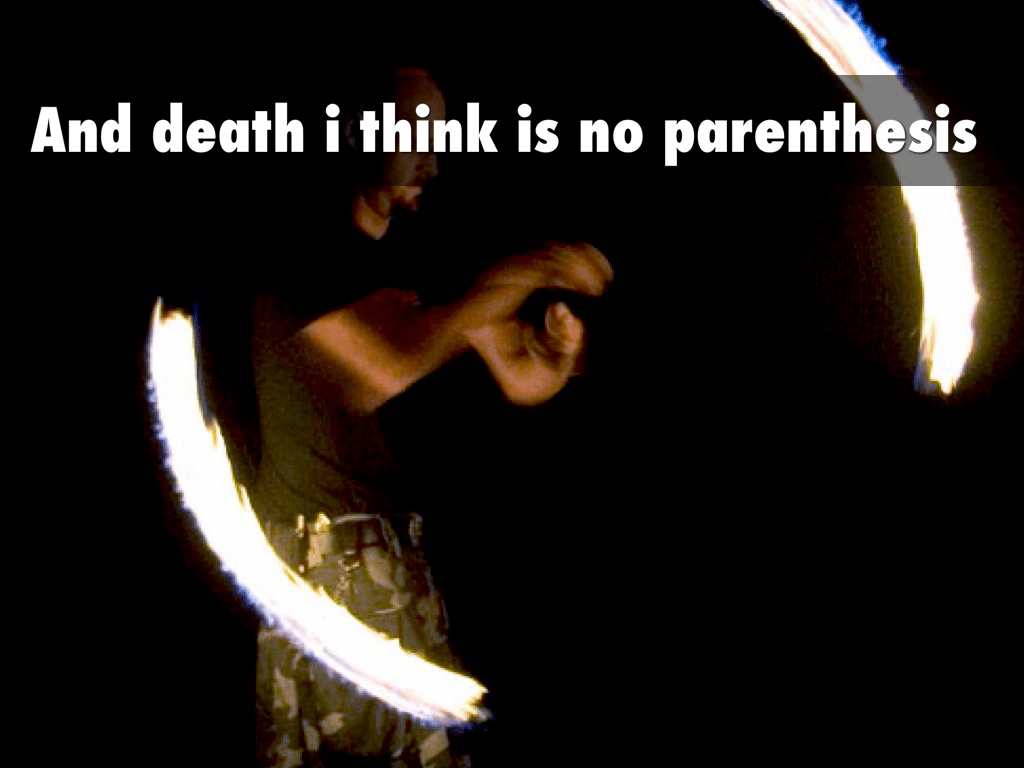

for life’s not a paragraph

And death i think is no parenthesis

One of the difficult things about teaching English is the number of bad ideas that students have about the rules of writing.

And one of the things I find most upsetting about teaching English is the number of bad ideas that students have about the rules of writing which they learned from past English teachers. For instance: one should never start a sentence with “and” or “but.” One should never use the pronoun “I” in a formal essay, one should only refer obliquely to one’s self, preferably in the third person. One should use transitions for every paragraph in an essay, because they help the flow; and one cannot go wrong with the transitions “First,” “Second,” “Third,” and “In conclusion.” And, of course, every essay should be five paragraphs, and every paragraph should consist of at least five sentences, and every sentence should be at least — but actually, I don’t know what the drones tell students the proper minimum length for a sentence is; I would guess about 10 words. Also one should never use fragments or run-ons.

Ridiculous. All of it.

There are no rules.

One of my favorite days as an AP teacher is when I mention to my new students that they can now ignore these rules, for the rest of their writing lives, and that, in fact, if they should never use “In conclusion” again, nor limit themselves to five paragraphs as a structure for an essay, they will make me very happy. The relief is palpable — and sad. We constrain young writers so much: and it helps to crush their creativity and desire to use words, and that is an awful thing to do both to young people and to this language.

There are, I think, two reasons why teachers present these rules to their students as rules; and one of them is understandable, if not valid. The bad reason, the invalid one that is not understandable, is that teachers were taught these things themselves as rules, and they were never allowed to deviate from them, and so now these things are unbreakable rules: sacred cows, taboos never to be questioned, just like the prohibition on the use of the word “Fuck” (And all I really have to say about that is this). I was taught at least some of those things, too — though to be honest, I don’t remember learning them, so either I had genuinely good English teachers, or I spaced out at just the right time and never heard or cared about these rules — but come on. We grow up. We learn to think for ourselves. We see countless sentences that begin with “and” or “but.” We read countless pieces by authors who use “I” in even the most formal of essays. We stop counting words and sentences and paragraphs, and just — read. (I confess I still count pages. This, too, is a bad habit; but if we’re at the page-counting stage, at least the work is long enough that word counts and sentence counts and paragraph counts become moot.) WE FUCKING USE THE WORD “FUCK” WHEN IT IS APPROPRIATE: and we recognize that there are, in fact, many times, many times, when it is appropriate.

So why don’t teachers teach their students that all of these things are bad rules? For one (And damn me, I first wrote this sentence starting with “Well,” and I HATE when my students do that, answer their own rhetorical question starting with “Well.” I caught it, though. Also, that’s not a rule.), teachers do not always question authority. Teachers come from all groups and kinds and flavors of people, but the majority are those who loved school, who were the top students, and who want to pass those wonderful learning experiences on to other people; those people never challenged a teacher in their lives, they were the ones who argued back against the students who did challenge the teacher, the ones who said “Shut up, he’s the teacher, don’t argue with him!” in class when someone else said “That doesn’t seem like the best way to do that.” And then they become teachers, and they don’t want to be questioned by students — who, to be fair, are completely freaking annoying when they argue, because they are used to having their points of view denied, their arguments summarily contradicted, usually by adults who say “Because I said so, that’s why,” or some permutation of that (Like “Because I’m the teacher, so don’t argue with me.”), and so all they have left is making one irritating point and getting a reaction from the authorities who squash them into molds, every single day. But this all means that when an English teacher says that a paragraph has to have a minimum of five sentences, and a student asks, “Why five?” The teacher wants to respond with “BECAUSE I TOLD YOU SO AND I’M THE TEACHER AND MY TEACHER TOLD ME SO WHICH MEANS IT IS A TEACHER’S RULE SQUARED!”

I am not one of those teachers. I did not like school. I questioned authority as a teenager (and I was annoying about it) and I continue to do so now, three full decades out of my teens. So I expect my authority to be questioned; in fact, I invite it. I never say “Because I’m the teacher, that’s why.” (Though I do jokingly argue with students who question my spelling, “How dare you question your English teacher on spelling?!?”) So when I tell students that an essay needs to be longer, or that a sentence is incomplete, and they question me, I tell them why. But then, I’m weird; I like arguing. I like explaining. I like helping people understand why something needs to be changed, why it is incorrect. I think doing that makes the world more comprehensible, and therefore more manageable. I think making the world more manageable for my students is my job, a lot more than making them write five-paragraph essays.

The more understandable reason why teachers don’t tell students that these foolish rules for writing are not ironclad is more to do with arguments. Students like asking “Why?” Not always because they want an answer, either; but because they want to catch the teacher looking foolish, and they love to waste time and thereby avoid work. Sometimes, then, when they get the real answer, they’re not ready for it; so they don’t understand it, because they weren’t really listening — they asked the question only to make the teacher talk instead of assigning work, so when a teacher answers their question, the only response is “Huh?” So when you present one of these writing rules as they should be presented, as something that is entirely dependent on context and writing intention; that, for instance, the use of the word “fuck” in a formal essay, though not entirely forbidden (If you are quoting a character in a Martin Scorsese film, for instance, you have probably a 90% chance that any given quote will include “fuck,” and any form of censoring the word has a poor effect on the serious treatment of the film because it makes you seem too prudish to deal seriously with a movie that has profanity in it) does tend to contradict the tone of a serious essay, and is therefore jarring for the audience to come across in a context that doesn’t require the word be used; then you are going to get argument. Or stupid questions. Mostly stupid questions. (“Can we say it in class? Can I say it right now? Can I change my name to Fuckface McGee, and then you have to call me Fuckface all the time? Would you still say “fuck” if the principal was in the room?”)

So teachers, who deal with enough stupid questions as it is (And yes, by the way, there are stupid questions — see above), will often state an ambiguity as though it were in fact ironclad, just so they don’t have to argue with students. And since the argument won’t bear weight for the thing it is, we have to rely on even more annoying arguments which do have the advantage of shutting down debate: namely, “Because I’m the teacher and I said so.”

This is why, when I was in 3rd grade, the teacher told me that you could not take a larger number away from a smaller number, that 3-7=x didn’t make sense. Not because that was true, but because the teacher didn’t want to explain negative numbers to me right then. The same reason my mother, when I was 4 or so, told me, when I asked where babies came from and where specifically I had come from, that half of me was in my father and half of me was in her. And I assumed that meant that the bottom half of my body was inside one of them and the top half was in the other and they sort of stuck me together like a Gumby figurine (Don’t get that reference, kid? Look it up.), but also, the answer shut me up at the time, which was my mother’s goal.

I understand how annoying students are, so I understand teachers giving guidelines for good writing (It is a good idea to avoid saying “I” in formal essays for two reasons: first because talking about yourself personally is a way to connect emotionally with your audience, which is informal communication, not formal; and secondly because most of our desire as writers to use “I” is in phrases like “I think” and “I believe,” which we are tempted to use in arguments and statements of truth so that we don’t seem too arrogant, and so that we don’t seem dumb if we should be wrong. It’s safer to say “I think Martin Scorsese’s films say ‘fuck’ too often,” than it is to say, boldly, “Martin Scorsese’s films say ‘fuck’ too often.”) as if they were ironclad rules. It’s just that teaching these things as rules takes away all the nuance, all the flavor, from writing; it makes writing boring, which makes students not want to do it. It’s better to tell the truth, and deal with the consequences: there are no rules in writing that cannot be broken, it’s just a matter of what is the best use of language in a specific context.

And no, Jimmy, that doesn’t mean you can say “fuck” in your essay about Sacagawea.

So this went on much longer than I meant it to: this was meant only as an illustrative example, not as the heart of the essay. I really just wanted to talk about how we try to apply rules when there aren’t any rules, and shouldn’t be any rules, and that that is a problem. My main point wasn’t even about English: it was about life. Where there also aren’t any ironclad rules. That’s why I quoted the poem to start:

since feeling is first

by ee cummings

since feeling is first

who pays any attention

to the syntax of things

will never wholly kiss you;wholly to be a fool

while Spring is in the worldmy blood approves,

and kisses are a better fate

than wisdom

lady i swear by all flowers. Don’t cry

—the best gesture of my brain is less than

your eyelids’ flutter which sayswe are for each other: then

laugh, leaning back in my arms

for life’s not a paragraphAnd death i think is no parenthesis

I love that poem. I did a podcast episode on it if you are interested in the whole breakdown of what it’s about and what cummings meant to say in this; but for now, I just want to focus on his first stanza and his last two lines — sort of his introduction and conclusion, one might say. (Though please note he does not use transitions between his — err — paragraphs. Especially not “in conclusion” before the last one.)

So the first stanza: since feeling is first, he starts with, which means either that feelings occur first, before thoughts or actions or understanding or anything else, or else that feelings are more important than anything else, probably with both thoughts connected; but clearly, feeling is better: because he who pays attention to the syntax of things will never wholly kiss you. I love that, because “syntax” is such a nerdy English writing/grammar thing to talk about; it means the way things are organized to create meaning (words, specifically, but you can have a syntax of almost anything that is organized to create meaning), so word order in sentences and sentence order in paragraphs, and aspects like word length and the use ofpunctuation and so on; all of that is syntax. For the lines about the syntax of things and kissing, I think specifically of this scene from the movie Hitch, where Will Smith’s character tries to teach Kevin James’s character how to kiss: but in this scene, it’s not only about the syntax of kissing and of relationships, but it’s about math: and so though Smith tries to get James to think about the passion of the moment, he focuses so hard on the proper methodology that he does not show any passion at all — and then he loses control and flubs it.

The point is, there are not rules to kissing, and there is not math. And the more you think about rules and math and methodology for kissing, the less you are focusing on what you are feeling for the person you are kissing: and that means you are not kissing wholly. Because feeling is first.

So with that in mind, let’s talk about the last two lines, and what I originally set down to write about today.

for life’s not a paragraph

And death i think is no parenthesis

I love this because it can mean a bunch of different things, and that’s what I like best about poetry: in order to distill the language down to its absolute minimum, just the essence, poets take out much of what is usually there to provide meaning to the audience; this leaves the audience having to fill in gaps, make guesses — bring their own understanding to the conversation. Because of that, poetry does a better job, in my mind, of presenting what literature is supposed to be: a conversation, not a monologue. An author is talking about things they have observed or experienced or imagined, and the audience is listening and then agreeing or disagreeing — and adding to what the author says. A poet leaves more silence for the audience to speak, so though the poet may say the same thing in every conversation, the audience always has something new and different to say — and so one monologue can turn into almost infinite dialogues. I love that.

(And because I am pedantic and wordy, I don’t write poetry, I write novels. Heh.)

But because these last two lines use the names of two syntactical structures — paragraph and parenthesis — these two lines connect to the opening stanza: it is telling us that there is no clear structure to a life, and there is not a simple punctuation mark at the end of life that tells us exactly how a life is to be thought of — and maybe my favorite idea present here when I read this is the idea that death makes life silent, makes it unimportant, like a parenthesis makes the words that it contains, turning them from a main thought into supplemental but unnecessary additions. We treat death too often like it is the most important factor in a person’s life. It is not. The life that precedes it is far more important than death.

But in either case, life is not a paragraph: it does not have a definite way that it is supposed to go, with a topic sentence to start (After a transition, of course), and then an illustration of the topic, and then two (or more) pieces of evidence or commentary on that topic, followed by a concluding sentence that shows the meaning or importance of this topic in the broader theme.

And then a parenthesis.

We think this way about life far too often. What actually set this whole discussion in motion for me was a conversation I had with my wife, in which she was railing against people who made decisions about how old other people should be to act certain ways, and how people should act based on what is appropriate for their age.

I am certain you have all had these conversations. Most if not all of you have also made these prescriptions for other people, and probably for yourselves as well. Right? I mean, we all know it: we know that 8-year-olds are too young for R-rated movies with sexual content, and we know that 11-year-olds are too young to drive — and teenagers are mostly too old for dolls and stuffed animals.

We know that 17 is too young to get married and have children, and that 50 is too old for those things. We know that 18 is old enough to make decisions for yourself, and 25 is when everything starts to go downhill. 40 is too old to buy a new sports car, because then it’s nothing but a midlife crisis; and the same with a second marriage to a younger person. And while we’re on that: 5 years is too much of an age difference when you are under 20, and 10 years is too much of an age difference when you are under 40, and two months is too much of an age difference when one of you is under 18 and the other is over 18 BECAUSE THEN THAT OLDER ONE IS A SEXUAL PREDATOR AND A PEDO AND SHOULD BE CASTRATED AND THEN FED TO WOLVES.

That last one is challenging: because I don’t mean to disagree that people under the age of consent should not have relationships with people who are older and may be taking advantage of them. But I do want to point out that the idea that the second someone hits 18 they are capable of taking care of themselves, and the second before that they are not, is absurd.

This goes for all of this. There are certainly stages of life and development, and some of them are appropriate for some things and some are not; I do not think that teenagers should be running the country. I know lots of teenagers. They would not be good at the job. But also, the idea that octogenarians are exactly the right people to be running the country is not more reasonable, based on my experience of octogenarians. Especially those running the country right now (and the septuagenarians who want to run the country right now. Not better.) But at the same time, almost every stereotype and bias we have based on age is belied by not just one exception, but by a whole slew of them. Ten years is a big age difference for a romantic relationship, especially in one’s 20s — except my wife and I met when I was 20 and she was just about to turn 30, and we’ve been together now for the same 29 years that she had lived before she met me. I think it’s worked out pretty well. My father and his wife had a ten-year age difference, but since they met when he was 50 and she was 40 (or thereabouts), and since the man was the older one, nobody thought anything of it. And then, although everyone assumed that she would take care of my father at the end of his life, that went exactly the other way, and he was her caretaker until she passed this last February.

Now my dad is 82, and alone. Should he find someone else to love? Or at least have a partnership with, if not a romantic connection? Or is there not enough time left for him to enjoy a relationship? Would it be too much of a burden for him to put on somebody else, to love him for only the few years he has left? Would it be inappropriate for him to date? To date someone younger? Someone older? How much older? How much younger? How much life left is enough to fall in love?

It this is too much of a dark theme, let me ask a few others ones: should my dad have a sports car? Should he have a fun car, like a bright orange VW bug? Should he get a pet, if he wants one? Should he wear a bathing suit in public? Should he dye his hair, if he wants to? Get a tattoo, or a piercing? Or is he too old for that now?

It struck me in thinking about this that we make exactly the same decisions about the very young and the very old: just as most people would see my dad, at 82, as being too old for a fast car or a fast woman, or a new career or a new hobby or a style change that included something hip and modern, so people would think the same about, say, a ten-year-old: that a ten-year-old should not be in a romantic relationship (I agree with that one) and should not have a car (Less certain on that one) and should not have a career path picked out (Don’t agree with that one: if a kid knows that young what they want to do, then mazel tov: my wife knew she wanted to be an artist before she was ten) and should not get their hair dyed or their body pierced (Other than the earlobes, which apparently are fine for stabbing — hey, does that mean a child could get their earlobes tattooed? Or is that shocking and inappropriate?) or wear makeup, or wear clothing that is hip and modern and stylish.

The way we bracket our lives, with the greatest constraints on the young and the old, turn those two stages of life, the beginning and the end, into — parentheses. We freeze both those times in our lives into immovable requirements: just like kids can’t wear makeup, and can’t possibly make decisions about their sexuality or their gender identity, women must get their hair cut short when they are older, and men have to start playing golf, and men and women both have to retire and may not begin a new job. Kids have to be cheerful and energetic, and old people have to be slow-moving and cranky. And anyone who doesn’t follow these rules, these iron-clad, unquestionable sacred cows, these taboos that are never allowed to change without disapproving frowns and pearl-clutching gasps, is deemed not only unusual or eccentric: but wrong. The butt of jokes, the target of angry stares and social ostracism. Because those are the rules: don’t question society, just do what you’re told.

But no. Because there are no rules. Look at ee cummings’s poem: there are no rules. None that he follows. And yet: it makes sense, even more sense than what most of us write, even though we may follow the rules in order to make our words make sense. The fact that some people are better off following the supposed rules doesn’t mean those rules have to make sense in that way for everyone. Like I said, there are certainly stages of life and development, and children should not be romantic and should not be required to be responsible and adult before they are ready to be; but beyond the most obvious age distinctions around puberty and adolescence, there is no rule that actually encompasses everyone. And there shouldn’t be. Some kids can handle driving a car. Some could write books or create musical masterpieces. Some can know just what they want to do with their lives. Some can wear makeup and have pierced ears, and make it look stylish and cool. And just the same, while older folk are physically more frail and should take that into consideration when picking new extreme sport hobbies (And let me note: kids should be careful about extreme sports, too — because they are also frail, or at least small and fragile.), there too, there are no rules that encompass everyone. If Tony Hawk gets on a skateboard when he’s 80 (if he lives that long — and let’s hope so, because he’s one of those people who is awesome on the Betty White end of the scale) then I’ll watch him drop into the halfpipe, and cheer when he pulls off a trick. Because he could: and even if he can’t, I’d be happy to let him try, if that’s what he wants to do. It’s his choice. It’s all of our individual choices, and none of society’s business as long as other people aren’t getting hurt. Sure, Tony Hawk at 80 would be in danger of hurting himself on the skateboard: but do you know how often he has hurt himself on a skateboard while he has been young? And then adult? And then middle aged? Right. We let him do it. Because it’s his choice. People should be allowed to do what they want, without the weight of social disapprobation because of their calendar age. It’s stupid.

Feeling is first. Life is not a paragraph.

Death is not a parenthesis.