Bro, Do You Even Read?

I’ve now written about movies over books. It felt false; I had to work too hard to convince myself that movies were actually better than books. I’ve been telling my students for years that they should try arguing from the opposite side, as a way to gain depth to their perspective, to understand their opponent – and therefore defeat him more easily – but I guess I haven’t done it myself, not often enough. I’m not sure if that says something about our society, that we have trouble stepping out of our comfortable ruts and visiting ruts on the other side of the road (which is certainly true) or if it says something about me, about my arrogance, telling people what to do when I never do it myself. It’s probably the second one. I’d like it to be the first.

I wrote, as well, about why books are better than movies; or to be more precise, why people who watch movies but do not read books are destroying our society. It didn’t feel false: I believe that. I’ve read Fahrenheit 451, and I’ve seen how close Ray Bradbury got to what is actually happening in our world; people who don’t read at all, and thereby don’t gain the necessary skills that reading can give, are a genuine threat to us all. They lack imagination, and they lack empathy; but they don’t lack power, or influence, or a voice. And thus are they very dangerous.

But while that essay didn’t feel false, it did make me both angry and sad; and I’d rather not feel that way. So I find myself seeking a middle ground: something that will be true to what I really think, but will also be fair to the other side, and won’t make me feel like I’m pointing fingers at those I damn to perdition, sentencing them to burn at a stake, flames rising from burning books (Because zealots always destroy what they love, along with what they hate) to purify their corruption. Arguing for destruction is no way to accomplish anything but destruction; if I imagine my angry essay becoming influential, all it leads to is a witch hunt for the non-reader, and protestations of devout readerlihood. I would, for the first time, expect the Spanish Inquisition.

So the middle ground is this: I am currently reading a difficult book, Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man. And it’s fascinating, really; it challenges me to find hidden meaning, it makes me think things I’ve never thought before, it gives me insight and inspiration. But it’s hard. I can’t read it for long, especially not after a day of teaching and/or reading essays. So when I get home, in the late afternoon or early evening after I’ve relaxed post-work for an hour or two, I may read it, for an hour.

Then I watch TV. Or play mindless video games, things like Mah Jongg or Candy Crush or Guitar Hero. Then, when it’s time for bed, I read again (because screens disrupt our sleeping patterns) – but then I read Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets. Because it’s relaxing.

I don’t watch very many movies, specifically, but it’s a fool’s game to try to build a distinction between movies and television; television breaks up a story into chapters, or it tells several related stories – a literary model followed by the best-selling novel of all time, Miguel de Cervantes’s Don Quixote. Right now my wife and I are watching Dexter, at a rate of about one episode per night; a single season, twelve episodes, is indistinguishable from a long movie – like, say, The Lord of the Rings, which is nearly twelve hours total in the extended editions, just like a dozen episodes about my favorite serial killer. My wife joins me for the TV show, and then she goes to her studio and draws and paints; she hasn’t read a book in months. She feels guilty about it, and I know that’s because of me and my ire about non-readers; but I don’t consider her a non-reader, just a person with a very difficult and trying job who prefers art as a means of relaxing at the end of the day. How can I criticize that? Is art any less valuable than reading? Of course not.

But how can I let people – specifically my students – think it’s okay to watch movies and TV? Just because I try to find the middle ground, enjoying both books and television, that doesn’t mean that my audience will join me there. I know how it works: when I tell students that the first draft doesn’t have to be complete or polished, you don’t give me something rough; you give me one paragraph that’s mostly typos. When I tell you the book report doesn’t have to cover the entire work, you give me something that only covers three chapters. When you realize I’m lax about deadlines, you simply stop turning things in until I actually give you zeroes and your grade drops. When I say once that grades do matter, everything else I ever say about grades not mattering is gone forever – I confirmed your preferences, your prejudices; now you’re done listening.

You really are good Americans.

So if I say that movies are entertaining, and are important as a source of relaxing entertainment, how do I convince you that you also need to read, to do the work, to make your mind tired before you get to the relaxing part?

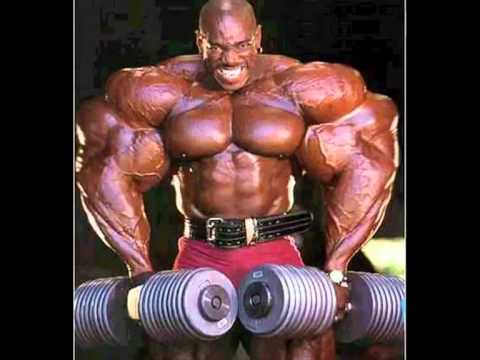

Here goes. Reading is like working out. If you’re really dedicated, if you truly love it or it suits your ambition, then you can do it every single day, for hours at a time – but then mentally you’re the equivalent of this guy:

And nobody wants that.

For most people, who just want to be healthy and happy, you should work out a few times a week, on a regular basis. Read something challenging. Of course it doesn’t have to be a book, specifically, and it doesn’t have to be fiction; it just has to be reading, and it has to be challenging. This is where you strain, and work until you fail; this is where you build strength. Then, on other days, do something like cardio or abs: read something easy, something you could keep reading for a while without hurting yourself. The key there is to keep at it, to not give up.

Once you have done your workout, then it’s time to relax: do something easy, something that doesn’t tax your brain at all; watch a movie, watch a TV show, play a video game (And please don’t tell me that video games are mentally challenging. I play them, too. They’re not. If figuring out how to finish that mission on Grand Theft Auto is mentally challenging, then your brain is out of shape, is a couch potato of the first order. You need to read more.), have a conversation, take a walk, take a nap. Take it easy.

But for the sake of your mind, don’t just skip straight to the nap. Americans already do that with exercise, which is why the nation is unhealthy and out of shape; our brains are moving that way, as well, as we spend more and more of our time taking it easy, and not enough of it working out. You also don’t want your brain to look like this guy:

Moderation is the key. A little of this, a little of that; a little reading, then a little Netflix.

Now: as a student, you get a pass, like my wife does; you are involved in a mentally taxing endeavor, one that takes up all of your time and mental energy. So your free time should be spent relaxing and recovering. Until you reach the point where you aren’t having to work very hard mentally: summer time, or senior year, when you have two academic classes and nine TA/free periods. Then you need to work out. Then you need to read.

It’s important. It’s necessary. And because our society is based on information, which is still transmitted through the written word, then the mental exercise you must master, and then continually practice, is reading. Challenging reading. Depending on what else you want to do with your life, other mental exercises may be necessary for you, as well: math, science, art, engineering, music, what have you. Perhaps making movies will be your mental challenge, and if so, carry on: it is a difficult thing to do well, as shown by the number of people who do it badly. Movies are fun, but they aren’t necessary: except inasmuch as relaxation is necessary. As to the question of whether watching movies is a necessary means of relaxation in our culture, if you must watch certain movies or television shows in order to understand how our culture works and to participate in it, I leave that argument for another day.

Right now, my brain is too tired. What time are those sports games on?