Last week I wrote that the education system, for all of its flaws and issues, is necessary.

But is it really?

Really really?

I think that I am not sure. I want to say, without the shadow of a doubt, that it is: because education is necessary (That, I am sure of), and because there are so many people in the world who need education, there’s no way to tear down the structure we have now and build a new one — or even live without one entirely, and let people learn on their own — without losing a whole generation in the transition.

But that seems to me like an extraordinary statement: that we would lose a generation. We wouldn’t: they’d still be there, still be alive. I mean that they would lose their opportunity to gain the same education that every generation has had for the last 150 years in this country, and would lose, therefore, their ability to thrive in this culture and in this economy. But look at how much of that statement relies on the assumption that everyone should be like me, should be educated like me, that everyone should be like everyone else. I assume that the generation who would not get the current education from the system would suffer, as I know people suffer who do not succeed in education: they have to work harder, and they earn less, and they miss out on opportunities to experience life more fully: they don’t appreciate art, they are less aware of the wider world and what it has to offer, and are therefore more likely to be xenophobic and afraid of change and new experiences and ideas. But I also know that all of those things can be gained on one’s own, with travel and experience and exposure to other cultures and ideas and people.

When I say we would lose a generation, I mean that we would be saddled with people who wouldn’t be as productive, who would struggle more and need more help, and who would tend to resist and slow down our forward progress, and would certainly not contribute to it. We’d lose a generation of more of — us. People like us, like you and me. That’s what I imagine would happen if we stopped educating people. I assume they would gain the basic skills, from their parents and from educational games and Sesame Street and whatnot; and then I assume they would know little else other than entertainment, at least until they learned things the hard way, through experience, through life.

But.

That’s a lot of assumptions. And a whole lot of what I can’t describe as other than elitist bullshit. Because the core argument there is, without the system that made me, there would be people who would not be like me. Which assumes that I am how people should be. That being unlike me would be bad.

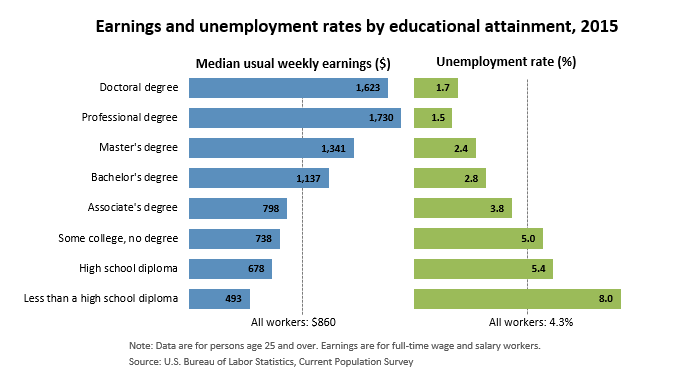

I don’t like it. I don’t like thinking that way, that my assumption of the necessity of education is just that, an assumption, and one based on elitism. Don’t get me wrong: there is evidence for it. Scads of evidence. Oodles. There are countless statistics which show the benefits of education:

Though now that I have looked at the Google search results, I see that the only statistics they show for “benefits of education,” other than benefits for certain kinds of education within the system such as the benefits of arts education or of inclusive education for students with disabilities, is exactly that one: that more education leads to more money. Which is not the most interesting argument for me, because I do not believe that life revolves around either career, or money; so using that as the sole focus for a discussion of education is obnoxious: I want to know what benefits there are, in addition to income, for the people who go through the school system. There are other benefits: primarily that more educated people have better health, more stability, and commit less crime. Here, this infographic lists several of them. (I was not trying to make a point about the total focus of education on earning money, but I guess that point is unavoidable, isn’t it? Hold onto that for a moment. Let me make this point, which is broader.)

That’s what I was talking about, that there are a number of benefits of education. (Here, this article from UMass [Woo! Home state comin’ through! Wait — what the heck is “UMass Global?] lays out the facts I have seen referenced before, with links to further resources to support the asserted health benefits associated with highly educated people, which are: 1. They’re likely to live longer, 2. They probably won’t experience as much economic or occupational stress, 3. They’re less likely to smoke, 4. They’re less likely to experience common illnesses, 5. They have fewer reported cases of mental health struggles, 6. They tend to eat better and maintain regular exercise habits, and 7. They’re more likely to have health insurance. I presume all the other benefits in the infographic are also supported by studies and statistics.) I have used these arguments in the past, in my own head if nowhere else (And 99% of the arguments I have in life are only in my own head. Since I teach argument, write arguments, and argue online on both Twitter and Facebook, that should give you an idea of how much of my usual headspace is filled with argument. [Jesus, I need to relax. No wonder my blood pressure has been going up.]), and I have heard them and seen them used many times to support the argument for education.

But here’s the thing. And again, I hate this — as you can tell by my obvious reluctance to actually make this point, and most of my arguments with myself over the past week have been between the part of me that wants to face this and the part that wants to hide from it — but I do believe that honesty is not only the best policy, it is the foundation of all other communication: so I need to say it.

None of those benefits are necessarily caused by education. All of them are only correlated. There is no reason, in most cases, to assume that the education itself caused the benefit.

People with more education earn more money in our society, yes. (Though of course, there are exceptions.) But is that because the education — the actual knowledge, not simply the achievement of a degree or certification– is necessary to earn the money? In some cases, most obviously doctors and lawyers and scientists and the like, the answer is emphatically yes, of course; but in many, many cases, the reason the higher income is correlated with the higher educational attainment is because those jobs insist on those degrees.

And I hope we all know that a degree is not necessarily because of actual education. I would make more as a college professor than I do as a high school teacher (Though really, not much more, unless I reached the most elite heights), and even though I guarantee that I could teach a college course better than many current professors, I can’t have that job because I don’t have the degree for it. I have the knowledge and skills and experience; and in my case, since continuing education is a requirement for recertification as a teacher, I have something like two to three times the post-graduate credits for a Master’s degree; but I don’t actually have the degree, so I can’t have the job.

For most of the rest, the correlation is far more connected to two other factors, which are certainly causative in our society: class, and race. Wealthier people have better health outcomes; and whiter people have better health outcomes. Primarily because health in this country costs money, and secondarily because the system is racist. Wealthier people commit less crime; whiter people commit less crime (Though that one is fraught for a bunch of reasons, because people of color are overpoliced and underpoliced simultaneously, so are more likely to be caught, arrested, convicted, and imprisoned for crime; in actuality, in this country, whiter people do commit more crime because all racial groups commit crime at about the same rates, and there are still more white people in this country than any other racial group. Most importantly, all crime rates are heavily dependent on socioeconomic factors, and those favor white people in the US — so again, the correlation is not causation in this instance. But to my point, it still ain’t because of education.) Wealthier people (Also older people) have greater civic and political engagement; whiter people have greater civic and political engagement.

Both of these factors, socioeconomic class and race, are also closely connected to — and causative of — educational attainment. Wealthier people have more education, because they can afford it and because they have more opportunity to pursue it: they don’t need after school jobs, or just to drop out and work; they don’t have to commute (or if they do, it’s in comfort); they don’t have to struggle for resources and materials like books and computers and access to libraries and so on. If they have kids (Statistically less often when young) while they are seeking education, they have greater access to childcare; ditto for providing care to older or disabled family members. People get more education when it’s easier to get, and when you feel rewarded for your successes in it, so this feedback loop is self-amplifying. White people — and again, this is largely because white people in this country are more often wealthier people — have all the same advantages. So this is mainly why educational attainment and these positive outcomes are correlated: because both are influenced causatively by class, and by race.

And then, as I noted briefly above, I have to also point out that many of the benefits overall are benefits economically: notice the “social benefits” in the infographic include “Gains in labour productivity.” And that whole third arrow section is about how all of society benefits when all of us make more stuff and make more money. I love the one one there about how society saves costs when individual citizens commit less crime and have better health. Maybe we should make motivational posters based on that. “Don’t do drugs, kids, or else you’ll become a drain on society’s resources.” So for all of those, the issue here is, there may be benefits of greater education — but for whom? In this society, where 90% of the wealth is held by 10% of the people, and almost all the gains in the past 50 years have gone specifically to that same 10% of the people, almost all the benefits correlated with education do not accrue to those who go through the system.

So. That’s the truth. The education system creates some positive outcomes directly: I do think that greater civic engagement is good for the people who involve themselves, and I certainly think that greater awareness and understanding of the system and how it works and what is going on helps to create that engagement. But I think we can clearly see from Donald Trump and the MAGA movement that strong civic engagement does not come only from people who are the product of the educational system. And there are, as I said, a number of professions which require education; and those are important both for society and for individuals who wish to pursue them, and so those opportunities coming from education are good.

But that’s where it starts to break down for me, again: because do people who study law, and medicine, and science, really need to go through the education system? For most of them, it works, and so it isn’t an obstacle to positive outcomes; but is it necessary? Are there people who would make excellent doctors even without education? What about lawyers?

That’s not the right question, though: of course people need education to be able to pursue those occupations. The question is: do people need to be educated by a system? Can they be self-taught, and successful?

And the answer is: Malcolm X. Who had an 8th grade education. Who taught himself in prison. And who then could do this. (That last one is an hour-long speech he gave. Without a teleprompter. Compare it to any politician you can think of, both in terms of content and presentation.)

He’s not the only example, of course. There are countless others, countless because we don’t usually keep track of people who are well-educated outside of the formal system, unless they do something we laud, such as earn billions of dollars or something similar. But Malcolm X was so incredibly intelligent, so incredibly capable, so incredibly knowledgeable — just so incredible — and only and entirely because of himself, with some influence and then support from others, including his family and his faith community. But never, in any way, was he supported by the system: and yet, what he could do, and what he did, is amazing. Simply amazing.

So the truth is, the education system is not necessary. It works, for the most part, for millions of people, and that’s good; but the existence of millions of people for whom it does not work, and the existence of countless people who don’t need the system to succeed, forces me to ask the question: is the system necessary even for those millions of people for whom it works?

And the answer is, I don’t know. None of us do. We have no way to compare: education is only one path, and there is no way to come back and choose a different path in the same life, to determine what would have happened because of that other choice. (Yes, that’s a Robert Frost reference. But did you need to understand the allusion to get my point? [I think your experience is richer if you did understand it, or if you click the link, read the poem, and figure it out. I’ll get to that.]) We can look at people with education who succeed, and people without education who struggle, and we can assume that education was important for them. But in both cases, we’re cherry-picking both the examples, and the definitions of “succeed” and “struggle.” By other definitions, and in other examples, education is irrelevant where it isn’t harmful.

So last week, when I wrote that the Labyrinth was necessary and important to contain the monster, I could only make it make good sense by joking about it: because otherwise the children are the only Minotaur, the purpose and reason for the construction of the Labyrinth, the thing at the heart of the edifice; and children are not a monster who must be contained. It’s pretty upsetting to think of them that way, and to think of school as a way to contain them — quite literally putting them in the box and making them stay there, without letting them out of it. I don’t want to be that teacher, or that person, who really thinks that. I don’t believe in my usual practice that I am that teacher; there are very few instances where I insist that a student conform to my rules or expectations. But I made the joke. And when I was thinking for this week about wanting to explain and justify that joke, by explaining how the education system is necessary and important, even if the Labyrinth isn’t a good or appropriate analogy for it (In terms of the Minotaur aspect; in terms of the inescapably complex maze, it is a perfect analogy. But if you don’t need the maze, if the purpose of the maze is not valid, there’s no reason to maintain the maze.) I sat down several times intending to look up the facts to support that argument.

But I always hit this wall. I know the reasons people argue for education. And I don’t believe them.

There is the aspect I mentioned at the beginning of this, and reference with my overwrought allusions. Education expands the mind, and expands the world. Even apart from the professions that require extensive specific knowledge — and ignoring the toxic narrow-minded view that education is intended primarily to promote economic outcomes — education gives people the ability to create and apply creativity; to identify, measure, and solve problems; to connect different ideas and areas of knowledge in order to gain new insight or create new things; to communicate and empathize with others; to dream and achieve those dreams. Without education, art becomes pale and shallow, and that’s a truly terrible loss. Without education, scientific and technological progress becomes impossible, and that’s — not necessarily all bad, but it does create the possibility for great suffering, if we don’t keep changing to match our changing world. Education is necessary for many people, for many reasons: and I don’t believe education itself is ever harmful.

But education is not the education system.

I do think the Minotaur/Labyrinth analogy is perfect from one perspective: mine. And those of people like me. Because like Minos, and unlike the Minotaur, we need the Labyrinth. I am a good teacher: largely because I work well within, and slightly in opposition to, the educational system. I make the classroom a comfortable place, I make it easier for my students to come to school and succeed and feel valued there. And that’s a good thing. I also teach literature and reading and writing and thinking well, and that’s a better thing. But the things that I teach don’t need to be taught within the system: I have thought often of how much I would love to be like Socrates, or one of the other ancient philosophers, simply declaiming and discussing in the public square, teaching anyone who wanted to learn. That would be so much better than requiring a classroom full of 15-year-olds to write a five-paragraph essay. But you see, I couldn’t make a living doing that. To make a living, I need the system. My other gifts as a teacher, the way I help my students survive through the trials and tribulations of the system — not only do I not need the system to provide support to people who might be struggling, but without the system, those people would not need me. To be meaningful, I need the system.

Basically, to deal with my own problems, I need to make sure other people have problems, too. And that’s Minos and the Minotaur and the Labyrinth. Let’s take note that, not only was the Minotaur captive in the Labyrinth, but Daedalus, the artificer who designed it, was also held captive by Minos; and the tribute of 14 youths who were fed to the Minotaur every year were sent by Athens because Minos defeated them in a war. None of those problems would have existed if Minos hadn’t created them.

And the same goes for the education system. I, like Minos, could make different choices, and live a different life; I don’t believe that teaching is literally the only thing I could do — for one thing, I’d make a hell of a therapist. So I don’t literally need the educational system, I simply benefit from its existence. Minos didn’t need the Labyrinth: he could (in theory) have made better choices in the first place, and never had the existence of the Minotaur to burden him; but if he did end up with the Minotaur, I bet there could be other solutions to the problem. First and foremost, the man lived on an island: surely there were other, smaller, islands nearby. Maybe he could have built a lovely little home for his man-eating stepson, far away from the people of Minos’s kingdom; finding food might still be an issue — but presumably the Minotaur didn’t have to kill what he ate, and dead people are not terribly hard to find. Within the context of an ancient civilization, the Minotaur would be a hell of a capital punishment for Minos to inflict on Cretan criminals.

So the truth is, we may not need the education system at all, other than as a way to maintain the lifestyles of people who are part of the system: and even as one of those people, I don’t believe that justifies the Labyrinth. It is unquestionably valuable and effective for millions of people, as I said; that may be enough benefit to make it worth keeping and trying to fix the flaws and failures that make it useless and even damaging to millions of others, and ideally to make it relevant to the countless people in the third group who just don’t need it. Education is good for all, and harmful for none; maybe we can make the system reflect that. But it is also possible that a wholly new system, or no system at all, in this age of available information and crowd-sourced instruction available to anyone with broadband, would work better for more people.

I’m going to endeavor to figure it out. That’s the long term goal of this series, of this blog. To decide whether or not we need the education system (And if we do, how to fix it), and whether or not we need to replace it.