I have been a high school teacher for a very long time. Too long, in some ways, because I have watched education change enough in that time to make me very nearly obsolete, and if you stay in a job until your job doesn’t exist any more, that’s too long. I fear that the day is coming when English teachers will not exist: and possibly the day when teachers will not exist.

I’m here today to try to forestall that day. Not for myself – if I reach a point where I cannot teach, I will move into janitorial work, and be quite happy; probably happier than I have been as a teacher. After 25 years of cleaning up student writing, I would rather clean up public restrooms. It’s less work.

But it’s also less important work. Not unimportant work, it’s incredibly important because janitors keep our world working, and keep it livable – but for me, as someone who works in education, that work is more important. I’m just saying custodial work is a good backup for me. I worked in maintenance for five years before I became a teacher, and I liked it. In some ways more than teaching.

So if I liked being a janitor more, you may be thinking, why am I a teacher? And why do I still like and sometimes love being a teacher, despite the issues in education that I deal with every day?

It’s because I love humanity. I think we are incredible. I believe we have infinite potential for goodness, and infinite capacity for wonder. What we have achieved as a race is miraculous – and also sometimes terrible – and despite our almost limitless ability to dream and imagine, we can’t imagine how many more miracles we can achieve. And, hopefully, how many terrors we can avoid, or even eliminate, in the future.

And the key to that, the key to unlocking our potential and achieving progress and positive growth, and to actually making miracles real, is education.

That’s why I’m a teacher. Because my faith, my zeal, my heartfelt belief, is this: the best thing about all of us is that we are human, and the most important thing one can do is help us all become better humans. That’s what I try to do as a teacher. And that’s why I’m here today, speaking to all of you about school. Because I want to help you all to learn something about which you have been deceived – or at least misled. I don’t think any of you really understand what school is or should be – and what you think it is, what you have been told the purpose of school is? That’s a lie.

The lie is that school is about money. All of you students have been told that the purpose of school, the reason you are here and the reason you should try hard and do all of your work, is because that way you can get into a good college, get a good job, and make good money. You’ve been told that all along – though in elementary school it may not have been stated explicitly; but back then you were certainly told, with absolute sincerity, that the purpose of your schooling was to prepare you for the next step, which would be harder, and would matter more: 2nd grade is meant to get you ready for the rigors of 3rd grade, 3rd grade gets you ready for 4th; all of elementary school is preparation for middle school, which is preparation for high school. And all the way along, more often the farther you get in your thirteen years of compulsory schooling, you have been told that the goal of high school is to get you ready to go to college. So that you can get a degree, so you can get a good job, so you can make good money. And since schools also tell you that the next stage is always more important than the current one – “When you get to high school, things get serious, that’s when grades really matter” – the clear implication is that the final goal is the one that really, really matters: college, degree, money. Did you absorb the message in 2nd grade that everything then was intended to prepare you for college and a job and good money? Maybe not, but the cumulative effect of all of this is the same: the goal of school is – money.

Teachers, and especially administrators, you have said this. You have said it to all of your students, probably with certainty, certainly with absolute sincerity. All of you have lied. All of you have misled all of your students. Don’t feel bad: it’s what you were taught, what you were told, what the whole apparatus and engine of the educational system forced on you. So you didn’t know, you couldn’t even think, that it might be a lie. This is some of the power of education: it can influence our beliefs, and therefore our behavior, in pernicious ways as well as positive ones. As always, the pernicious influence is easier. The idea that school is intended to help students make more money is a pernicious lie, and I need to convince you to stop saying it, to stop thinking it.

Don’t take this as a personal attack, either, teachers: I’ve said this too. With certainty. With absolute sincerity. Because it’s what I thought, and it’s what I was taught. But luckily for me, I had an extra advantage that most teachers don’t have, something that helped me realize the truth: I’m an artist. And I’m married to an artist.

My wife and I both went to college to study art. And though I ended up studying education – one of the more useless endeavors of my life – I earned my degree in art, specifically in literature. My wife, who is stronger and braver and smarter and better than I am, stayed with art all the way through. And she had one of the most difficult undergraduate programs I’ve ever heard of; harder than any pre-law or pre-med program, I would be willing to wager, and with far less prestige.

And here’s the thing, the magic secret: she didn’t do it for the money. Neither did I – though I did sell out and become a teacher. Actually, it’s not the becoming a teacher that was selling out; I still reflect and promote the ideas of my art in my teaching, and I am proud of the career I have had, because it is a noble vocation, when it is done right. But I should have kept studying art while I was in school. I hate to think of the potential I lost, the opportunities I walked away from by switching from literature to education. And it’s funny: just as my time in public school didn’t prepare me successfully for college, my college education didn’t prepare me successfully for my career in public school education. The time I spent studying art was far more useful to my teaching than my training in how to be a teacher.

It was in teacher training that I was first trained in the Big Lie, though of course I heard it in some form or other all the way through my own K-12 schooling: the idea that the purpose of school is to get students higher incomes than they would get without it. I was shown the statistics, the data, the graphs, that argue that college graduates make more money, on the average, than non-college graduates. I was shown this, and told to use it on my students, because it’s one of the most effective ways to get students to take school seriously, to work hard and therefore (incidentally) to learn. I assume that’s why all trained educators in this country have been shown the same data: because scaring children with threats about their future is effective. It’s cruel, essentially abusive, and it has some quite severe secondary and unintended consequences, as we are now discovering; but it’s effective. It makes those lazy little punks – that’s you, students – work harder and try more. At least some of them. At least some of the time.

Look: you can’t blame us. Teaching is hard. Everything about it is hard. Organizing curriculum is hard, planning lessons is hard, finding and adapting materials is hard. It’s hard to stand in front of a room and command attention, let alone respect. It’s hard to manage a room full of individual people and get them all to focus, together, on one thing. It’s hard to communicate clearly, and hard to understand children who haven’t yet learned to communicate clearly.

(Let me just say one thing to all the students here: speak up. I’m old; I’ve lost some of my hearing. I cannot understand you when you whisper, when you mumble. Whatever you have to say to me: speak up, please.

(And I’ll try to talk slower.)

And then, after completing all of those difficult tasks, teachers run into the biggest difficulty of all, the one that feels insurmountable: getting the students to do the work. We create this curriculum, design these lessons to deliver it, gather the materials, summon all of our strength, invent positive energy from somewhere, and teach our hearts out: and then all of you students, just – don’t do it. There are many individual reasons why you don’t do it, but in a large number of instances, maybe more common than any other, the reason you don’t do the work is just because you don’t want to. You don’t feel like it. You don’t see the point. You don’t think it matters. You don’t care.

Confronted with that, over and over in student after student, day after week after month after year, teachers have reacted understandably: we try to MAKE you care, dammit! Sometimes we do it angrily, resentfully, with hurt feelings; because we care. And when you care, it hurts to try so hard and have somebody just say, “Nah.” That’s why teachers then try to scare students, that’s why we threaten.

“Your boss won’t accept this kind of work when you have a job.”

“Your college professor won’t care about you, so they won’t make exceptions for you: they won’t even know your name.”

“You think you can act like that out in the real world? Think again!”

Hurt people lash out. We may tell ourselves we’re doing it to be helpful, but we’re doing it because we’re hurt. It makes it easier for us to tell the lie, because the lie is hurtful, where the truth is just difficult – and we’re lashing out at those who hurt us. We shouldn’t do that, but also, maybe all you students should stop hurting your teachers. When a student comes to my class and says something like “This is boring. Can we do something fun instead?” to my face, every day, I definitely want to snap at them about how their attitude won’t be acceptable in the future. Because it’s just not right to insult someone’s passion the way students insult mine.

So it makes sense that teachers have done this, that we’ve told this lie. It makes sense that we’ve structured school, and thought about how we can teach our subjects, and explained this whole endeavor to students, on the basis of this fundamental assumption, this base falsehood, that the purpose of school is to prepare students for the real world, specifically for college, so they can get good jobs and make good money. It makes sense – though, teachers, I won’t take us off the hook entirely, because we really should have recognized the falsehood in this, and seen the hypocrites we make of ourselves, when we tell our students they should study hard specifically so they can make more money: because we are all so very well-educated, and worked so hard to become so, and we are so poorly paid for that effort and education. Did you all go to school, do all that work, and then take this very hard job, for the money?

Neither did I. (Though also, I expect and deserve and demand that I get paid what I am worth. So should we all.)

I do need to point out that we make this claim about the purpose of school in more ways than just talking about money. We do also talk about getting a “good” job, by which we mean a job you like and find fulfilling, a job that you feel has value, to yourself or to society or both. Teaching is all of those things for me, as it is for many of my colleagues; and the money has been generally sufficient, if not actually good, or representative of what I’m worth. We do also talk about getting our students prepared, with skills and knowledge, for the real world, beyond and apart from college. I think we do that, a little. Not enough, though also, here we run into a question of how much someone can be prepared, in school, for the world outside of school, and also how much someone should be prepared in advance of actually living. But regardless: our efforts to prepare students for the real world, as we call it, are founded on the same principle: we try to get them ready for their jobs. We want them to have work skills, and know how to find a job, apply for and interview for a job, succeed in a job. When we talk about our students’ future – other than some basic insincere lip service to the worn cliches “You can be anything you want to be!” and “You can do anything you want to do,” – it’s always the same basic idea. It’s all about the money.

Okay. So those are the lies. Now: are you ready for the truth?

Deep breath.

The truth is, you can not be anything you want to be. You can only be yourself.

The truth is, you cannot do anything you want to do: there are limitations on all of us, some internal, most external.

The truth is school does not prepare you for college or for work. Only you can do that, and no matter how well you do manage to prepare yourself, you will still be surprised, and sometimes unprepared and overwhelmed; and to some greater or lesser extent, you will fail.

The truth is, school is not preparing you for the real world: you are already in the real world, and you always have been. And no, it doesn’t get better. It doesn’t get easier.

The truth – the big truth, the last truth – is that the purpose of education is not, cannot be, and should not be stated as, helping students to get a good job or to make more money.

The purpose of education is to create more life.

***

Okay, that was a lot of truth. Take another deep breath, and then I’ll soften it up some, make it easier to swallow and to digest.

By the way: we absolutely should teach our students how to breathe. There’s nothing more important. Literally.

Okay: now for the softer side of the truth.

While it is true that you can only be yourself, that is also the very best thing you could ever be. Because every single one of you, of us, is as good and valuable and worthy as every one else; and there is also no other person you could be as successfully as you can be yourself. It’s also true that figuring out who exactly you are is incredibly difficult and complex, and the work we do on that project in schools is good work. You get to explore your self and your society and your skills and interests, even while we are barking at you that you need to master proper MLA format for your resume.

While it is true that there are limitations on all of us, which keep us from doing anything we want to do, limitations can be overcome. Muggsy Bogues played a full career in the NBA despite being only 5’3” tall. Also – and this may be even more important – a lot of things we think we want to do are actually really bad ideas. When I was 6, I wanted to be a stage actor, a fireman, and an astronaut. All bad careers for me, for the person I became – especially all at the same time.

The truth is that school does not prepare you completely for college or work: but the truth also is, it helps. We will, as I said, always fail, in college and career and life; but no failure needs to be total, or permanent. Failure always precedes growth. And – heh – school can prepare you for failure.

Unfortunately, the truth – and I cannot soften it – is still that school does not prepare you for the real world. But that’s because you’re in the real world, right now, while you are in school, and there’s no preparing for it, for any of us. There is only living it. Experiencing it. Learning from it. That’s all we ever do, whether in school or not. I do think it’s important that we teachers stop telling students there is some distinction between school and the real world, especially with the implication that the real world is somehow worse, harsher or harder, colder or crueller. People who really think that do not remember what it was like to be in middle school or high school. Or they do not understand the situations that many students, many children, live through. As I said: it doesn’t get better and it doesn’t get easier; but you will get better. And then, if you can, you will make your life better. And that process will continue for as long as you keep trying to learn and improve: always in the real world.

Last one – and, because I know my persuasive rhetoric, this is the important one. This is the point. This is what education is for.

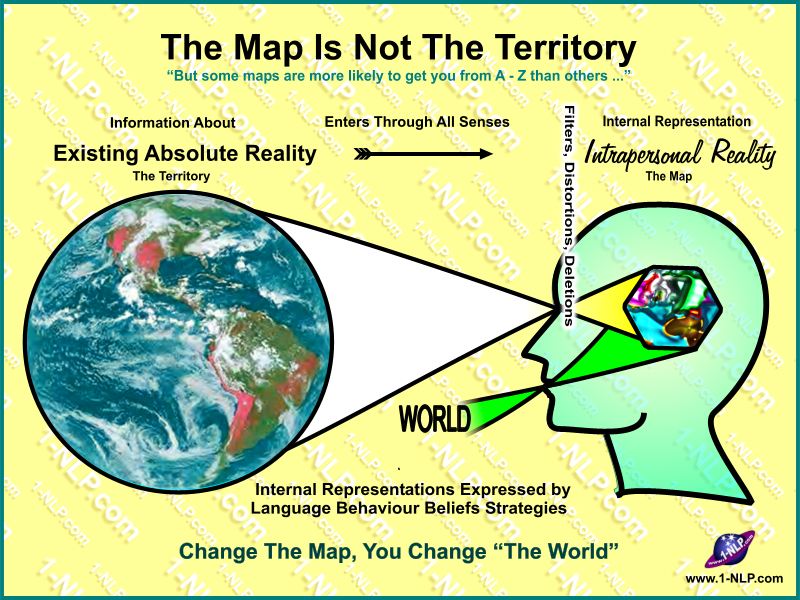

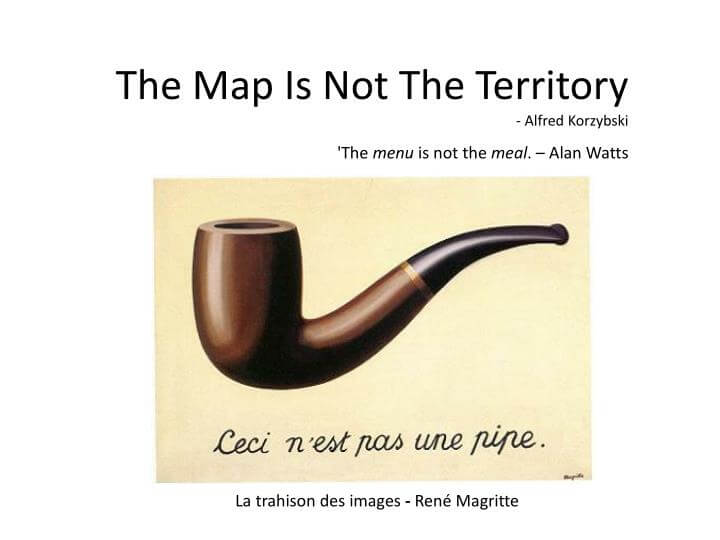

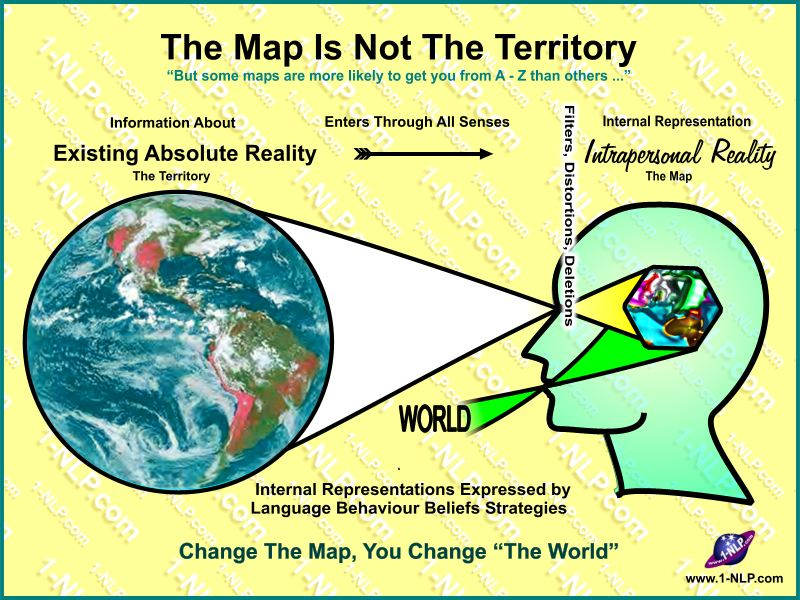

Our world has, I believe, an objective reality. It’s not just in my mind, or in the Matrix. The world would – will – still be here when I am not here to perceive it; it will still be the same world when all of us are gone from it. Although it will be quieter, and less messy. No matter how I imagine the world to be, whether I think the Earth is round or flat, 6,000 years old or 4.5 billion, floating in space or resting on four elephants who are standing on a turtle – there is a truth, a real situation that I don’t change through my perception of it.

However: my perception of the world shapes my world, changes how I experience it, more fundamentally than I think we realize – certainly more than we think about very often. How we see determines what we see. We cannot perceive things that we cannot imagine existing; sometimes we cannot perceive them intentionally, consciously. Take the flat Earth example. If I believe, absolutely, that the world is flat, then there are things I will not do, places I will not go, because of my belief, because of my perception. I will not get on a plane that I think would fly off the edge of the world. I will not go to the world’s edge, let alone beyond it – so I will never see that there is no edge. So even though the world is in fact round, I will never perceive the world as round, because I will avoid – or more simply, deny – anything that would prove to me that the world is round. So for me, functionally, the world would be flat. And I will miss out on any experience associated with the round Earth. My world, shaped by my perception, would be less full: only two-dimensional.

Let’s take a more realistic and more common example. If I were a racist, and hated, let’s say, plaid people, then I would avoid, or dismiss as unworthy of my time, any and all plaid people. They would essentially not exist in my world except as an amorphous abstraction for me to hate and fear and blame. I would never get to know, never get to appreciate, never get to love, anyone who is plaid. And therefore my world, my life, would be smaller.

Because plaid people are some of the finest people there are.

And if you don’t know any plaid people – or, even more shocking, you somehow think that they don’t exist – I think you need to open your eyes and pay more attention. America’s no place for plaid-deniers.

But in all seriousness, this fact, that perception shapes reality, is true in all ways: things that we can’t understand, we avoid; things that we can’t conceive of, we don’t even perceive. And in contrast, when we have heightened understanding, we have heightened perception: my wife’s experience of an art museum is much richer, much fuller, than mine, because her knowledge of art, and her experience with creating art and the deep understanding of the artist’s craft she has thereby, lets her see the works on display in more ways than I can, who makes art only with words. My experience of literature is similarly fuller than most people’s. My dog’s experience of the world of smells is many thousands of times more complex and interesting than my experience of smells: which is why he chooses to sniff cat poop, which I simply avoid. Because he finds it interesting, and I just think it smells gross. But I have to assume that if I could smell what he can smell, I would interact with cat poop the same way he does: my nose would be riveted to every turd. Think how much more enjoyable it would be to live with cats, then. Having the litter box in the house would be a benefit. Maybe we’d put the box on the coffee table. Make it a conversation piece.

I know that sounds bizarre and insane. It sounds that way to me, too. But understand: it only sounds that way because of how we perceive cat poop. Or rather, how we don’t perceive it. How our experience of the world is limited by our range of perception.

Education can change that (Maybe not with cat poop.), because education can introduce us to things, and show us how to perceive them. I wasn’t born reading literature the way I do; I learned that. Because I learned it, my experience of reading is better than most people’s. My world of books is larger, more vibrant, more diverse, more entertaining, more inspiring, more challenging, than most people’s book world. Not because I’m better than other people, not because I’m just built different: because I have been educated. Because I learned. Because I learned how to read and understand what I read to an unusually high degree, I have a larger world to live in. It means I can find greater pleasure and fulfillment in the world of books. I will never get tired of reading books. I will never be bored, not as long as I can get my hands and my eyes on books. I can still perceive all the non-book things as well as all the rest of you can – though some people perceive individual pieces of non-book-reality better than I can, because I don’t know much about cars or sports or calculus, or about being a parent, or about traveling to other places or into other cultures – but in the areas where I learned well, my world is larger than the world of people who didn’t learn as well. In all the areas where I am not ignorant, my life is larger than the world of ignorant people. I live a larger life, in a larger world, than someone with less education with me.

That’s why I’m a teacher. Because I love humanity. Because I want to help people to live larger, fuller, richer lives. To have more chances to be human, to be more human. To make miracles. What else could I possibly do that would be as valuable, as important?

But, you see, my work has, of late, become less valuable. Less effective, and therefore less important.

Because my students are less willing to work with me, to listen to me. They are less willing to learn.

But that’s our fault, teachers, parents, adults in general: because we’ve been lying to them. And they have caught on. These are the unintended consequences of our choice to use the threat of future poverty and failure to scare our students into obedience. Rather than explain the real value of education, even though the idea is complicated, even though it is hard to accept, we have chosen to use the simple lie that the entire point of education is to prepare students for future work. We still tell them, as we have for years, that going to college is the best way, even the only way, to get a good job and make good money, and the point of compulsory public education is to prepare them for college and for jobs – and that’s it. It’s not all we think education is for, but when we are frustrated with difficult and disobedient students, we don’t usually talk about the wonderful benefits of education: we just threaten them. “If you drop out, or get expelled, how will you get a good job? You’ll be flipping burgers for your whole life!”

But, see, we have now gone through a pandemic, and more than one recession; today’s students are in the world of social media, which gives them access to people’s lives and internal thoughts. So they’ve seen behind the curtain, they’ve torn down the veil. They know that there are countless people who have good jobs without ever having finished college, and countless people with lots of education who have miserable jobs. And now college is so absurdly expensive that even those who would want a college-level job – for whom a job that required a college degree would be a “good” job – are not willing to accrue the debt to get that job, and so they’re looking for different jobs, ones that are easier to get, that have fewer requirements. Or, more often than I think we educators realize, they have come to the conclusion that life is not, and should not be, defined by a job: and so what job they end up with simply doesn’t matter to them, as long as they make enough to survive and do what they want to do. What they want to think about and plan for is all the non-job parts of life.

So here you are, students. You’ve been hearing for years, again and again, that school is necessary for getting into college and getting a good job. And you don’t want that. And you know that we are lying to you, that you don’t need college for many good jobs. You also know that life shouldn’t be only about a job.

What, then, is the value of this education we offer and demand, for a student who doesn’t want what we have claimed is the main and even the only goal of that education?

There isn’t any. So you don’t want it. Of course not.

And the more we try to threaten, and cajole, and cozen you into doing the difficult work of education anyway, the more you resist. Of course: you don’t like being lied to, and you don’t like having your time wasted. Wasting time is wasting life, and we all want all the life we can get.

So you ignore and evade and escape education that is nothing for you but life-draining, time-wasting oppression.

And therefore you remain more ignorant than you could be. Not totally ignorant, of course, because you learn on your own. But school could teach you so much more than you can easily learn on your own; and without putting effort into school, you will absolutely know less than you would if you could really do this the way it should be done.

And since you will know less, therefore you will have less life.

***

It has to stop. We need to stop telling students that school equals college equals job equals money. We need to stop focusing on money. I don’t teach literature because it makes money, either for me or for the students – or even for the authors, who I do think deserve money for their work; but that’s not why I want the book, and it’s not why I want to teach the book. I do it because literature expands and improves my experience of being human: and I want that larger life. And I want other people to have what I have. Especially now: because the world kinda sucks. And especially the kids I teach: because being in middle school and high school kinda sucks.

Teachers: we need to tell our students the truth: school sucks, but education will make your life suck less. It will give you more life, and a better life, because it will let you understand more, and therefore do more, and perceive more. And we need to believe this when we say it, and we need to want that for our students.

Otherwise we should all just give up and become janitors.

At least then the world would be cleaner.