I work a lot.

My work day runs from 7:45 to 4:20; just about an 8-hour day if I got a half hour for lunch. I don’t, of course; my lunchtime is spent supervising and often talking to students, or else grading and planning. I do sometimes manage about 20-30 minutes for eating and something mindless like scrolling through social media or playing Minesweeper; but as there are almost always students in the room while I’m doing it, it isn’t duty-free: I would still need to intervene if one of them punched another, or if they said something that required action on my part, like “I’m going to cheat on my math test next period” or “I’m going to blow up the school” or “Clearly trickle-down economics are the key to prosperity, and also donuts taste terrible.”

And of course, my work day doesn’t actually end at 4:20. (No comments, please, about how the administration at my school decided to let teachers go PRECISELY at the Smoking Hour; it’s a coincidence of scheduling, not evidence that one of the superintendents is Snoop Dogg. Though that would be badass. “Hell yeah, you can teach that CRT shit, yo. Load them lil homies up wit dat GANGSTA truth, fo shizzle! CRT from tha LBC, and the D-O-Double-G!“) I commute, which certainly should be considered part of the work day; that adds an hour or so total. But even without that, I frequently have meetings and so on which run past 4:20; 5:00 is more accurate at least two days a week. Most teachers go home every night and plan for the next day; I’ve been teaching my classes long enough that I don’t need to do that any more — but I do work on the weekends, every week, for between four and eight hours; sometimes more. It’s the only way I can keep up with the essays I have to assign, and the kind of feedback I want to give on my students’ writing. I also read extensively for my classes: finding new material, refreshing my memory of old material, and so on; all told, my work week is closer to 50 hours than 40, and often beyond that mark.

This is not intended to complain — though I will certainly use this, as all of my fellow teachers do, to rebut the absurd claims of those who hate education and educators and argue that teaching is an easy job because we have summers off: even apart from the truth about teachers in summer time, which is that we are still working on planning and researching and completing professional development, and often working our second jobs required to make ends meet; when teachers work approximately 50 hours a week during the 36-38 week school year, those extra ten hours every week add up to almost 400 extra hours, which is — yup, just about ten weeks of a regular 40-hour-a-week job. Or the length of summer.

But no: my point with this summation of my work schedule is this: if I work something like 50 hours a week, for the 38 weeks of my school year — why is my performance evaluation based on one or two formal observations, which total less than two hours’ worth of watching me teach?

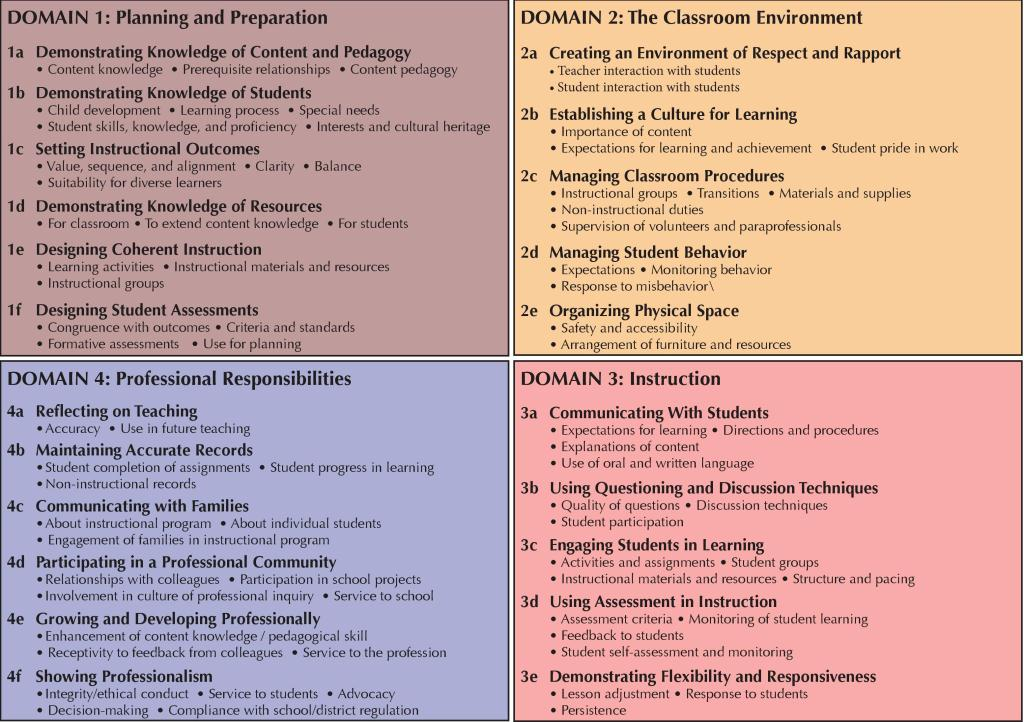

The observation and evaluation system in education is well-known among teachers and students, and pretty roundly derided as a ridiculous means of assessing a teacher’s ability or worth. First, the criteria for success are unbelievable: my school uses the Charlotte Danielson method. Here it is.

Most formal observations are planned and scheduled, which means, as we all could guess and teachers talk about frequently, that we just trot out the dog-and-pony show for the administrators. (By the way: has anyone ever actually seen a dog and pony show? If you haven’t, watch this. The video quality is pretty choppy and annoying, but the dogs and the pony are very cute.) Stories abound of teachers who feed their students the correct answers to questions before the observation so the students can give all the right answers while the administrators are watching; my favorite is the urban legend of the teacher (Which I know has been actually imitated more than once, but I suspect the original story is apocryphal) who told the students that, when the teacher asked a question, if they knew the answer, they should raise their right hand, and if they didn’t know, they should raise their left; that way the teacher could pick from a sea of raised hands, and every time, the student would give the right answer. Genius.

Whether that clever story is apocryphal or not, the dog-and-pony show definitely is not: I’ve done it myself several times. My very first observation, I tried to work out a complicated group work system called “jigsaw” groups, to show off that I did indeed know how to run a group lesson; unfortunately, several students were absent that day (Maybe because they didn’t want to perform for the admin?) and that screwed up my groups, so the whole lesson bombed; that taught me the folly of trying too hard for an evaluator’s observation. But at my current school, when my administrators had observed me half a dozen times, always telling me I needed more group work and universal student participation — suggesting, every single time, that I both call on students (which I refuse to do, having been a dreamy introvert and therefore understanding how terrible it is to be snapped out of a reverie to suddenly have to admit you don’t know the answer, and frankly I’d rather let them daydream and miss part of the lesson) and use exit tickets (which I don’t refuse to do, but — my God, what a pain in the ass those things are) — I did indeed create a group lesson specifically for the next observation, and ran it when the admin came even though it was out of sequence with what the class was working on every other day that week. And I got my most glowing review to date. And then the next day I went right back to what I had been teaching before the interruption of an observation.

So beyond question, the system of scheduled formal observations does not give good information about what a teacher’s classroom is like on a day-to-day basis. But it’s more than that: even surprise observations, which I’ve had every year for the last eight years I’ve been at my current school, and will have again within the next month or so when observation season starts, don’t give the observers a good idea of what the classroom is like every day: because on a normal day, there aren’t a handful of school administrators looking uncomfortable in student desks during the class. Does anyone imagine that students are unaware of administrators in the room? When these are the people who most frequently enforce school discipline, and impose consequences on the students who break the rules? And there they are, just staring at the students?

Let me ask it this way: when you see a cop car driving down the road near you, do you slow down and make sure you don’t pick up your phone for any reason? Me too. And so with students while an administrator is observing the class: it’s called the Hawthorne Effect, after a study of productivity in a factory called the Hawthorne Works. When management changed conditions for the workers, productivity improved every time, even when the change was to go back to the former conditions. Because the workers knew: when something changed, the bosses were watching. So they worked harder, for a short period of time. I can never get a class to behave nearly as well as any class being observed. Though at the same time, the discussions that are the standard operating procedure in my literature classes are much more stilted and uncomfortable, because normally I and the students both crack jokes all the time, and go off on tangents into different subjects that I or they or both find interesting; none of that stuff happens during an observation — which means the observers get to see precisely what they want, which is an orderly, focused classroom; and not what my class actually is, which is an environment where a whole group of people can feel comfortable sharing ideas and discussing literature.

But even without that, formal observation is a terrible system: because it’s just not enough time. I work hard to ignore the observers when they come in. I actively make jokes and go off on tangents (I didn’t always, please note, but I am now one of the more senior and one of the more respected teachers at my school, and there’s little chance that I’m ever getting fired, and no chance that I’ll ever get fired for incompetence or irreverence during an observation; for God’s sake, I dress up like a pirate every Halloween and teach my classes in my Hector-Barbossa-like pirate accent. Irreverence is a given. Also, I am a highly competent English teacher.) and encourage students who do the same. So while observed lessons are better behaved, still, the discussion actually isn’t all that different; it does in fact give a pretty good view of my regular class, if still an unusually well-behaved one. But the other problem remains: the observers are only seeing one class, on one day. They’re not seeing the procession of students through my room. They’re not seeing how different it is to have a class in the morning versus the afternoon, to have one on a Monday versus a Friday, versus the last day before a vacation, versus a test day, or the day before a test day. They’re not seeing the same class when THAT ONE KID is present, or if they are, they don’t see what a difference it makes when THAT ONE KID is absent. And of course, they’re not seeing the work: they don’t read the essays, don’t look at the quickwrites or the annotations or the graphic organizers. They don’t read the emails apologizing for that bad day I had the other day, Mr. Humphrey, but I promise I’ll do better. They don’t read the emails from parents asking for some leniency because they had a family emergency and their child hasn’t been able to sleep for a week.

They don’t know what I do as a teacher. They can’t see what I do in just a single hour. They can’t see what I do unless they watch ALL of what I do; and of course they can’t do that. There are so many incredibly different elements that go into teaching, so many different skills and tasks that all must be completed for a single effective lesson, as part of a single effective class. There’s just no way to observe it all for every member of a school faculty. And of course, it changes every year, as students change and class dynamics change and class assignments change for teachers, as curriculum changes, as new ideas occur to us and we replace things that didn’t work last time — and so on, so on.

When I worked as a janitor, my performance evaluations were both easy, and fair. There were a set of assigned tasks that had clear outcomes: if I was told to mop the upper corridors, then my boss could go look at the floor and see the job I had done. If the floor was clean, I had done my job; if not, not. My boss was generally at work with me every shift: she could see how long it took me to complete a task, how efficient I was. She could see if I had initiative to take on a different task if I finished my assigned duties, or if I just sat around like a lump. She could hear me interact with my coworkers (Not to mention she herself interacted with me every day, pretty much) and with the clients and the general public, because she was there when I was working, and we were working in pretty much the same place, all the time. Once I’d worked there for two or three years, I was given more independence and responsibility, which meant I worked unsupervised more often; but still, my boss could look at the windows the next day to see if I had actually washed them like I was supposed to. So those performance evaluations were a breeze, and I never felt like they were unfair.

Now? I don’t feel like I could possibly get an evaluation that could be fair. I generally get sterling evaluations: I really am a good teacher, and a popular one, and the school both recognizes that and recognizes that they should probably keep me happy, because it would hurt the school to some extent if I quit. (The school would remain, don’t get me wrong; but here in Arizona, where School Choice is such a strong part of the education environment, you can bet your sweet bippy that some students would leave the school if I did. It’s happened several times in the past when popular and successful teachers have moved on.) But even though the evaluations I get are good, and I get an amount of “merit pay” as a reward for my good ratings, I still get a little offended by the evaluations. Because those people don’t have any idea what I do. Not really. So who the hell are they to judge me?

The irony, of course, is that so much of school these days (And maybe always) is about judgment. Assessment. Evaluation. Accountability. It seems like that’s all anyone in authority can talk about — though my colleagues and I have noticed that they have stopped using a phrase that was all the rage ten or twenty years ago: authentic assessment. Authentic assessment was the idea that some evaluations of a student’s learning would be more genuine and more effective if they were attached to a task that was, first, genuinely part of a class, rather than an externally created and scored standardized test, and second, similar in some way to something the student would actually do with the skill in question: so, for instance, testing a student’s writing ability with a resume and a cover letter seeking a job, if a class has been studying resumes and cover letters, would be an authentic assessment. We don’t talk about that any more. Probably because standardized tests are still the only thing that higher-ups pay attention to, a problem that has only gotten worse in the last decade; but maybe also because they became aware that their own assessment of teachers was anything but authentic, no matter how it had the trappings of authenticity. It seems clear to me, at least, that the idea of having the appearance of authenticity is self-contradictory: and so with formal classroom observations.

I’m talking about this this week for two reasons, even though it doesn’t necessarily fit in with my planned course of investigation and explication of the state of education in the US today; certainly this is a part of the world of education, and inasmuch as observations and evaluations have some impact on teacher retention and so on, this subject isn’t far away from what I’ve been speaking about. But if I had been going straight ahead with my intended subject, this week would have been about school as an entity: the purpose and value of actual schools with actual classrooms where students sit in actual desks, as contrasted by virtual classrooms or homeschooling. Hopefully I’ll take that on next week; unless I find something else that takes my focus, as has happened this week.

The first reason for this semi-tangent is my wife. My wife taught art full-time for three years, and then quit three years ago, because she is first and foremost an artist in her own right (And an incredible one) and teaching full-time took too much time and energy away from her art. But while she was working there, she got observed — by administrators who do not know the first thing about art. They told her, directly, that they hadn’t understood what she had been talking about in class while they observed her — “But the students seem to get it, so good job!” In truth, past administrators who have performed my evaluations haven’t understood my subject terribly well; some of them haven’t even understood teaching in general, and their comments and critiques relied on what they had gleaned from professional development and teaching manuals and so on. Not terribly helpful, but they seemed satisfied when I would nod, say, “Okay, that makes sense, I’ll try to do more of that” — and then go straight back to teaching the way I always have. Because I do understand teaching, and my subject, and because the way I teach is effective. It is not effective with every class and every student: but that’s part of the conversation about schools, which I will come back to next week.

The second reason I wanted to talk about this subject for this post is because this last week, I was observed. Not by my school-level administrators, and not to evaluate my teaching: this time it was district personnel come to check my compliance with the new systems that have been put in place this year. As with every year (And this is the other contender for next week’s subject matter: the way every new year brings new systems and new demands and new policies, and the old ones are sometimes superseded but never simply taken away, until we end up with something like a multi-layer shit sandwich — or perhaps a shit tiramisu would be the better metaphor. I’ll consider.), and despite the last two years being maddeningly difficult and exhausting years because of the pandemic and the quarantines, we have a new system in place, implemented by the district without any consultation with the teachers (and apparently over the objections of school-level administrators, though that is only scuttlebutt), which has to do with the curriculum. Not a change in curriculum: only a change in pacing, and in — you guessed it, if you have any experience working in education — assessment. So two district administrators made the first of what will be several monthly visits to the school, to step into various classrooms and examine how well the teachers are implementing the new system.

And if you have any experience with me and my teaching, you already know what they found: nothing. I’m not complying with the new system, precisely because it doesn’t mandate any change in curriculum; and I’m not going to change my teaching methods unless somebody gives me a good idea. They didn’t. So they saw what every other administrator has seen when they come into my classroom: a discussion — lively, in the case of the class they came into, one of my more active groups — with a fairly intense focus on specific details that show characterization and theme, in a complex piece of literature, in this case the brilliant short story “Valedictorian” by the incredible N.K. Jemisin, a piece I have picked up in the last three years because I’m trying to include more modern writers, more women writers, and more writers of color, and Jemisin is all three in addition to being incredible. And I hope they liked what they saw, even if I’m not in compliance with their system: because if their job is to improve education, then what they saw was reflective of their goal, if not of their methods.

But I don’t really care what they saw: what I care about is what they did. These two men, complete strangers to most of my students (One of them used to work at my school site, but was largely invisible in the lives of students, particularly these students, because they have often been online for the last two years and so don’t know any school personnel other than their teachers, and us only as faces on Zoom until this year, in some cases), came into class, opening the locked room door with a master key, in the middle of said lively discussion. They had emailed me that they were coming (I had warned the students they might come in, but I had no idea what period or what time they might come into my classroom) and told me not to make a fuss, so I didn’t acknowledge them; but I’m sure I did exactly what I saw the students do: they got quiet, they subtly hid away their phones and headphones and so on, and sat up more straight, their eyes darting to the men and away. Passing by the comfortable chair I had set up front in case one of them wanted to sit there, and ignoring my desk chair, which was also open, they went and sat amongst the students: one in an unoccupied student desk, and one standing awkwardly in the corner of the room, right behind a female student who spent the next fifteen minutes deeply uncomfortable with the close presence of a strange man right behind her. They stayed there for a quarter of an hour, saying nothing, while my students gallantly and honorably maintained their composure and actually had a pretty damn good discussion of the story; and then they left. And, I’m sure, promptly invaded another classroom, and made another group of kids vastly uncomfortable.

This is not a good system. If they wanted to see if I am in compliance with their system, they should have asked me. I would have told them I’m not. I might have done it sheepishly and said I would try to comply in the future; but I wouldn’t have pretended to be doing what I’m not. They could have looked at my online records to see whether or not I was completing the tasks they wanted me to; it should be immediately clear that I’m not (To be fair, I’m doing a couple of the things they want. And also, I already achieve what they’re hoping to achieve: one of those same administrators gave me an award at the beginning of this year for my students’ achievement last year. But I’m not in full compliance, and they could know it without even setting foot in my room.). If they wanted to know if I’m writing what they want me to write on my board every day (Standards and objectives in “student-friendly language,” and no, I’m not — that’s another post I’ll write, about the appalling lie that is standards-based education), they could have come in at the end of the day: no teacher on Earth erases the board at the end of the day, except those who then go ahead and fill it up again with the needed information for the next day; if I was writing standards, they’d see one or the other, the past day’s or the next day’s.

All of that evaluation could be done without disturbing my class. Without making my students — and me, but that’s not important — uncomfortable when we should be working, trying to achieve the very thing they are trying to see if we’re achieving. And if they’d stayed away, we could have made more progress towards that goal of actual learning. Not much more progress; they weren’t in there long, and it didn’t mess the discussion up too much — but it did get in the way. It was a problem. And for what? So they could leave some boxes unchecked. If you’re thinking they came back to talk to me later, to let me know I was out of compliance and that was an issue, or to share with me their observations, perhaps even to offer helpful or at least well-meaning advice, well — you’ve never worked in education. School administrators sometimes do that. District and above? Never.

The last reason I’m writing about this, the part that upset me most, was this: the observation made one of my students, as they told me the next day, feel as though they weren’t being treated as a person, but rather just some data point to be measured. It made that student mad, and it should have. And it made me mad, because I have worked very hard to make this student feel as though they belong in my classroom and at this school. And they do. It’s the administrators who don’t. And let me just note: you people put cameras in every classroom, over the objections of the majority of the students and staff. Use them. Observe me through the lens. Stay the hell out of the room unless there’s a problem you’ve come to fix, instead of cause.

One part of my job which I hate, but which I take very seriously, is assessment. My students want to know how they’re doing; the community, everyone from the school administrators to the students’ parents to their future employers and college admissions officers, all want to know how they’re doing. So even though I hate and despise grades and grading, I do it. I do it as well as I know how, and I spend appalling amounts of time doing it. And one thing that is critical to the process is: time. Time, and multiple measures. No one thinks that we can know all about a student’s knowledge or ability or especially their progress based on a single assessment, a single observed moment, no matter how rigorous that assessment may be, no matter how reliable or valid is the data that comes from it. If nothing else, all of the education system these days is focused on growth over time: and of course growth can’t be tested in a single instance, because you need two points to make a line and find the rate of change for that line over time. So I guess it’s good that the administrators are going to come back to observe again — but it’s absurd and terrible that they’re just going to do the same thing over again, with the same problems and flaws and negative consequences of their actions, many of which will invalidate their data. Again.

If I graded my students this way, those same administrators would fire me.

If they had any idea what I was doing.