A friend of mine posted this:

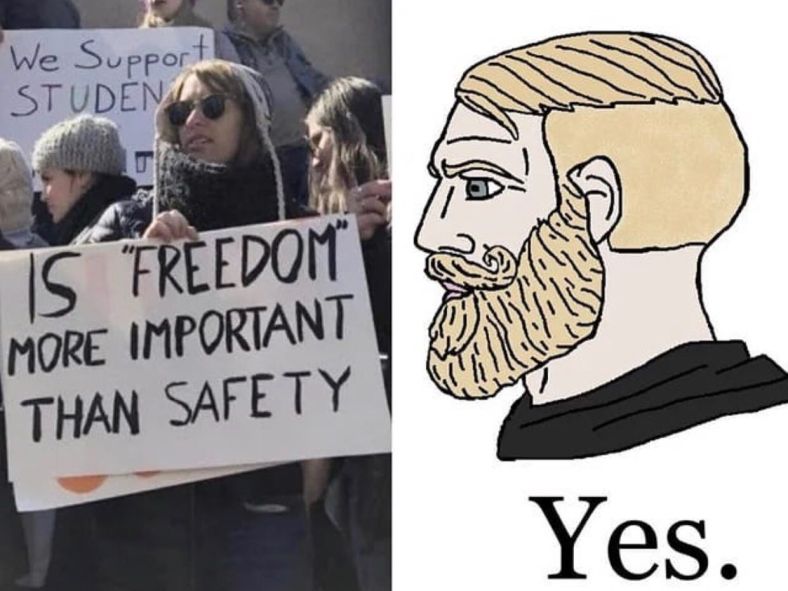

And so, because this is what I do, I asked: why? Why is freedom more important than safety?

He couldn’t answer.

He replied that freedom was the very fabric that the U.S. was drawn on, which is a lovely statement of sentiment — but not an answer. That tells me why freedom might be so important to Americans, if we accept that freedom is indeed what the U.S. was drawn on; but it doesn’t say either why that is the foundational principle of this country, nor why that foundational principle (or this country) are especially important — nor does it answer my first question, about why freedom is more important than safety. (Heh — I just wrote “freedom is more important than slavery.” Not only pretty close to a tautology, but also a pretty good indicator that my subconscious is damned libertarian, if it equates safety with slavery. Actually, I was just listening to the 1619 Project podcast about the foundations of this country, and I have an argument against freedom being the fabric this nation was drawn on. But that’s another subject for another time.)

Understand that this is a good guy, a really good guy. A generous plenty of his posts are focused on telling his friends that he loves them, especially his male friends, explicitly using the word “love” and supporting them in every way he can; sharing his own struggles with depression and alienation; telling anyone and everyone that he is always willing to listen. Basically he is an antidote to toxic masculinity. He is masculine antitoxin. (Also hilarious. Also a frequent and fully self-aware shitposter. Also a boogaloo boi: his second response to my questioning was a citation of the Second Amendment as the only necessary source of safety. People are complex, aren’t they?) He wasn’t attacking me, calling me a coward or a libtard; he wasn’t even treating me as a troll commenter, which would be an understandable response to my asking philosophical questions on a meme. He was really trying to answer my question, and in so doing, revealing at least some of his ideals, if not his explicated arguments for his ideals.

And I don’t think they’re bad ideals. I think this country should be drawn on the fabric of freedom; and though I don’t agree with The Libertarian Cartoon Head (And I find it kind of hilarious and very telling that it is so very Nordic and square-jawed, with furrowed brow and shaped beard and curled ‘stache, blond hair and blue eyes), I also don’t agree with the woman with the sign. (I will give her slightly more credit in her argument because she put “freedom” in sarcastoquotes, which implies that the debate is set on false premises as these debates often are and maybe have to be by definition; but also, I have no idea where this picture is from or if it is even real, so I can’t say if she knows how to use sarcastoquotes or meant those for emphasis, or if she ever really held that sign in the image, or if it was Photoshopped. So.)

Let me tell you what I think: I think both safety and liberty are, quite simply, vital. They are necessary. Both. I’ll actually throw in the pursuit of happiness, too: all vital to our continued existence as thinking, feeling individuals. That’s why they are unalienable rights.

There’s a deeper and harder conversation about what rights are and where they come from, and what it means to have them, which I am not qualified to have; I have a lot more reading to do in the philosophy world before I can take that on. But for this conversation, the layman’s understanding of rights should be just fine.

A right is what you have simply by virtue of being an individual, a specific human being: a person. Your rights are essentially a list of what is required for you to experience and explore that existence as a person, as an entity with reason and free will. You must have life, because if you’re dead, you can’t experience your existence as a person. You must have liberty, because liberty is essentially the opportunity to have your own thoughts and feelings, to express your own thoughts and feelings, and to act on your own decisions, which are based on your own thoughts and feelings. Without liberty of thought, of speech, and of action, you are not able to explore and experience your existence as a unique individual. It’s pointless to say you have reason if you are not allowed to think your own thoughts, and then express what you think (Because freedom that is only locked inside your head is not freedom: a human being is capable of expressing and communicating their thoughts, and that expression and communication of thoughts is a fundamental part of being a human; you cannot be a human if you can only think but never speak your truth.); it is untrue to say you have free will if you cannot act according to that will.

You must have life to be you, and so you have the right to life; you must have liberty to truly be you, and so you have the right to liberty. Either without the other is meaningless and empty. The pursuit of happiness, the third unalienable right listed in the Declaration of Independence, is the realization of these two rights extended forward in time: if I have life and liberty right now, I can be myself; and if I can be assured that I will still have life and liberty tomorrow, I can begin planning and acting with that understanding in mind, seeking most likely to achieve a greater happiness for myself according to my wishes. Also necessary, I would argue — although the argument for this one is a bit more fraught, not only because Thomas Jefferson, after cribbing these rights from John Locke, changed Locke’s third unalienable right into the pursuit of happiness; Locke said the third was the right to property, meaning the right to own the fruits of your own labor. That’s a different conversation. It’s also fraught because Jefferson was one of history’s greatest hypocrites, writing that all men are created equal while being attended by James Hemings, his wife’s half-brother — Jefferson’s own brother-in-law, who shared a father with Jefferson’s wife — whom Thomas Jefferson owned. Jefferson also, of course, owned James Hemings’s sister (And Martha Jefferson’s half-sister) Sally. And he owned his and Sally’s six children until his death. All men are created equal, eh?

Regardless of who wrote the words, though, the ideas are sound as written, if not as Jefferson embodied them and helped to codify them into the founding documents of this country. All people are created equal: each and every one of us is a unique individual, essentially capable of thinking and feeling, and in possession of free will. Therefore each and every one of us has the unalienable right to life and liberty, both.

Both.

That’s the trouble with this argument. It’s not that life (which I would argue is represented by safety; I’ll get to that in a second) is more important than liberty, nor that liberty is more important than life. It’s that you cannot separate the two.

Is safety the same as life, here? I don’t want to argue a red herring, to make a false equivalence between the safety in this argument and the right to life in the Declaration of Independence. But what do we mean by safety? Safety, I think, represents the assurance of continued life; like the pursuit of happiness, it is the right extended into the future. If I am safe, I not only know that I am alive right now, but I expect that I will continue to be alive in future, and so I am confident and comfortable in that expectation. In its essence, safety is about the preservation of life over time — and also the preservation of liberty, without which life is meaningless and so too is safety. I know that’s a circular argument, but really: if you were sure that tomorrow you’d be alive, but you’d be in jail, would you say that you felt safe?

And on the other side, if you were free to do as you wish, but you knew you would die tomorrow, would you really feel free?

I know the knee-jerk answer to that second question, from people who agree with the meme (probably my friend as well), would be a resounding HELL YEAH BROTHER! Because part of this argument is based on a quintessentially American/(toxically) masculine ideology that not only honors, but pursues and relishes, death, especially death by martyrdom on the altar of freedom. But while self-sacrifice is honorable and noble, and I am grateful for those who have sacrificed their lives for me — those sacrifices did not ensure the continued existence of liberty. They (depending on the specific situation) may have helped to eliminate a present threat to liberty with their sacrifice — probably also a threat to life; while the Fascist regimes in WWII were certainly a threat to liberty, they were clearly a much more dire threat to the essential existence of millions if not billions of human beings — but that doesn’t ensure, cannot ensure, that liberty will continue into the future.

Only safety can do that.

Now: it is certainly true that some attempts to limit liberty are presented under the guise of promoting safety; those must be guarded against. But that is not, despite the fanaticism of some liberty-lovers, true of every single attempt to ensure safety, nor even every attempt to limit liberty — some are presented as morally correct, for instance, regardless of whether they create more safety; like certain White House occupants sending certain Federal troops to certain cities to, errr, safeguard statues. That is certainly an attempt to limit liberty, but there’s not really a way to claim that keeping Robert E. Lee atop his horse atop a marble pedestal will make us safer. (There is some attempt, in the name of law and order, to claim that those who would pull down statues are threatening to create — or actually creating — chaos and danger for Americans. But let’s not buy into the bullshit, yeah? The only safety really being promoted there is the safety of the monuments, and the comfortable white supremacy they generally represent.) It’s like the argument that every single gun law is an infringement on the right to bear arms: that’s not really true. The essence of the Second Amendment is to preserve the right of self-defense — which preserves both life and liberty — and so long as one is able to do that, the right is uninfringed. Slippery slopes are not an argument, they’re a rhetorical scare tactic.

It is also true that some attempts to create safety also bring an unacceptable limitation on liberty; I think that’s the argument against lockdowns as a measure against the pandemic. As I think this year has made clear, though, temporary limitations on liberty become more acceptable when they are more effective in preserving life; the way to avoid a restriction of liberty is to find a way to have your cake and eat it too, to ensure safety while also preserving liberty — which in this case would be: masks. Masks are a way to effectively preserve safety by stopping the spread of Covid-19 while also not infringing on liberty, because so long as everyone wears a mask, we can continue with almost all of our preferred activities.

Brief aside to squash this nonsense: Liberty does not mean an unlimited right to do whatever the hell you want, to say no just because someone else says yes, to insist that somehow you don’t need to wear a piece of cloth on your face just because you don’t wanna BECUZ THIS’S AMURRRRRRRICA. It means the ability to control your own actions based on your rational decisions, so long as those actions don’t harm anyone else’s ability to do the same. Anyone making a rational decision not to wear a mask — i.e., “I have claustrophobia and the masks cause panic attacks, so instead I MAINTAIN A STRICT SOCIAL DISTANCE AND MAYBE WEAR A CLEAR FACE SHIELD” or “I don’t enjoy wearing a mask SO I DON’T GO OUT IN PUBLIC” — is fine; those are rational decisions, and I doubt anyone would have a real problem with those. That’s why exceptions for health reasons are written into every mask ordinance, and why no mask ordinance mandates people leave their homes. Now, it is certainly true that, all else being equal, the individual should be the one to decide for themselves what is a “rational” basis for their own decisions; but in a pandemic, the actions of individuals have outsized impacts on the life and liberty of others, and therefore some limitation of an individual’s actions is reasonable. The outsized impact on others means that one cannot make a determination of a rational action depending only on one’s own individual will. It means a reduction of one’s ability to choose for one’s self.

To preserve safety. And liberty. Because that’s what it means to live in a society. People who want to be so fanatical about their liberty that they accept literally no restrictions on their liberty imposed by others can still make that choice: they just don’t get to be a part of our society. Society requires compromise. Them’s the breaks. Your right to swing your fist ends where my nose begins, so if you want to swing your fists without any boundaries, get the fuck away from my nose. And then go nuts. Feel free.

Benjamin Franklin gave us one of the more popular arguments about this issue. He said,

“Those who would give up essential Liberty, to purchase a little temporary Safety, deserve neither Liberty nor Safety.”

Now, this quote, like everything else from the Founding Fathers — and, well, everyone famous ever, in this age of disinformation inundation (™) — is pretty regularly misquoted. A Google search for this one gets me this meme, which changes the quote pretty appreciably:

(It also gets me this one, which is hilarious because there’s absolutely no way Benjamin Franklin said this — and not just because “guy” was not commonly used to mean “that fellow over there” until around 1850, 60 years after Franklin’s death BUT MOSTLY BECAUSE OF THAT:)

(I also really want that not to be a portrait of Franklin, but it probably is. Oh, well.)

But case in point, the comments on the meme that my friend shared had this image in them:

![Image may contain: 3 people, beard, text that says '12:23 Kacey Elise Wheeler Kacey Elise Wheeler Yesterday Extreme Liberty 10:55 This shirt our Scofflaw collection has been really popular lately! Get while it's hot! [Link below] ...See More Those would upliberty purchase alety are bitches. Beajamin Franklin (probablyi Like Comment Share Whoolor ខ'](https://scontent.fphx1-2.fna.fbcdn.net/v/t1.0-9/116118289_3113653262088849_2970895150707464983_n.jpg?_nc_cat=100&_nc_sid=1480c5&_nc_ohc=k59cdIldaTMAX8CHtSa&_nc_ht=scontent.fphx1-2.fna&oh=2af496e3659c3e44e40f962e37528fbf&oe=5F4C81C4)

Which really represents what happens when people stop thinking about this stuff. Nothing wrong with wearing a t-shirt, of course; but this is not an argument, any more. Now it’s silly. Now it’s a meme.

But the best and most important thing about Franklin’s actual statement is this: it doesn’t mean what we think it means.

WITTES: The exact quotation, which is from a letter that Franklin is believed to have written on behalf of the Pennsylvania General Assembly, reads, those who would give up essential liberty to purchase a little temporary safety deserve neither liberty nor safety. [emphasis added]

SIEGEL: And what was the context of this remark?

WITTES: He was writing about a tax dispute between the Pennsylvania General Assembly and the family of the Penns, the proprietary family of the Pennsylvania colony who ruled it from afar. And the legislature was trying to tax the Penn family lands to pay for frontier defense during the French and Indian War. And the Penn family kept instructing the governor to veto. Franklin felt that this was a great affront to the ability of the legislature to govern. And so he actually meant purchase a little temporary safety very literally. The Penn family was trying to give a lump sum of money in exchange for the General Assembly’s acknowledging that it did not have the authority to tax it.

SIEGEL: So far from being a pro-privacy quotation, if anything, it’s a pro-taxation and pro-defense spending quotation.

WITTES: It is a quotation that defends the authority of a legislature to govern in the interests of collective security. It means, in context, not quite the opposite of what it’s almost always quoted as saying but much closer to the opposite than to the thing that people think it means.

SIEGEL: Well, as you’ve said, it’s used often in the context of surveillance and technology. And it came up in my conversation with Mr. Anderson ’cause he’s part of what’s called the Ben Franklin Privacy Caucus in the Virginia legislature. What do you make of the use of this quotation as a motto for something that really wasn’t the sentiment Franklin had in mind?

WITTES: You know, there are all of these quotations. Think of kill all the lawyers – right? – from Shakespeare. Nobody really remembers what the characters in question were saying at that time. And maybe it doesn’t matter so much what Franklin was actually trying to say because the quotation means so much to us in terms of the tension between government power and individual liberties. But I do think it is worth remembering what he was actually trying to say because the actual context is much more sensitive to the problems of real governance than the flip quotation’s use is, often. And Franklin was dealing with a genuine security emergency. There were raids on these frontier towns. And he regarded the ability of a community to defend itself as the essential liberty that it would be contemptible to trade. So I don’t really have a problem with people misusing the quotation, but I also think it’s worth remembering what it was really about.

In the end, the things we need to remember are these: safety is important. Preserving life is important. The reasonable assurance of future safety is also important — I don’t want to get into Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, but liberty is waaaay up at the top of the pyramid, around “self-actualization,” and safety is at the base, the second level just above food — and, dependent on circumstances, justifies a limitation on individual liberty. The preservation of liberty is equally important — but because liberty is more abstract than life, it requires more careful thought to reasonably determine what is, and what is not, a threat to liberty.

The whole reason we have the right to liberty is that we have the ability to reason. If we want to protect that right, then we must use that same reason to know when it is actually under threat. We have to think.

And stop taking memes too seriously. You know: like I just did.