on September 15, 1963, a Ku Klux Klan bombing at the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church left four young African-American girls dead.

By this time, King’s Letter from Birmingham Jail had begun to appear in publications across the country. Months earlier, Harvey Shapiro, an editor at The New York Times, had urged King to use his frequent jailing as an opportunity to write a longer defense of his use of nonviolent tactics, and though King did so, The New York Times chose not to publish it. Others did, including the Atlantic Monthly and The Christian Century, one of the most prominent Protestant magazines in the nation. In the weeks leading up to the March on Washington, King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference used the letter as part of its fundraising efforts, and King himself used it as a basis for a book, “Why We Can’t Wait,” which looked back upon the successes and failures of the Birmingham Campaign. The book was released in July 1964, the same month that the landmark Civil Rights Act was signed into law by President Lyndon Johnson.

Today, 50 years after it was written, King’s powerful message continues to resonate around the world–the letter is part of many American school curriculums, has been included in more than 50 published anthologies and has been translated into more than 40 languages. In April 2013, a group of Protestant clergy released an official—albeit considerably delayed—response to King’s letter. Published in The Christian Century, one of the first publications to carry King’s own words, the letter continues King’s call to religious leaders around the world to intervene in matters of racial, social and economic justice.

An Appeal for Law and Order and Common Sense

In these times of tremendous tensions, and change in cherished patterns of life in our beloved Southland, it is essential that men who occupy places of responsibility and leadership shall speak concerning their honest convictions.

We the undersigned clergymen have been chosen to carry heavy responsibility in our religious groups. We speak in a spirit of humility, and only for ourselves. We do not pretend to know all the answers, for the issues are not simple. Nevertheless, we believe our people expect and deserve leadership from us, and we speak with firm conviction for we do know the ultimate spirit in which all problems of human relations must be solved.

It is clear that a series of court decisions will soon bring about desegregation of certain schools and colleges in Alabama. Many sincere people oppose this change and are deeply troubled by it. As southerners, we understand this. We nevertheless feel that defiance is neither the right answer nor the solution. And we feel that inflammatory and rebellious statements can lead only to violence, discord, confusion, and disgrace for our beloved state.

We therefore affirm, and commend to our people:

1. That hatred and violence have no sanction in our religious and political traditions.

2. That there may be disagreement concerning laws and social change without advocating defiance, anarchy, and subversion.

3. That laws may be tested in courts or changed by legislatures, but not ignored by whims of individuals.

4. That constitutions may be amended or judges impeached by proper action, but our American way of life depends upon obedience to the decisions of courts of competent jurisdiction in the meantime.

5. That no person’s freedom is safe unless every person’s freedom is equally protected.

6. That freedom of speech must at all costs be preserved and exercised without fear of recrimination or harassment.

7. That every human being is created in the image of God and is entitled to respect as a fellow human being with all basic rights, privileges, and responsibilities which belong to humanity.

We respectfully urge those who strongly oppose desegregation to pursue their convictions in the courts, and in the meantime peacefully to abide by the decisions of those same courts. We recognize that our problems cannot be solved in our strength or on the basis of human wisdom alone. The situation that confronts us calls for earnest prayer, for clear thought, for understanding love, and For courageous action. Thus we call on all people of goodwill to join us in seeking divine guidance as we make our appeal for law and order and common sense.

PUBLIC STATEMENT BY EIGHT ALABAMA CLERGYMEN

April 12, 1963

We the undersigned clergymen are among those who, in January, issued “An Appeal for Law and Order and Common Sense,” in dealing with racial problems in Alabama. We expressed understanding that honest convictions in racial matters could properly be pursued in the courts, but urged that decisions of those courts should in the meantime be peacefully obeyed.

Since that time there had been some evidence of increased forbearance and a willingness to face facts. Responsible citizens have undertaken to work on various problems which cause racial friction and unrest. In Birmingham, recent public events have given indication that we all have opportunity for a new constructive and realistic approach to racial problems.

However, we are now confronted by a series of demonstrations by some of our Negro citizens, directed and led in part by outsiders. We recognize the natural impatience of people who feel that their hopes are slow in being realized. But we are convinced that these demonstrations are unwise and untimely.

We agree rather with certain local Negro leadership which has called for honest and open negotiation of racial issues in our area. And we believe this kind of facing of issues can best be accomplished by citizens of our own metropolitan area, white and Negro, meeting with their knowledge and experience of the local situation. All of us need to face that responsibility and find proper channels for its accomplishment.

Just as we formerly pointed out that “hatred and violence have no sanction in our religious and political traditions,” we also point out that such actions as incite to hatred and violence, however technically peaceful those actions may be, have not contributed to the resolution of our local problems. We do not believe that these days of new hope are days when extreme measures are justified in Birmingham.

We commend the community as a whole, and the local news media and law enforcement in particular, on the calm manner in which these demonstrations have been handled. We urge the public to continue to show restraint should the demonstrations continue, and the law enforcement official to remain calm and continue to protect our city from violence.

We further strongly urge our own Negro community to withdraw support from these demonstrations, and to unite locally in working peacefully for a better Birmingham. When rights are consistently denied, a cause should be pressed in the courts and in negotiations among local leaders, and not in the streets. We appeal to both our white and Negro citizenry to observe the principles of law and order and common sense.

C. C. J. Carpenter, D.D., LL.D. Bishop of Alabama

Joseph A. Durick, D.D., Auxiliary Bishop, Diocese of Mobile, Birmingham

Rabbi Hilton L. Grafman, Temple Emanu-El, Birmingham, Alabama

Bishop Paul Hardin, Bishop of the Alabama-West Florida Conference

Bishop Nolan B. Harmon, Bishop of the North Alabama Conference of the Methodist Church

George M. Murray, D.D., LL.D., Bishop Coadjutor, Episcopal Diocese of Alabama

Edward V. Ramage, Moderator, Synod of the Alabama Presbyterian Church in the United States

Earl Stallings, Pastor, First Baptist Church, Birmingham, Alabama

So that’s why Dr. King wrote the letter. And I appreciate the irritation that made him do it — even though, as was described above, he had been looking for an opportunity to explain his understanding of his actions more fully; still, the decision to do this while he was in jail was surely due to his irritation at this particular statement by these particular men, because this would have been much easier to do when he was at his home, in his office, where he was comfortable writing. (Though he was probably able to focus better while he was in jail; similar to Malcolm X, who was able to teach himself to read and write and think while in prison because he had nothing else to do — I think I’ve said before that boredom can be useful) The fact that he was capable of producing this incredible work while in a jail cell says, better than any words I could come up with, how amazing Dr. King was.

Let me show you.

(I’m not going through the whole letter: it’s almost 20 pages long. I struggle with the decision to read the whole thing in class; I know the students completely lose focus before the end of it, but it’s just so damn good, I hate to stop reading it before the finish. Generally I read the whole thing and then only teach to a certain point: I’ll cover the same section now. And put a link to the whole letter, if anyone wants to read that. It is all good.)

Here’s how he starts:

My Dear Fellow Clergymen:

While confined here in the Birmingham city jail, I came across your recent statement calling my present activities “unwise and untimely.” Seldom do I pause to answer criticism of my work and ideas. If I sought to answer all the criticisms that cross my desk, my secretaries would have little time for anything other than such correspondence in the course of the day, and I would have no time for constructive work. But since I feel that you are men of genuine good will and that your criticisms are sincerely set forth, I want to try to answer your statement in what I hope will be patient and reasonable terms.

See why I say he was driven to write this because of irritation? Look at the subtle shade he throws here: starting with the matter-of-fact description of coming across the Public Statement while he happened to be in jail, which conflicts with the address to My Dear Fellow Clergymen, the contrast showing the difference between them, that though they are all clergymen, only one of them is in jail; then the not-very-subtle flex about how he seldom answers criticism: because of course he gets more criticism than these men could even dream of, and theirs is hardly the worst or the most significant of Dr. King’s critiques; he is a national figure, after all. And then the comment about his secretaries, plural, who would not have time to do constructive work — clearly putting this whole exchange into the realm of non-constructive work, along with showing how much more busy and important Dr. King is, with his large staff and his extensive constructive correspondence: all of which has come to a halt because he is currently confined in jail. So, hey, why not write back to these gentlemen? Who, he feels (but does not know, because it is not clear that they are, based on the two statements essentially in support of segregation and racism) are sincere men of goodwill? So he will try to show that he can be “patient and reasonable,” a direct reply to their criticism which he quoted, calling his actions “unwise and untimely.” And what follows is a perfectly crafted, 7,000-word shellacking of these jerks, their state, their government, their churches, their very souls, published only a week after their shallow little gripe.

So he begins:

I think I should indicate why I am here in Birmingham, since you have been influenced by the view which argues against “outsiders coming in.” I have the honor of serving as president of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, an organization operating in every southern state, with headquarters in Atlanta, Georgia. We have some eighty five affiliated organizations across the South, and one of them is the Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights. Frequently we share staff, educational and financial resources with our affiliates. Several months ago the affiliate here in Birmingham asked us to be on call to engage in a nonviolent direct action program if such were deemed necessary. We readily consented, and when the hour came we lived up to our promise. So I, along with several members of my staff, am here because I was invited here. I am here because I have organizational ties here.

Notice the polite way he pretends that their argument is not their thought, but only that they were influenced by others who held the view that he is an outsider. Notice also how he quotes that phrase, in order to refuse it legitimacy; these aren’t his words, these are the words that were thrown at him, and which these good men have unfortunately repeated. Why is here, in Birmingham? (And though he doesn’t say it, the corollary “Why am I in your jail?” echoes through this entire section, leaving them to answer that question themselves) Because he was invited here by members of his larger organization; the very same people they addressed in their own letter to the people of Birmingham, the “Negro community” and its leadership.

And that’s enough reason, of course. Hard to call someone an outsider when they were invited by insiders. And let’s note, as Dr. King points out, that his organization is headquartered in Atlanta, Georgia. Which is in the next state. It’s 147 miles away. Google Maps says the drive would take about two hours. Boston to NYC is 211 miles. San Francisco to LA (both in the same state) is 383.

But Dr. King doesn’t stop there: having made a reasonable response to the accusation — which is lame, anyway; calling Dr. King an outsider in order to delegitimize his argument is a logical fallacy called Poisoning the Well; the source of the argument is bad, so the argument must be bad, which of course doesn’t follow, because the dumbest person in the world can say the smartest thing — he makes a second rebuttal to the claim, one that is more directed at his specific opponents here:

But more basically, I am in Birmingham because injustice is here. Just as the prophets of the eighth century B.C. left their villages and carried their “thus saith the Lord” far beyond the boundaries of their home towns, and just as the Apostle Paul left his village of Tarsus and carried the gospel of Jesus Christ to the far corners of the Greco Roman world, so am I compelled to carry the gospel of freedom beyond my own home town. Like Paul, I must constantly respond to the Macedonian call for aid.

This is a more abstract argument, because the first is very plain and straightforward; this one uses a religious allusion to make an analogy. It’s a damn fine religious allusion — and actually, it’s two, because one of the eight clergymen who signed the Public Statement was a rabbi, so first he refers to the Jewish prophets of the Old Testament, and then he refers to the Apostle Paul, for the seven Christian ministers who signed the statement: but in both cases, he equates himself with the carriers of the Gospel, those spreading the word of God: which would make those who oppose him the Babylonians, or the Romans: basically the enemies of God. Neither is a good association for a clergyman to accept. But if you accept that there is injustice in Birmingham, then his intent to oppose the injustice has to be seen as a good thing, which obviously has to put him in line with the will of God. What clergyman could oppose the “gospel of freedom?”

This should be enough to shut them up — and it might have been; I don’t know how much the eight clergymen shrunk when they read Dr. King’s letter. (Imagine that, though. If a nationally recognized figure wrote directly to you. To tell you why you’re wrong. For almost 20 pages.) But he’s STILL not done. Think about that. Think about how hard it is to come up with one good response to an argument that somebody makes to you. Think how much we all struggle in forming actual, reasonable replies, particularly to unreasonable people, who do stupid things like call us carpetbaggers, which is the association the Birmingham clergymen were probably trying to make in calling Dr. King an “outside agitator.” Just one clapback is really all we can ask of ourselves. But Dr. King? He has three.

Moreover, I am cognizant of the interrelatedness of all communities and states. I cannot sit idly by in Atlanta and not be concerned about what happens in Birmingham. Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere. We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly. Never again can we afford to live with the narrow, provincial “outside agitator” idea. Anyone who lives inside the United States can never be considered an outsider anywhere within its bounds.

I mean, “moreover” is just kinda mean. How do you argue with people who talk like that, and do it right? “I am cognizant” implies both that you are not, and that you should be. And then Dr. King shows that he was one of the greatest wordsmiths since Abraham Lincoln: he creates not one, not two, but three different phrases that became legendary: “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.” “We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny.” “Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly.”

They’re all beautiful phrases: two of them perfect examples of parallel structure, putting similar phrases next to each other in order to create echoes and emphasis through repetition, combined with discernible differences made clearer by the juxtaposition; and in between a beautiful and powerful metaphor that makes clear an abstract but inspiring idea of humanity, a vast network of mutuality. It’s amazing writing. And while King’s opponents are reeling from that — again, imagine if a national figure, an international figure to be if he wasn’t yet (this was all prior to the March on Washington, but King was certainly already extremely well known; let me point out that the goddamn president of the United States intervened on King’s behalf to get him access to his attorneys while he was in jail) — he closes down the argument, by pointing out that we are all Americans, and the idea of an “outside agitator” from the same country is narrow, provincial thinking (read: stupid) that just doesn’t make any sense.

All right: having trashed the eight clergymen’s first claim, King moves on to his main argument: that his actions were neither “unwise” nor “untimely.” He introduces his argument here:

You deplore the demonstrations taking place in Birmingham. But your statement, I am sorry to say, fails to express a similar concern for the conditions that brought about the demonstrations. I am sure that none of you would want to rest content with the superficial kind of social analysis that deals merely with effects and does not grapple with underlying causes. It is unfortunate that demonstrations are taking place in Birmingham, but it is even more unfortunate that the city’s white power structure left the Negro community with no alternative.

Look at how polite he is: he is disappointed that they failed to recognize the real problem, which is the root cause of the demonstrations rather than the demonstrations themselves — but he doesn’t say he’s disappointed in the clergymen; it’s only their statement that “fails.” He is sure that none of those good, sincere men would be satisfied with “the superficial kind of social analysis” that doesn’t focus on root causes. He knows, as they know, as we all know, that they are indeed focused only on the superficial symptoms of the problem rather than the root causes; their entire argument is that everyone should calm down, not that anyone should try to solve the problem. And then he imitates their passive voice, their passive-aggressive tone, by stating “it is unfortunate” that bad things are happening — but it’s much worse (sorry, “even more unfortunate”) that the white people caused those bad things. Isn’t it?

Of course it is.

So then King gives the description of the four steps of a nonviolent campaign: “collection of the facts to determine whether injustices exist; negotiation; self purification; and direct action.” And then slowly, painstakingly, he goes through all of these steps in the letter. He refers to the city’s history of not only segregation but also violence — which his opponents have to stipulate, since that same violence was the root cause of their statements, and their first statement clearly asks the white people of Birmingham to stop causing problems and let the issues be worked out by the courts. (And please note that all of this exchange happened before the Children’s Crusade, which led to the famous and terrible footage of the Birmingham police using firehoses and police dogs to attack children peacefully protesting, and also before the KKK bombing of the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church which murdered four young girls. So yes, I think we can fucking well stipulate that Birmingham was a violent and racist place.) He then explains how the local community tried to negotiate, and the white people in Birmingham were the reason the negotiations failed. He talks about their attempts at self purification, and then he talks about their decision to move to direct action.

Then he talks about how the delayed their direct action. For the mayoral election. Which, one would think, would be a perfect opportunity for an agitator — perhaps a secret Communist, as King was absurdly accused of being several times — to cause as much disruption as possible, and have a large impact on the community. But they didn’t do that. And then when there was a runoff — even though one of the candidates in the runoff was Eugene “Bull” Connor, the Commissioner of Public Safety who would later order the firehoses turned on children — they delayed their protest march again.

What were those guys saying about “unwise and untimely?”

Right.

He ends this portion of the argument following the same pattern he established in the beginning, with the rebuttal of the “outside agitator” accusation: first a straightforward, concrete refutation based on facts (“I was invited here,” in that first instance), and then he expands the discussion into larger, more abstract, but also more important ideas. (“Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.”) In this case he says this:

You may well ask: “Why direct action? Why sit ins, marches and so forth? Isn’t negotiation a better path?” You are quite right in calling for negotiation. Indeed, this is the very purpose of direct action. Nonviolent direct action seeks to create such a crisis and foster such a tension that a community which has constantly refused to negotiate is forced to confront the issue. It seeks so to dramatize the issue that it can no longer be ignored. My citing the creation of tension as part of the work of the nonviolent resister may sound rather shocking. But I must confess that I am not afraid of the word “tension.” I have earnestly opposed violent tension, but there is a type of constructive, nonviolent tension which is necessary for growth. Just as Socrates felt that it was necessary to create a tension in the mind so that individuals could rise from the bondage of myths and half truths to the unfettered realm of creative analysis and objective appraisal, so must we see the need for nonviolent gadflies to create the kind of tension in society that will help men rise from the dark depths of prejudice and racism to the majestic heights of understanding and brotherhood.

I love this because he points out the hypocrisy of the White community in Birmingham asking for peaceful negotiations, and thus turns the argument around on them. It’s like he’s saying, “Negotiation? We would love to negotiate! Let’s negotiate!” And by so doing he calls their bluff, because of course, it is not the Black community that refused to talk about these issues. And then he gives us this amazing, dry, sarcastic discussion of “tension,” which I love because I love knowing that Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., was a smartass: “I confess that I am not afraid of the word ‘tension.'” The idea that he is confessing to something that should be plainly, easily, universally true: because what the hell is scary about the word “tension?” In fact, “tension” is necessary and important for change; and he then refers to Socrates, equating himself to the father of philosophy, the man famously convicted wrongly by his city’s establishment, and executed when he had committed no real crime other than creating “tension.” And his magnificent gift with words shows in the ultimate goal of that creation of tension: “the kind of tension in society that will help men rise from the dark depths of prejudice and racism to the majestic heights of understanding and brotherhood.” Beautiful. And, what, are you saying you would be against that? You wouldn’t want that? Because you’re afraid of tension?

Not satisfied with simply having shown that the protestors were not impatient or “untimely” in their marching, King takes this chance to explain to everyone everywhere why the civil rights movement isn’t willing to wait. And this is where my AP Lang class picks up this thread. First, King says this:

We know through painful experience that freedom is never voluntarily given by the oppressor; it must be demanded by the oppressed. Frankly, I have yet to engage in a direct action campaign that was “well timed” in the view of those who have not suffered unduly from the disease of segregation. For years now I have heard the word “Wait!” It rings in the ear of every Negro with piercing familiarity. This “Wait” has almost always meant “Never.” We must come to see, with one of our distinguished jurists, that “justice too long delayed is justice denied.”

Here King is not speaking to the clergymen. The language is too aggressive: oppressor and oppressed, while absolutely the accurate terms here, are not words that will appeal to the nice churchmen who want peace and quiet. Here King is speaking to everyone who has said the civil rights movement is pushing too hard, and going too fast; and the man is tired of talking about this. And again, he makes the same point successfully, several times, which just shows the pathetic weakness of the initial claim, that the civil rights movement is going too fast and should instead just wait for things to work out. His first statement makes an entirely valid point: oppressors do not give away power, they do not simply let people go. Which makes the claim ridiculous, because why wait for something that will never happen on its own? Then his second comment, starting with “Frankly,” in which you can hear his irritation with this whole discussion, points out that people who stand to lose power are not the ones who should get to decide when the oppressed should demand their freedom. Then he raises this to an eternal, universal experience that every oppressed African-American in the US has had to deal with, has been pierced by the ring of, this word “Wait.” And he refers to Supreme Court Chief Justice Earl Warren, writing in the Brown v. Board of Education decision, that “justice too long delayed is justice denied,” the Chief Justice’s own poetic truism.

That’s three reasons why “Wait” is a stupid argument to apply to the civil rights movement. But then, King does this:

We have waited for more than 340 years for our constitutional and God given rights. The nations of Asia and Africa are moving with jetlike speed toward gaining political independence, but we still creep at horse and buggy pace toward gaining a cup of coffee at a lunch counter. Perhaps it is easy for those who have never felt the stinging darts of segregation to say, “Wait.” But when you have seen vicious mobs lynch your mothers and fathers at will and drown your sisters and brothers at whim; when you have seen hate filled policemen curse, kick and even kill your black brothers and sisters; when you see the vast majority of your twenty million Negro brothers smothering in an airtight cage of poverty in the midst of an affluent society; when you suddenly find your tongue twisted and your speech stammering as you seek to explain to your six year old daughter why she can’t go to the public amusement park that has just been advertised on television, and see tears welling up in her eyes when she is told that Funtown is closed to colored children, and see ominous clouds of inferiority beginning to form in her little mental sky, and see her beginning to distort her personality by developing an unconscious bitterness toward white people; when you have to concoct an answer for a five year old son who is asking: “Daddy, why do white people treat colored people so mean?”; when you take a cross county drive and find it necessary to sleep night after night in the uncomfortable corners of your automobile because no motel will accept you; when you are humiliated day in and day out by nagging signs reading “white” and “colored”; when your first name becomes “nigger,” your middle name becomes “boy” (however old you are) and your last name becomes “John,” and your wife and mother are never given the respected title “Mrs.”; when you are harried by day and haunted by night by the fact that you are a Negro, living constantly at tiptoe stance, never quite knowing what to expect next, and are plagued with inner fears and outer resentments; when you are forever fighting a degenerating sense of “nobodiness”–then you will understand why we find it difficult to wait. There comes a time when the cup of endurance runs over, and men are no longer willing to be plunged into the abyss of despair. I hope, sirs, you can understand our legitimate and unavoidable impatience.

He puts a number on it, to show that people have waited long enough for justice: 340 years, which hearkens back to the founding of the European colonies at Jamestown and Plymouth: in other words, the very beginning of what the US claims as its history as a nation. It has always been like this here. He makes a comparison between countries the US considers both less developed, and less dedicated to the ideals of freedom and equality, the nations in the “Third World” that were at this time throwing off their colonizers and beginning to build new nations, with varying degrees of success — but all with a faster pace of change than the US, for all of our vaunted modern innovative, creative spirit and love of freedom, and he uses a fantastic metaphor to show how sad and simple this all is, that African-Americans have to fight this hard just to get a goddamn cup of goddamn coffee (Cusswords added for emphasis, because Dr. King was much too polite to say it himself).

And then Dr. King writes what may be the best sentence I’ve ever read.

Do you see that? It’s all one sentence, from after “Perhaps it is easy for those who have never felt the stinging darts of segregation to say, “Wait.” up until he says, “then you will understand why we find it difficult to wait.” He uses full sentences inside it, when he quotes his son asking why white people are so mean; but it’s still only one sentence. 316 words.

And it’s unbelievable: everything in it, from the way he describes the different experiences of African-Americans in the US, to the way he starts with the most active and deadliest threats, and then ends with the most personally and emotionally troubling and dehumanizing, going through all the different ways one is affected, in every single aspect of one’s life, through all of one’s identities, not only as a civil rights leader and a member of an oppressed people, but also as a husband, as a father, and as a man; everything he does in this sentence is amazing. The way he uses the second person “you” to include his — mostly White — audience, so that maybe the White people can understand some of what King and every other African-American understands, and uses “father,” “mother,” “brother,” “sister,” and every other family relationship to show that everyone, every human, are our brothers and sisters, our family. The way he names lynching and murder, and equates violent mobs with policemen, as both groups have savagely brutalized African-Americans in this country. The way he appeals to parents by including not one but two heartbreaking scenes with a father having to explain to his children why they must suffer in an oppressive and unjust society. The incredible metaphor he uses, about the people smothering in an airtight cage of poverty, in the midst of an affluent society: because the airtight cage is a paradox, a cage is only bars, so it should not be able to smother anyone; just as poverty should not be suffocating people in this society: and it in the midst of this society, because affluent people are all around those who are suffering and dying, are watching them die, and doing nothing about it. The cage itself makes this seem like a zoo: an exhibition put on for the amusement of the crowd. The poetic way he uses phrases like “your tongue twisted and your speech stammering,” and then throws the harsh, crude word “n*gger” at us as it has been thrown at him, casually, frequently, like it’s his first name.

The way this periodic sentence — a term for a sentence that has the main clause, the most important subject and verb, closer to the end than the beginning of the sentence — ends with the final statement, “then you will understand why we find it difficult to wait.” Making the audience wait, through 316 words, for that final statement of the sentence’s purpose. Ending with the word “wait,” that same word that set all of this off. With the incredible understatement of “we find it difficult to wait,” through lynching, through drowning, through beating, through suffocating, through the tears of children, through one’s own dehumanization: it would indeed be difficult. But it is cause and effect, if-then: when we have gone through what King and other African-Americans have gone through in this country, then we will understand. And the corollary, of course, that until we have gone through it, we cannot understand it: but at least now we have a description of it.

It’s the most amazing single sentence I know. It’s one of the best arguments I’ve ever read, in a piece that continues after this to build up his argument for another 30 paragraphs, point by point explaining why the actions of the protestors in Birmingham, and King’s movement’s actions more generally, are right and good, and should get the support that the White community denies them. I have never been capable of teaching it fully to my students: I can’t make them understand how remarkable King’s achievement is in this essay, because it’s so far beyond their usual argument that it’s like another language. I doubt I’ve done it justice here today; but I felt like I had to try.

Happy Birthday, sir. And thank you for all that you gave this society.

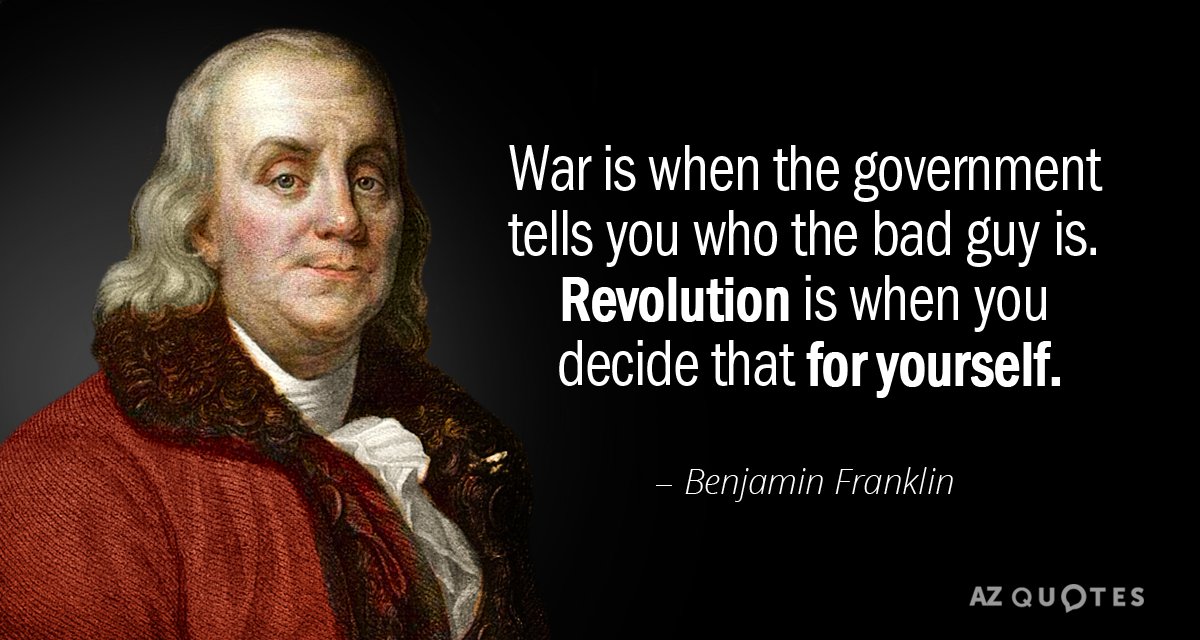

![Image may contain: 3 people, beard, text that says '12:23 Kacey Elise Wheeler Kacey Elise Wheeler Yesterday Extreme Liberty 10:55 This shirt our Scofflaw collection has been really popular lately! Get while it's hot! [Link below] ...See More Those would upliberty purchase alety are bitches. Beajamin Franklin (probablyi Like Comment Share Whoolor ខ'](https://scontent.fphx1-2.fna.fbcdn.net/v/t1.0-9/116118289_3113653262088849_2970895150707464983_n.jpg?_nc_cat=100&_nc_sid=1480c5&_nc_ohc=k59cdIldaTMAX8CHtSa&_nc_ht=scontent.fphx1-2.fna&oh=2af496e3659c3e44e40f962e37528fbf&oe=5F4C81C4)