Yesterday was my birthday. I had a great day: my wife and I went out for an incredible brunch at a restaurant in Tucson called Blue Willow – HIGHLY recommend the breakfast burrito, if you go – and then went home and had presents – I got two awesome t-shirts and a video game, Skyrim for my Nintendo Switch, which is a lovely thing mainly because Skyrim was one of those games I avoided when it was new, since I knew it was exactly the kind of video game I love most (sandbox swords and sorcery) and would therefore consume all of my waking hours once I opened Pandora’s Box and started playing it, and as I told all of my students at the time when they asked if I was going to play Skyrim, I have a job; which means that now I have been given permission to go ahead and let my free time be consumed, partly because I deserve and need nice things, and partly because the truth is that I will not actually allow ALL of my free time to be consumed, that I can be trusted to do what is necessary even if I would rather just dive back into the video game (Hold on, the t-shirts reminded me: I need to cull my collection. Be right back. [Got rid of seven shirts. Good progress.]) – and then we went to an arcade with friends, where I got to play pinball and a car racing game and a pirate shooting game and the BIGGEST SPACE INVADERS IN NORTH AMERICA, and then we came home and ordered Chinese food in and then had huge slices of an AMAZING cake. It was a great day.

Yesterday in Washington D.C., the Republican party passed Donald Trump’s “Death to the Poors” bill (I will neither call it the B.B.B. as that shitmouth named it – though honestly I appreciate the bald hypocrisy of that, coming from the party that has been loudly and repeatedly criticizing large omnibus bills for years if not decades, until said omnibus comes from President Turdtongue – nor talk about it as a tax cut bill as the news outlets insist on calling it, while they also name it as a Asslips’s “most significant accomplishment,” which is a wild phrase: just imagine talking that way about, say, Auschwitz, or the Night of the Long Knives, or the invasion of Poland, as Hitler’s “biggest achievements” to date. I will come back to hypocrisy.), which Pres. Butt-Teeth will be signing today, in a continuation of his efforts to taint and corrupt every single piece of American culture so that nobody can ever enjoy anything ever again in this country.

Not that this is my favorite holiday: I’m a vegetarian, and I live in Tucson, Arizona, so barbecues at the park are out on both meat-related and heat-related grounds; plus my dog is terrified of fireworks, and I personally dislike the strong possibility of wildfires being started by an idiot with a bottle rocket and a match. But there are, nonetheless, reasons why I want to celebrate this holiday, and hold onto it in the face of ol’ Colon-Throat’s attempted appropriation. And I want to write about it today because I realized that the reasons for me, for us, to hold tight to the Fourth of July are the very same ideas that I want and need to write about.

I wasn’t sure what I wanted to write about. Part of me doesn’t want to write at all: I just want to curl up on my couch, pet my dog, and play video games. (And not only because I just got Skyrim, though that is definitely part of the draw… I can hear it calling to me right now… No, wait, that’s my cockatiel Duncan screaming because he’s upset about something.) And while I want to rant about Donald Trump, and the Supreme Court, and the Congress, because all three branches of government have been captured by the proto-fascists who want to turn America into a white Christian ethnostate with a patriarchal dictatorship that is decidedly unChristian, I don’t know what the value would be in ranting: the people who would read it already agree with me, and it would just make them sadder than they already are because the horror is relentless and it’s hard to remain so ourselves; and the people who might read it who don’t agree would find it tiresome to just hear more ranting; and the people who are on the opposite side of these issues (who don’t read, but just hypothetically) would be giddy with Schadenfreudish glee, cackling about how angry I am and signing up for WordPress accounts just so they can comment “Cry more!” and throw down some of the memes I’ve been getting hit with because I have (foolishly) been commenting on news stories on Facebook. And I don’t want to create any of those responses.

I recognize that the most important thing we can do is spread good information, and so that makes me want to become a journalist, and share correct information, and – I mean, maybe I should do that. But I already have a job. And it’s a hard job, and I work hard at it. And I have a family which I love, but which, like all families, requires a lot of time and energy – and not that I begrudge that, I do not, I would spend all of my time and energy on my family if I didn’t have to work, and I look forward to the day when that happens; I’m just saying that I will not take time and energy away from my family in order to become a journalist. There are already better journalists, trained and professional journalists, out there doing that work, so I shouldn’t have to. Clearly my fight against misinformation is in my teaching, and I will continue to do my very best there, in every way I can.

But that leaves me with nothing to write about.

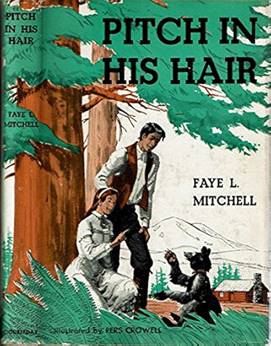

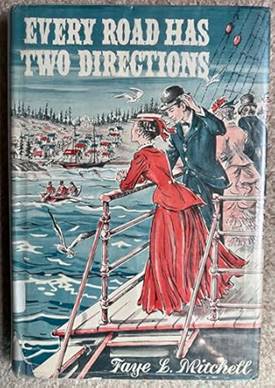

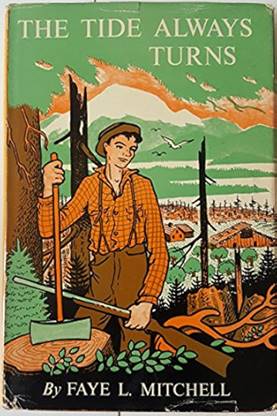

It is summer, and so that makes me want to write, because over the school year I am often too tired and burnt out and frustrated to write; but I have been facing this conundrum about what to write about, and I haven’t been writing much. (Also my summer has not been all that restful, but it’s mostly been family stuff, so I don’t resent it.) As I haven’t been writing, however, I have been trying to get back into my other great passion that I haven’t been able to spend enough time on: I’ve been reading. And one of the things I’ve been reading has been these:

These are my great-grandmother’s novels, published in the late 50s, when she had retired from teaching. (Have I mentioned that I come from a line of teachers and writers on my mother’s side? This is part of that line.) I’ve never read them before, partly because I never knew my great-grandmother; for most of my life I didn’t even know that she had written books or published them or that we had copies. So I’m reading them now, and they have shown me a couple of things. First, because these are young adult books, and historical/regional fiction (They are all set in western Washington, where the Mitchells lived and where both my grandmother and then my mother were born and raised, during the frontier times between about 1970 and 1890, when the Mitchells did not live there – Faye and her husband Burt emigrated from Kansas), they are not great literature in a canonical sense: but they are good stories. And this helps to settle in me something I have always struggled with, because I am not a writer of great literature, and though I don’t want to be, I always think I should be; but I think that in truth I am, like my great-grandmother, a storyteller, not a literary giant. And I would rather be that. Second, these books, because they are set where they are and because the main character, Abby Conner, is a young woman who wants to become a teacher and a writer and who talks about what it means to be a teacher and a writer, are helping me to be prouder of the teacher and the writer that I am, because I think that my great-grandmother would probably be proud of me, and I like that – and my Nonna, whom I loved and respected but who passed before I had even decided to become a teacher, would definitely be proud of me, and I love that. And third, because my great-grandmother clearly wrote about what he knew, I have been thinking about how I need to do that. Not with my novels, which are almost certainly going to stay fantastic and more about vampires and time-traveling pirates and magical dreams that change reality; but with these blogs, and with the things that I write every day: I need to write about what I know.

So this is what I’m going to do: I’m going to write about what I know.

So. What the hell do I know?

…

I used to be optimistic.

My wife talks about it, about how I used to be much more cheerful, and much more calm, and much more positive. She doesn’t make it sound as bad as I just did: she doesn’t say all those things at once, and she doesn’t say it with any kind of accusation or disappointment or anything – never “You used to be a lot more fun!” or anything like that. She has taken note of it out of concern for me: because my general demeanor has become darker and angrier over the last decade or so. And it’s coming out in ways and in places that I don’t like: I have had a hard time keeping myself from losing my temper with my students, and I have failed at that, and lost my temper, several times in the last few years, sometimes to my real regret. I am also having a hard time keeping my spirits up in order to push back against my wife’s occasional depressing outlook, which is sometimes something she needs me to do (Don’t we all?), and which I have not been doing as well as I used to.

I suspect this happens to a lot of people, if not to all of us. We lose our idealism, and our hopefulness – those of us who ever had it, that is, which is not everyone. But I think as time goes on, and life gets harder, and as people just keep on disappointing us, over and over again – say, by re-electing an orange-tinted fascist would-be dictator even after he tried to overthrow our government the first time: it’s hard to look down the road and think that it actually goes to a better place. And while Trump certainly wasn’t inevitable, the difficult and sad things that happen as we get older are inevitable: we lose people we love, and eventually we lose ourselves, and there is often a great deal of suffering on the way to that. As that happens to us more, and as we are shielded from it less, our lives become sadder in many ways, and it makes sense that we would do the same.

I do also think the last few years have been rough on people in this country. Trump’s two electoral wins and two administrations, the pandemic, the various economic and global crises: it’s been tough to keep looking on the bright side of this pile of shit. I certainly haven’t been immune to that. In fact, it has been directly detrimental to my optimism: because I keep thinking, and saying, and arguing, and preaching, that things are going to work out the right way: and I keep being wrong. I said that Trump was going to lose in 2016, both in the primary and then in the election, and I thought that he would go to trial for his crimes and that he would get convicted, and I thought he would lose in 2024. Wrong, every time. (Okay, he was convicted, but only of the least important one, and it didn’t affect his political ambitions in any way at all, which I also thought it would. Still: he is a fucking convicted felon, and anyone who claims it was only a politically motivated prosecution, you’re goddamn right, and it was a successful one, and it should have kept people from voting for him, and it was therefore the right thing to do – but I think we can see that, even though it was a politically motivated prosecution, that didn’t affect the general populace very much: the election is evidence that the jury was honest and sincere.) That record makes me not want to keep my hopes up: not mainly because I hate being wrong and looking dumb (though I do, both), but mainly because I don’t want to give people false hope and then have them fall farther and harder when my false hope is proven wrong. Again.

But okay: now let’s talk about the Fourth of July. (See, this is why I’m so goddamn wordy and circuitous in my writing, even though the only way to write great literature is to keep it short and simple, as much as possible, to edit even more than you write: because I’m not a great literary mastermind, I’m a storyteller, and this is how stories get told. Thanks, Great-grandmother. Actually, since I called her daughter Nonna, I’m just gonna call Mrs. Mitchell Grandnonna. I hope she would like that. And let me note that, as wordy and circuitous as I am, I get back to where I want to go. Eventually.)

The Fourth of July is a convergence of three of my heroes. Three of the greatest writers in American history, because all three were three of the greatest thinkers and idealists in American history. Not all the best people, but I generally think the art, and the truth, can transcend the people who discover it or create it. If you look at science, for instance, there is not and never has been a scientist who was worthy of the power of what they discovered: not Newton, not Darwin, not Einstein… maybe Carl Sagan. I don’t know if Galileo was a good man, honestly, but how could he possibly be good enough to live up to what he did for our understanding of the universe, for what he made possible? He couldn’t. The same with great artists: the people who affect the lives of millions and even billions of other humans in positive ways couldn’t possibly be good enough in and of themselves to really be seen as deserving of the praise that their impact deserves. Martin Luther King, Jr., could not possibly be good enough as a person to actually deserve the honor that he rightfully gets as the civil rights leader and genius communicator that he was, even if he hadn’t been an egotist who cheated on his wife. But his impact, his positive impact on the world, is beyond measuring: is beyond what one person could contain. So I am willing to praise the work, and the words, and the ideas, even if the person who created those things was worse than their impact.

This does not excuse J.K. Rowling, by the way, though I do also think the criticism of Harry Potter is lazy and vicious and incorrect; but Rowling is, it turns out, a terrible person who should absolutely be canceled entirely. While we all keep reading Harry Potter. Don’t worry, it will get easier when she is dead.

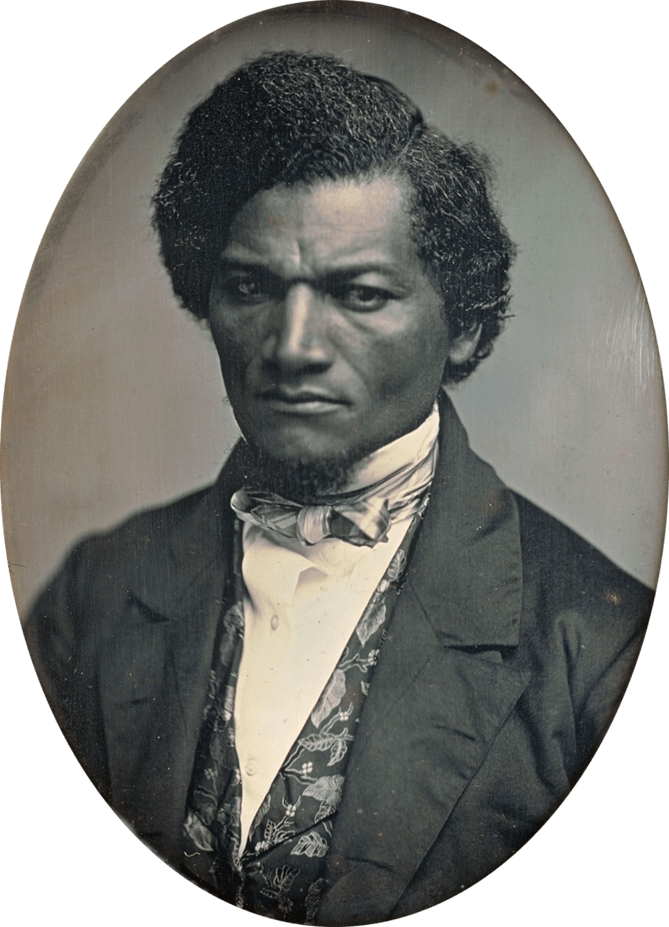

So: the three people who are connected by the Fourth of July and whom I find inspiring are Thomas Jefferson, Frederick Douglass, and Abraham Lincoln. (See what I mean about not the best people? Douglass was a saint, but I only say that because I don’t know enough about him to know the bad stuff; Lincoln was a racist egotist, and Jefferson owned his own children. But the point here is that we need to look at the work, and the ideas, and the words.) Thomas Jefferson, of course, wrote this:

When in the Course of human events, it becomes necessary for one people to dissolve the political bands which have connected them with another, and to assume among the powers of the earth, the separate and equal station to which the Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God entitle them, a decent respect to the opinions of mankind requires that they should declare the causes which impel them to the separation.

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.–That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed, –That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness. Prudence, indeed, will dictate that Governments long established should not be changed for light and transient causes; and accordingly all experience hath shewn, that mankind are more disposed to suffer, while evils are sufferable, than to right themselves by abolishing the forms to which they are accustomed. But when a long train of abuses and usurpations, pursuing invariably the same Object evinces a design to reduce them under absolute Despotism, it is their right, it is their duty, to throw off such Government, and to provide new Guards for their future security.–Such has been the patient sufferance of these Colonies; and such is now the necessity which constrains them to alter their former Systems of Government. The history of the present King of Great Britain is a history of repeated injuries and usurpations, all having in direct object the establishment of an absolute Tyranny over these States. To prove this, let Facts be submitted to a candid world.

Those two paragraphs might be the best argument ever written: because the words are perfect, the logic is perfect, and the idea was so much better than the people who formulated it that it has led to better outcomes and a better world for hundreds of millions of people, for two and a half centuries. We hold these truths to be self-evident.

All men are created equal.

(Which also means that we all suck. Just sayin’.)

And I think we know why this idea, these words, and this man are connected to this day, for me. For all of us.

Lincoln, on the Fourth of July in 1863, said this:

Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent, a new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.

Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation, or any nation so conceived and so dedicated, can long endure. We are met on a great battle-field of that war. We have come to dedicate a portion of that field, as a final resting place for those who here gave their lives that that nation might live. It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this.

But, in a larger sense, we can not dedicate — we can not consecrate — we can not hallow — this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have consecrated it, far above our poor power to add or detract. The world will little note, nor long remember what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here. It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced. It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us — that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion — that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain — that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom — and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.

This is sometimes described as the perfect speech – partly because it is so short, and therefore nothing that I ever could have produced – and there’s an argument to be made for that. I find it inspiring because I think it translates some of Jefferson’s ideals, which were intentionally more universal, into something more personal, more grounded: this is how the idea that all men are created equal comes to be an American ideal instead of a human one – though it is still, and always should be, a human ideal. Still, Lincoln and this address are why we as Americans should consider this to be something personal, something we own, not simply a truth that exists in the world. Jefferson and the Founding Fathers are part of that as well, because the Declaration of Independence was not just a statement of ideals, but also a political and pragmatic document (which is why I include the first paragraph in the quotation from it, and in what I describe as the perfect argument: that sets the purpose for the second paragraph, where all the intellectual brilliance is. But as a rhetoric teacher, purpose matters, so the first paragraph is part of that, and part of what Jefferson and the rest of them were committed to, like Lincoln.); but because the Founding Fathers were patriarchal slaveowners who didn’t want to pay taxes, their purpose doesn’t rise to the level of their ideals. Which makes them fascinating, really, because slaveowners who didn’t want to pay taxes somehow managed to formulate and then enact one of the greatest ideals in human history, that all men are created equal and that government should be based on that fact and all of the logical consequences of that fact, such as the necessity of consent; but Lincoln’s purpose in saying his words was, first, to honor the sacrifice of people who died for those ideals, which is one of the most important and perhaps most abused elements of recognizing the worth of all humans (and not something expressly focused on in the Declaration, not even in its lists of abuses and usurpations), and second, to maintain the existence of the nation based on that fact, and to help bring it closer to being a nation that lives up to its own purpose, a nation governed by a system based on the fact that all men are created equal. Those purposes are worthy of those words, of the ideas they express, as the words and the ideas are worthy of the purpose. Probably not so with Jefferson.

And then Douglass. I wish I could have heard Douglass speak, because unlike the other two, Douglass was a great speaker as well as a great writer; but at least we have the words he wrote down, and the story he told with them, the story of his own life. And if you don’t know why Frederick Douglass is connected to the Fourth of July, it’s because of this:

(1852) Frederick Douglass, “What, To The Slave, Is The Fourth Of July”

Frederick Douglass

Daguerreotype photo by Samuel J. Miller

That whole speech is worth reading. But let me focus on this:

Fellow-citizens, pardon me, allow me to ask, why am I called upon to speak here to-day? What have I, or those I represent, to do with your national independence? Are the great principles of political freedom and of natural justice, embodied in that Declaration of Independence, extended to us? and am I, therefore, called upon to bring our humble offering to the national altar, and to confess the benefits and express devout gratitude for the blessings resulting from your independence to us?

Would to God, both for your sakes and ours, that an affirmative answer could be truthfully returned to these questions! Then would my task be light, and my burden easy and delightful. For who is there so cold, that a nation’s sympathy could not warm him? Who so obdurate and dead to the claims of gratitude, that would not thankfully acknowledge such priceless benefits? Who so stolid and selfish, that would not give his voice to swell the hallelujahs of a nation’s jubilee, when the chains of servitude had been tom from his limbs? I am not that man. In a case like that, the dumb might eloquently speak, and the “lame man leap as an hart.”

But, such is not the state of the case. I say it with a sad sense of the disparity between us. I am not included within the pale of this glorious anniversary! Your high independence only reveals the immeasurable distance between us. The blessings in which you, this day, rejoice, are not enjoyed in common. The rich inheritance of justice, liberty, prosperity and independence, bequeathed by your fathers, is shared by you, not by me. The sunlight that brought life and healing to you, has brought stripes and death to me. This Fourth of July is yours, not mine. You may rejoice, I must mourn. To drag a man in fetters into the grand illuminated temple of liberty, and call upon him to join you in joyous anthems, were inhuman mockery and sacrilegious irony.

Here we see Douglass’s purpose, and the reason he also needs to be included in this list of great writers connected to the Fourth of July: because Douglass held this country to account for its hypocrisy. (Told you I’d come back to it.) Douglass showed, more clearly than anyone else, that the United States has never lived up to its ideals.

He said this:

I remember also that as a people Americans are remarkably familiar with all facts which make in their own favor. This is esteemed by some as a national trait—perhaps a national weakness. It is a fact, that whatever makes for the wealth or for the reputation of Americans, and can be had cheap will be found by Americans. I shall not be charged with slandering Americans if I say I think the American side of any question may be safely left in American hands.

I leave, therefore, the great deeds of your fathers to other gentlemen whose claim to have been regularly descended will be less likely to be disputed than mine!

My business, if I have any here to-day, is with the present. The accepted time with God and his cause is the ever-living now.

Trust no future, however pleasant, Let the dead past bury its dead; Act, act in the living present, Heart within, and God overhead.

We have to do with the past only as we can make it useful to the present and to the future. To all inspiring motives, to noble deeds which can be gained from the past, we are welcome. But now is the time, the important time. Your fathers have lived, died, and have done their work, and have done much of it well. You live and must die, and you must do your work. You have no right to enjoy a child’s share in the labor of your fathers, unless your children are to be blest by your labors. You have no right to wear out and waste the hard-earned fame of your fathers to cover your indolence. Sydney Smith tells us that men seldom eulogize the wisdom and virtues of their fathers, but to excuse some folly or wickedness of their own. This truth is not a doubtful one. There are illustrations of it near and remote, ancient and modern. It was fashionable, hundreds of years ago, for the children of Jacob to boast, we have “Abraham to our father,” when they had long lost Abraham’s faith and spirit. That people contented themselves under the shadow of Abraham’s great name, while they repudiated the deeds which made his name great. Need I remind you that a similar thing is being done all over this country to-day? Need I tell you that the Jews are not the only people who built the tombs of the prophets, and garnished the sepulchres of the righteous? Washington could not die till he had broken the chains of his slaves. Yet his monument is built up by the price of human blood, and the traders in the bodies and souls of men, shout —”We have Washington to our father.”—Alas! that it should be so; yet so it is.

The evil that men do, lives after them, The good is oft’ interred with their bones.

And this:

At a time like this, scorching irony, not convincing argument, is needed. O! had I the ability, and could I reach the nation’s ear, I would, to-day, pour out a fiery stream of biting ridicule, blasting reproach, withering sarcasm, and stern rebuke. For it is not light that is needed, but fire; it is not the gentle shower, but thunder. We need the storm, the whirlwind, and the earthquake. The feeling of the nation must be quickened; the conscience of the nation must be roused; the propriety of the nation must be startled; the hypocrisy of the nation must be exposed; and its crimes against God and man must be proclaimed and denounced.

What, to the American slave, is your Fourth of July? I answer: a day that reveals to him, more than all other days in the year, the gross injustice and cruelly to which he is the constant victim. To him, your celebration is a sham; your boasted liberty, an unholy license; your national greatness, swelling vanity; your sounds of rejoicing are empty and heartless; your denunciations of tyrants, brass fronted impudence; your shouts of liberty and equality, hollow mockery; your prayers and hymns, your sermons and thanksgivings, with all your religious parade, and solemnity, are, to him, mere bombast, fraud, deception, impiety, and hypocrisy—a thin veil to cover up crimes which would disgrace a nation of savages. There is not a nation on the earth guilty of practices, more shocking and bloody, than are the people of these United States, at this very hour.

Douglass said a lot that could apply to us today, which is why it is worth reading the whole speech. (And I’m thinking now I may teach it next year. We’ll see.)

But, since I have now gone on for far too long (Not gonna feel bad. Storyteller. Also, I was quoting.), let me get to my purpose: the reason why I wanted to talk about these three men and their writings on this day, the Fourth of July.

Because all three of these men represent hope.

If they did not believe that this nation could exist in its ideal state, or at least that it could come closer and that approaching that ideal would be better than moving away from it, they would never have said what they did. None of them lived in this nation in its ideal state, and probably none of them thought they ever would live in that nation: but they all believed it (or something close to it) could exist, and that that wonderful reality was worth fighting for. I know because all three fought to achieve it, for essentially all of their adult lives, with all of the considerable powers at their disposal. They fought, for years, for decades, in the face of insurmountable odds, of endless trudging through swamps of opposition, the stinking mud sticking to them and tainting everything they did and everything they saw, making absolutely no progress, for longer than some people have to live their whole lives.

But they kept fighting. Because they believed they could succeed. They did not give up. No matter what.

That’s what optimism is. It’s determination, and belief. It is hope. It doesn’t have to be based on reality and an understanding of the truth and the terrible odds stacked against us: but when it is based on that, it is that much stronger, that much more potent. That much more indomitable.

I don’t know if I’m indomitable. But I do know I’m stubborn as fuck. And maybe that’s the same thing.

I don’t know if I have that kind of optimism. But I hope I do: and so I’m going to keep fighting, and keep trying, and keep writing. Because I think that my purpose, and my ideals, are worth all of that effort, and all of that fight, and all of that struggle. And because I believe that the world I dream of is possible. Even if I never see it.

But I hope I do. And I hope you will, too.

Happy Independence Day.