A Walk in the Woods

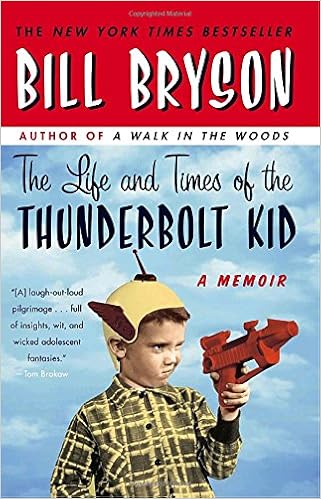

The Life and Times of the Thunderbolt Kid

by Bill Bryson

Bill Bryson and I have nothing in common.

Mr. Bryson has four children; I have three, but they have fur and feathers and shells. He moved to England after only a year in college, and spent the next twenty years or so in Europe; I haven’t been out of the United States since I was 13, and that was only for a week. He grew up in the 1950’s, when America was ostensibly at its peak; I grew up in the 70’s when America had disco. He grew up in, and has a deep nostalgic love for, the Midwest; I’m strictly coastal, and have never even driven through Iowa, where Bryson spent his entire childhood, in the same house in Des Moines. We are both the youngest, he of three and me of two, and we come from literary traditions: his parents were both journalists, his father one of the best sportswriters (Bryson the Younger tells us, but he has a valid argument) in the history of baseball; though neither of my parents are terribly literary, my grandmother and great-grandmother were both authors, teachers, and librarians. But of course, Bryson is an award-winning and best-selling author, and I just cracked 60 followers on my blog. (I thank and adore every one of you, don’t think I don’t.)

And perhaps most importantly, Bryson is a man who would, one, walk the Appalachian Trail, or at least a lengthy segment of it, and two, write a memoir about his American Heartland youth; and I am a man who would – read about both of those things.

Bryson’s writing is beautiful. This is why I keep reading his books, despite having no real common ground with him; this was never truer than with The Life and Times of the Thunderbolt Kid, when Bryson waxes poetic for nearly 300 pages about an America I know nothing about. I mean, he was the archetype: he loved baseball, did crappy in school, and had a freaking paper route, for the love of Clark Kent. Me? I played D&D and Nintendo. Hated sports. Straight A’s until I got to high school, when my grades slipped – to mostly B’s. (I did get a few D’s and F’s, and another thing Bryson and I had in common was a whole lot of truancy in high school.) He writes wonderfully about how simple and perfect was that world, a world I didn’t know and therefore don’t long for. And honestly, even Bryson’s excellent writing didn’t make me long for it. Even though the freedom of unsupervised playtime and the Golden Age of comic books do call to me, as do the unique character of a city made up entirely of local businesses, run by local people, catering to the specific needs and wants of their neighbors, whom they know personally: the department stores, the grocery stores, the restaurants, they all sound lovely indeed. But I don’t want ’em.

The same for the Appalachian Trail, the focus of A Walk in the Woods. I had two friends who walked the whole thing one college summer, and I have always envied them their experience; no more, man. No chance. I wouldn’t even do the abbreviated hike that Bryson writes about. He talks about the exhaustion, the misery, the crappy food, the monotony of the scenery, the irritating other hikers – even a little about the murders that were committed near where he was hiking while he was there, when two female hikers were killed on the trail. Never solved, at least not by the time Bryson wrote the book. It all adds up to a great big No Thanks: even with Bryson’s excellent descriptions of the glorious vistas, the fascinating (Seriously) history of the trail and the regions it meanders through, the sense of accomplishment so palpable you can feel it coming off the page.

Actually, I thought that was the best thing about both of these books: while Bryson does talk sincerely and at length about the good things about these two experiences, he doesn’t shy away from the negative side. His mother was a crappy cook, and that experience is made much worse by the total lack of culinary adventurousness of the era. His parents didn’t worry about anything, giving him great privacy and freedom – but they also painted everything with lead, asbestos, and radiation; Bryson lived through the end of the polio era, and in a time when people, who grew up in the Depression, were frequently missing limbs. In A Walk in the Woods, as I said, he goes through every painful, plodding step, making them even more vivid through the inclusion of his out-of-shape former-alcoholic friend Katz, who walks the trail with Bryson, but slower and with even more suffering. And that’s a lot of suffering.

You hear all about the bad parts, which really does serve to make the good parts seem more genuine and more warmly appreciated. It’s easy to understand how much Bryson loved his family’s unexpected road trip to a still-new Disneyland when he also talks about the usual family vacation to visit family that nobody wants to see, not even the family themselves. It’s easy to see how happy Bryson was to go home when he finished his Appalachian Trail hike when he takes you through every terrible day before that; it’s easy to see the beautiful woods he walks through when he talks about the rain and the mud and the cold.

So even though we’re nothing alike, and Bryson writes personal non-fiction, which should make it hard for me to relate to and understand his work, I am going to keep reading it: because Bryson is a hell of a writer, and he makes me like his books even if I doubt I would like him very much. Nothing personal, Bill. But thank you for everything personal you have shared with me. You keep writing it, and I’ll keep reading it.