After my last post about my buddy Joe Biden, I was challenged. I was challenged from both sides: by a liberal friend who focused on my point that Biden was the lesser of two evils, and couldn’t get beyond that to my points about how, really, the election of Joe Biden is about preventing actual evil which would result from the election of Donald J. Trump, and that by comparison, Joey B. is not evil at all; and by a conservative friend who pointed out that I was far more forgiving of certain of Biden’s traits than I would be if Trump, who shares many of those traits, were to win the next election. (It is possible that both of these friends would object to my characterization of their objections [and the one for my use of the descriptors “conservative” and “friend”]; if so, I apologize now for what I am about to say regarding both of these positions as I have characterized them. Please feel free to challenge me again, and I may add a third post about this issue — or if you wish, feel free to post a comment directly on this post which expresses your objections to everyone who reads this.)

Regarding the idea that Biden is the lesser of two evils: granted. He is. Does it make any difference if I point out that every single election ever can be characterized as being between the lesser of two evils? That Abraham Lincoln was the lesser of two evils? That George Washington running unopposed was the lesser of two evils, because the other option was the collapse of this particular democratic nation, which would have been a much worse outcome than electing Washington — an appalling elitist snob and a lifelong slave owner who wore dentures made from the teeth of human beings he bought and sold?

What if I point out that every politician is evil in one way or another? That every human is evil? We all have our bad qualities. We all have our wrong-headed opinions. We all make mistakes, and even worse, we all do the wrong thing and do it proudly, and determine to repeat the same wrong action if we are given another chance to do it. All of us.

I understand the desire to have a candidate for president that matches what we really want, that has the right opinions and the right history and the right qualities and the right intentions. I understand the frustration and exhaustion that comes from a lifetime of never getting that candidate. I think it’s the same frustration that comes from never finding the right person to love, especially if one has several failed attempts at finding that person, or if one has the terrible experience of being with entirely the wrong person, and suffering because of it. And as someone who has actually found the right person for me to love for the whole of my life — and who found her early on, when I was only 20 — I can’t blame someone for wanting the same thing that I have. I suspect a lot of people who feel this way about the President are those who feel like they maybe had that person in the past; for a lot of people of a certain generation, it was John Kennedy, and when he was assassinated, Lee Harvey Oswald stole that perfect President from them.

But here’s the thing: John Kennedy wasn’t the perfect president. Neither was Ronald Reagan, or Jimmy Carter, or Barack Obama. Franklin Roosevelt interned hundreds of thousands of Japanese-American citizens. Abraham Lincoln wanted to repatriate the freed slaves to Africa. Bernie Sanders would not be the perfect president: he has a tendency to yell at people, which would not go over well in diplomatic circles. My love is not the perfect love: she is not always easy to live with, as she would be the first to tell you. I am also difficult to live with, as I will be the first to tell you. Nobody is perfect. Every relationship — romantic, Platonic, professional, political — is a compromise. Which means every relationship, always, can be characterized as the lesser of two evils.

Or it can be characterized as the best of all possible options.

There’s a saying which I am particularly fond of: Don’t let perfect be the enemy of good. The intent of the saying is to prevent a bad choice that a number of my students — especially my Honors students, my Gifted and Talented students — tend to make: they work on an assignment, create something they are not very proud of, that they don’t love, and they know they could do better — so they never turn it in. And they get a 0, rather than the less-than-perfect grade they could have gotten if they just turned in the thing they completed but didn’t love, because they would rather have nothing than accept something that is less than perfect: and so they suffer an even worse consequence. They lost the good, because they were only willing to accept the perfect, which then got in the way of the good. We all do this kind of thing all the time: knowing we can’t do something perfectly, we never share what we can do, so we never sing karaoke or bake a dessert treat for the holidays or share that poem or short story. Or that blog about politics: which I frequently stop myself from writing or sharing, because I’m not nearly as smart as the writers I read, as the pundits I pay attention to — so who the hell am I to post my opinions? I’m certainly not perfect, so often, I tell myself I shouldn’t write or post anything at all.

And it’s a mistake. We should do those things, because we can do a good job of them, even if not a perfect job. But the goal of any attempt is not perfection: it is a positive result. You don’t have to hit every note to sound good and entertain the people at the karaoke bar; you don’t have to have perfectly shaped latticework crust on your apple pie for people to enjoy it; you don’t have to have every word just right to be able to communicate your thoughts in a creative way. As I can attest to, and I hope many of you will agree with.

You don’t need to find the perfect person to find love. Just someone who is good for you.

Or, of course, accept that you don’t need someone to love at all, and just love yourself.

For the President, you don’t need to love him, or even like him. You just have to pick one who will do you good. And while Joe Biden could be a lot better than he is, and Bernie Sanders would be better than Biden could ever be, still Biden has done and will do good for this country. I think that’s what this argument against Biden boils down to: we can easily imagine the perfect candidate (though I suspect that when we do so, we are ignoring some aspects of the perfect person which would actually make them less perfect, more human; more evil.), and JRB sure as hell ain’t it. So we don’t want him, because he’s not perfect — some of us would rather have nobody. And I do fully recognize that nobody expects a politician to be perfect; people arguing this position just think Biden isn’t good enough to deserve a vote, no matter how bad they may agree that Trump is. Not that he’s imperfect: it’s that they think Biden sucks. If it isn’t clear, I don’t think that’s true, but if you do think that, then please, feel free not to vote for him; you can always choose to not accept any of the choices you don’t like.

Let me say it as clearly as I can: I am not saying that every individual reading this — including my friend who is sick of choosing the lesser of two evils in every election — needs to vote for Biden. You do not. I think voting third party is an excellent choice. I do think that Robert F. Kennedy Jr. is a vile candidate — much closer to the greatest of three evils than the least — but if that’s the way your vote needs to go, then do it. We should break the two-party duopoly, and voting for a third party candidate is an important step along the way to accomplishing that.

However. If you do choose not to vote for Biden because he is not someone you can support, but you recognize Trump is a serious problem, then I would like to make two requests of you. The first is that you do actually vote. Staying home out of frustration with the system is an emotionally appealing choice, but it does simply lump you into the great ignorant masses who don’t vote for no good reason. The parties, aware that you’re not voting, will consider you “Uninformed” or “Unmotivated,” rather than “Protesting the neverending stream of bullshit we call U.S. politics.” That means they will use their favorite strategy to reach you in the future: advertising. Lots and lots and lots of paid targeted advertising. If you choose not to vote, you are lining yourself up for even more ads in the future, I guarantee it: and that means even more politicians stumping for money, and compromising with the wealthy donors rather than trying to work with voters. Whereas if you show up and vote, and vote for a third party candidate, especially the one closer to the “traditional” party you might otherwise vote for (so if you’re a Democrat, vote for Cornel West or Dr. Jill Stein; if you’re a Republican, vote for the Libertarian or Constitution Party candidate; and if you’re an anti-vax conspiracy theorist who wants to use your family name to shill for corporate lobbyists, vote for RFK. Or actually no: if you’re in that last group, go ahead and skip voting.), you will be one of the voters that trouble them: and their strategic response might be to move closer to that third party in the future, to change their candidates or their policies to ones that you can support. I want that to happen, so if you do vote third party, thank you. Also don’t listen to people (including me in 2016, before I was corrected) who blame you for the outcome of the election. If Biden and the Democrats lose, it will be because of Biden and the Democrats, not because of the people who voted their conscience and picked third party.

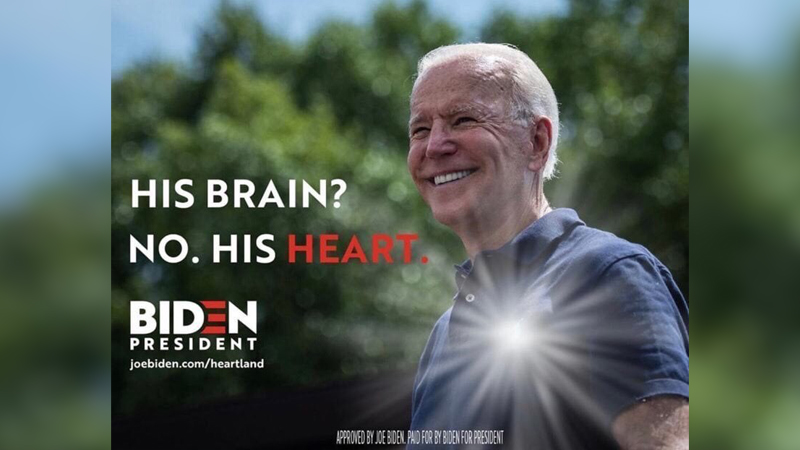

What I want to do here is get people who want to vote for Biden to be excited about that vote. Because it is a good vote. For all the reasons I posted two weeks ago, with the main one being that Joe Biden has far and away the best chance of preventing a second Trump presidency: and that is something we very much need to prevent.

Which brings me to the second thing I would like to ask third party voters to do. Try to do something, other than casting your own vote for Joe Biden, which will help to defeat Donald Trump. If you are willing to vote for Democrats down ticket, do that, and try to help them get elected — because honestly, if Trump won the White House but the Democrats picked up majorities in the House and Senate, I’d almost enjoy watching TFG get stymied at every turn (Almost. Except for the Supreme Court, which will obviously back DJT even to the extent of slow-walking his criminal trial until after the election because they need to hear some absolute bullshit immunity argument. And that’s why I intend to vote for Biden, and encourage you to do the same. Even if he did fail to increase the Supreme Court to 13 members, or to work to impose term limits and ethics requirements on those corrupt assholes.). But if you want to vote third party for President and then vote for Democrats after that (And again, vote your conscience in local and state elections; third parties need to start with the grass roots, and that means getting elected to local school boards and county commissions and so on), that would be great. If you want to volunteer for the Democratic party, to help get other people out to vote for Democrats downticket — especially if you can swallow your ire and let those people vote for Biden, if they want to — then that would be wonderful. And if you can do something to impede Trump: if, for instance, you could find someone like you, too disgusted with the two-party system to vote for either of these shitheads, but who would lean towards voting for Trump because they hate Biden that much, and you could then convince that person to join you in voting third party? Well, you have just taken a vote away from Trump, and you have helped to stop a possible dictator from doing everything he can to tear down this democracy we live in and the rule of law that keeps us all whole and alive. So thank you for that, and for voting your conscience. Those are my two requests, if you can’t vote for Biden but you know that Trump is a danger.

And if you can join me in voting for Biden in November, thank you.

Okay. Now let’s turn to Objector #2, who pointed out, and maintained in the face of my rebuttals, that I had soft-pedalled certain objections to Biden’s qualifications for the presidency, which, he said, were reasonable objections that had been leveled reasonably against Trump as well; and he opined that, if Trump were to win this upcoming election, I would feel much too hypocritical because I would be making the argument that these qualities of Biden’s which I am ignoring or apologizing for now are disqualifying attributes of Donald Trump’s.

Specifically, the arguments that Joe Biden and Donald Trump are old white men who speak badly and suffer from some level of mental deterioration from age.

If I sound dismissive of these arguments, I sort of am. I did not claim that Trump was too old or too white or too bad a speaker or too far down the path of mental decline to be President; I maintain that he is a dangerous narcissistic conman who wants to profit from the destruction of this country as a modern democracy that obeys the rule of law, and who sees racist, sexist, xenophobic fascism as the best means to accomplish that and profit thereby. So I don’t agree that I will feel hypocritical if Trump wins, because I still won’t argue that he is too old and too white and too bad at speaking and too mentally incompetent to be President. I will certainly admit that I might level some insults at that shitbag, because I hate him and everything about him, and in among those insults might be comments about what a dumbass he is or how much of a fumble-mouthed fool he is; but that will be me being shitty to Trump because I hate him, not leveling the same arguments against him which I drew back from in regards to Biden. My criticism of his presidency, if he wins again, will be that he is a dangerous narcissistic conman who wants to profit from the destruction of the rule of law in this country, and sees fascism as a convenient way to achieve that destruction. If there was a young Black woman with a high IQ and a silver tongue running as a dangerous narcisstic conman who wanted to profit from the destruction of the rule of law through the implementation of fascism, I would not support them either. Honest.

But okay, let me address these specific claims. Because I did state that these things are unimportant for Biden, and that may seem inconsistent for me as I have argued in the past that we should have better, younger, and less white leaders, even if I didn’t make those arguments about Trump specifically. In 2020 my first choice was Elizabeth Warren, who I would still vote for if she ran right now; and part of the reason is because she is younger (though not enough younger) than Biden, and smarter and a better speaker, and a woman — though still too white. So how, if I argue that Warren would be better because of her speaking and her mental acuity, can I turn around and say that Biden is a good choice despite his failings in those areas?

For a couple of reasons. First of all, I do not personally believe in the power of identity in politics. For my own self, and what I see as important in a politician, I would happily say “I don’t give a shit who the person is, what race or gender or sexuality or age or any other subgroup they belong to, as long as they do a good job.” The reason I don’t say that is because I understand that the subgroup that someone belongs to is important to millions of people, and I don’t get to tell them how to feel, and because I understand the power of a symbol. Barack Obama did not serve better because of his race: but the fact of his race was important to millions and millions of my fellow citizens, and therefore the fact that he was our only non-white President is important. The thing is, our national politicians need to represent everyone in the country, and so no matter who they are, they need to look beyond their own identity; that includes politicians who are not old white men, because even they need to represent old white men with whom they do not personally identify. Biden won’t do a worse job just because he is an old white man, and if he weren’t an old white man, he wouldn’t do a better job simply because he wasn’t an old white man. Symbolically, he would be LEAGUES better as a candidate if he weren’t an old white man. But anyone who gets the job and does the job well will never get my criticism just for being an old white man.

Donald Trump, on the other hand, wants to make life better for old white men and worse for everyone who is not an old white man. (And actually, inasmuch as he is willing to let his asshole party eliminate Social Security and Medicare, he’s only serving rich white men and not old white men. Biden is largely doing the same because he is indebted to Wall Street and corporate donors. But that also has nothing to do with race and gender on Biden’s part, any more than it has to do with Trump’s identity.) He wants to do that by implementing fascism in order to break down the rule of law in this country, so that he can profit thereby. That is a much bigger problem.

So that’s the first reason: I don’t think identity in and of itself is salient in national politics. I do think socio-economic status is salient, because money insulates people from real life and that does make them less able to empathize with other people, in a way that being old or white or male does not necessarily do; and since Trump has always been insulated by wealth, and Biden has not always been insulated by wealth, I think that’s a mark in Biden’s favor. But he is certainly not in the right place policy-wise when it comes to economics. A good place, but not the right place.

The second reason I will argue that Biden’s qualities are not marks against him as a President is because I have realized, since this whole Trump debacle began, and since I have started learning more about politics and looking back on the Presidents in my lifetime, that a strong single Executive is not in the best interests of the country. The people elected to the post are not reliable. And more to the point, they change at least every eight years, and this country is now so evenly divided that half of the time, that election is likely to reverse the results of the last one — and hand that strong executive power right back over the bad guy. It’s like if Thor defeated the enemy — and then picked them up, handed them Mjolnir, and said, “Here, your turn.”

This is why I argued in my last post that Biden’s general weakness would actually be a benefit, as it would force him to surround himself with good people who would help him do a better job than he can do on his own; I think we are largely seeing that, and seeing the benefit of it compared to Trump’s administration. Trump tended to fire everyone who pissed him off, and then he was left with not enough people to do the work of government; this worked just fine for him because he wants to break government, which will then prove his case that government doesn’t work — a fine and long-established conservative strategy. Biden, however, not looking to do everything himself, but rather trying to show that government can do important work to help people, has done plenty to strengthen the federal bureaucracy, and the result has been a more efficient government that has managed to get more shit done to help people: and that’s a good thing — and it is a result of Biden being willing to delegate authority and work with other people, which Trump is not.

A simple example of this is student loan forgiveness. Biden tried to do it all on his own through executive order, and he was stopped by the Supreme Court. That pissed me off because student loans should be forgiven, and I would love to just see it done with the stroke of a pen; but also, because I do believe more in the rule of law than in student loan forgiveness, I can see the point that Biden’s argument for how he wanted to do it was flawed. I will also argue that the Supreme Court never should have heard the case because the determination of standing on behalf of the plaintiffs was fucking nonsense — “You shouldn’t get your student loans forgiven because I can’t get mine forgiven” is a neener-neener argument, not a real one — but I recognize, again, that some Court cases don’t come from good standing, because the Justices want to put their foot down for one reason or another. I can accept that. So I can accept Biden’s initial plan being struck down as part of the rule of law, and therefore a successful action by government, to stop Biden from taking too much executive power, even if he was in fact doing the right thing and we’d be better off if he had been able to do it.

But Biden then went ahead and started finding small ways, legal ways, acceptable ways, that he could forgive student loans. And it’s slower, and it’s not enough, and that leaves a lot of people out in the cold — but it’s progress.

And because I don’t want a dictator, I am more willing to accept slow progress through compromise within the rule of law than I am fast action by a strongman.

Did I always feel this way? Of course not. When I was a kid, I read Piers Anthony’s series Bio of a Space Tyrant, about a charismatic man who becomes the dictator of a planetary nation-state, and who imposes his will — all for the good of the people. He’s a benevolent dictator, and when I was young, I thought he was both cool and brilliant, and I thought his system was the right one. But see, then I grew up and stuff? And realized that democracy, while it is impossibly frustrating and also slow, and requires compromise with awful people, which then causes harm to good people — is also the best system of government possible, because it disseminates and dilutes power. And power corrupts. (I kinda want to go back and re-read the series now, because I wonder if Anthony’s intent was to show that power corrupts, and that his character was actually an anti-hero like Paul Atreides from Dune — or if Anthony was just playing out his personal fantasies of godlike power and authority, all for the good of the nation, of course. Since he named his character Hope Hubris, I think it was probably the former. But also, Hope gets laid a lot, like a lot a lot; so it might be the latter. Anyway.)

Also let me just say, out loud, that anarchy would be better than any government at all. But as long as we believe we need government, we do need it; and we should have a democratic government. You want to talk about actually eliminating government, I’m interested in chatting about it.

So okay. I realized that Barack Obama, for all of his charisma and intelligence, was an ineffective president — unless you happen to be a Wall Street banker/trader/mogul, in which case he did wonders for you. (It said a lot to me when I found out that Obama had trouble with Mitch McConnell because Obama wanted to argue and debate issues on the merits, and McConnell just wanted to cut a political deal. I hate that McConnell’s stance is more realistic, because I relate to Obama’s desire to convince the other side of his rightness with every ounce of my soul; but I get that McConnell’s stance is more realistic. This is also when I realized for sure that I would be an awful politician.) I realized that Biden, for all of his stupid-ass gaffes and his inability to give a good speech, has done more for the 99% in four years than Obama ever did in eight — and more than that charming amoral shitbag Clinton did in eight, too. I realized, as I’ve said, that a stronger executive, while it does potentially achieve more of my goals because it means someone can actually implement progressive ideas over the objections of Congress and the courts, is bad for democracy, even if those ideas are good — because I’ve watched Trump do shit that he shouldn’t have gotten away with, but he was able to because past Presidents created an atmosphere where he could do it. Like using executive orders to incarcerate migrants, for instance.

Which Barack Obama did as well.

So: the fact that Biden is a weak leader? Not a terrible thing. It would be great if he was a better, stronger, smarter man — IF he also had the right ideas. And he doesn’t have enough of them, and that’s a problem; but since he doesn’t have all the right ideas, it makes it better that he’s not strong enough to implement all of his bad ideas over the objections of everyone else in the government.

The real problem in his weakness is how he deals with strongmen, which is — not well. He has been incapable of suppressing Putin or Xi Jinping, he has not been able to handle Iran, and he has given bombs to Bibi Netanyahu. I don’t know how many of those things could have been different if he had been stronger, but I do see his personal weakness as an issue with all of that.

But also? Trump would be actively worse in every single way, and we all know it.

Okay, my friend who raised this objection doesn’t seem to know it, as he said that he doesn’t see much difference between Biden’s foreign policy and Trump’s; but that’s whataboutism, and it’s nonsense –same as when he also tried to equate Biden lying about his past (Specifically this: “He lied about his attendance in a black church as an adolescent in Delaware, his work for desegregation, and his role in the civil rights movement? He has simultaneously claimed to have, and to not have marched.”) with Trump’s lies. Trump lied about winning the 2020 election, which he lost; and his continued attempts to maintain his lie about that election have severely damaged this nation in a way that Biden making himself look better than he actually is never, ever will. The two are not the same. Trump would, so far as we can tell, actively support Putin, and Netanyahu, and also obviously Viktor Orban, and Kim Jong Un, and probably several other authoritarians; because that’s who he wants to be. Because Trump is a narcisstic conman who wants to profit from the destruction of the rule of law through the implementation of fascism.

I don’t give a shit that he’s an old white man. If that means a younger, past version of me would be upset by my failure to maintain the party line regarding race and gender and age, sure, that’s fine. I’ll own that. And I would still like to see someone younger, less male, and less white running the country, because I believe in the power of symbols; I would even more like to see anyone at all in power actually doing everything that should be done to help people who are not white, not male, not old — and not wealthy, most of all.

Biden is doing more of that than Trump ever would.

So Joe Biden has my vote. And, I hope, yours too.