I enjoy frequenting thrift stores — as who doesn’t? — and one of my favorite things to do is peruse the books, especially the older ones. This is not my wife’s favorite thing for me to do, so usually while I am geeking out over some 100-year-old grammar textbook (I swear one of these days I’m going to teach my class out of one of those and then WATCH OUT), she comes up behind me and says, “Are you ready?”

I am not. I am never ready to leave the books. I always want to spend more time looking at them. It’s a little frustrating because I don’t always want to spend as much time READING them, so they tend to pile up. (Another reason why my wife interrupts me, and she’s right to do it.) But my wife is right to interrupt me, so I say I am ready, and I leave. Usually without any books. Which is probably good, as they are often more curiosities than books I want to actually read and own.

But sometimes, when I am quick and lucky, I get to find something genuinely awesome. I have a collection of hundred-year-old romances by my favorite pirate author, Jeffery Farnol, some acquired at thrift stores and library book sales, which I am very proud of and love reading.

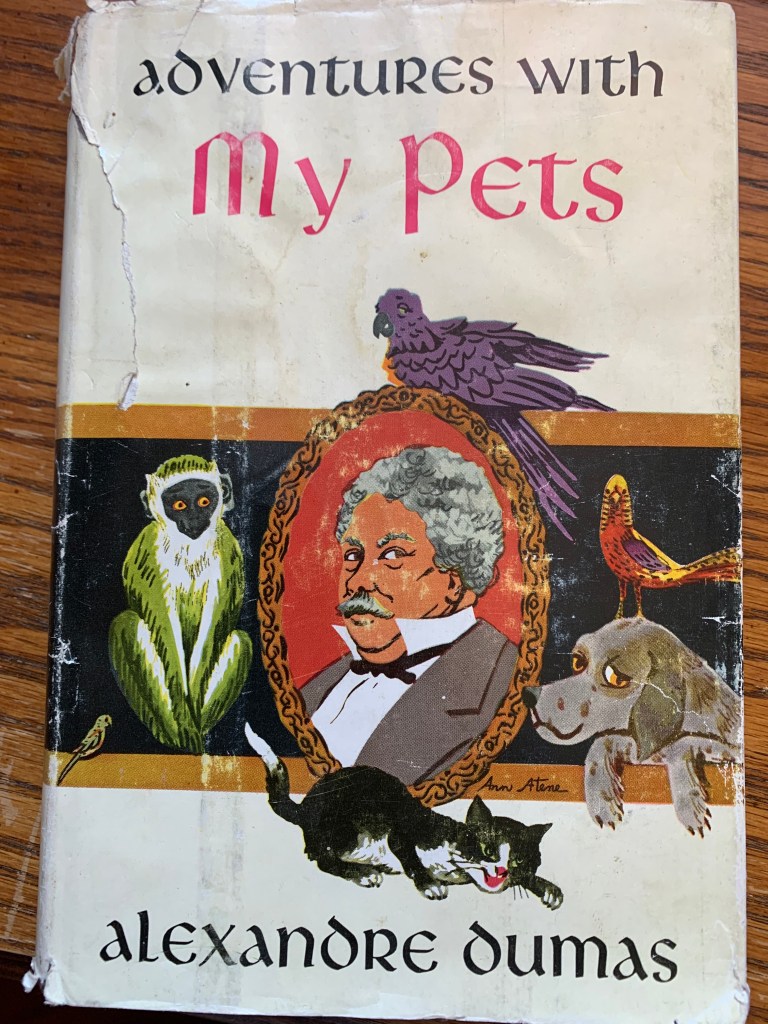

And a few months ago, at the local Human Society thrift store here in Tucson, I found — this.

This is a memoir written by the author of The Three Musketeers and The Count of Monte Cristo. Now, Dumas was a badass, particularly as a writer. I’ve read Monte Cristo, and it’s bloody brilliant; and pets are absolutely my thing — so I had to get this. Plus it was only $5.

Unfortunately, as Dumas lived in the 19th century, the times they have been a-changin’: and Dumas did not think of pets the same way that I do — and neither, honestly, did he think of adventures in the same way I do. I was hoping for, I dunno, hiking in beautiful mountains with dogs, who run off the trail and then make friends with an elk and bring it back to get a scratch behind the ear and take a treat from Dumas’s hand; that would be an adventure! With a pet!

Instead I got a whoooooooole lot of hunting. Dumas surely did like to shoot him some animals. Particularly rabbits and birds. The title, you see, comes from the fact that one of the main characters in the memoir is Dumas’s hunting dog, his English pointer Pritchard. And if you count all the times Dumas blasted a bunch of small helpless creatures with a shotgun while Pritchard pointed at them, then you betcha, there were plenty of adventures with his pets. But as you can probably tell, it was not my cup of tea.

It was interesting. Dumas was still a hell of a writer, and he does manage to make a lot of the little anecdotes come to life. Some of them were even fun: the man had a lot of pets, some of which he treated well; while many of Pritchard’s stories are about hunting, there is also one about how Pritchard often brought home many other dogs from the neighborhood to share in his lunch, because Dumas spoiled his animals and therefore Pritchard’s friends wanted the same good food he provided his dog. There are many conversations between people, often but not always about the animals, which were interesting and amusing. There’s a great secondary character, Michel, who was Dumas’s groundskeeper/animal expert, and he is interesting and amusing; Dumas presents a bunch of ridiculous folklore legends as coming from this guy, and clearly we’re supposed to laugh at them (there’s a chapter where Michel asserts that frogs act as midwives to other pregnant frogs, and so either frogs must have taught this to OBGYNs, or OBGYNs must have taught this to frogs — and as a fan of frogs, I’m good either way), but Dumas never makes Michel seem like a fool or a doofus, which I enjoyed. I appreciate that Dumas was, as he was described in one chapter, one of the most arrogant and self-centered of men (Which, not to be stereotypical, but I feel like saying that about a Frenchman is saying something) — but also one of the most generous and compassionate. He is completely ridiculous about handing out money left and right, usually, in this book, to acquire more animals, and I like that. I love the chapter where Dumas is described: because he reprinted a letter from a friend of his who defended him in Parisian social circles, with a letter to the local newspaper, which is fantastic; the letter basically says, Yes, he is arrogant, but also generous — and the real difference is, he’s arrogant because he actually is the greatest author in France, and that makes him a better person than all the rest of us.

I loved that.

But I did not enjoy all the killing of animals. I liked the cat Mysouff, but not when Mysouff killed all the pet birds. I liked the dog Mouton, but not when Dumas kicked Mouton in the rear, as hard as he could, for digging up his garden, and Mouton bit the crap out of Dumas’s hand — and the point of the story was that Dumas therefore had trouble writing for a while, because it was his right hand. I liked Pritchard, but not when Pritchard went hunting, or just killing and eating animals for fun — and especially not when Pritchard gets hurt and Dumas plays it basically for laughs: the dog gets shot by a hunter friend of Dumas’s, and the joke is that the pellets hit Pritchard in the testicles — but not to worry, one of the testicles is still functional! So all is well! And I was just like, “MOTHERFUCKER, SOMEONE SHOT YOUR FUCKING DOG, GO KILL HIS ASS!”

Plus: the dog dies in the end. And not of old age, surrounded by the family that loves him.

So nope: this was definitely not the book I was hoping for, and I would generally not recommend it. If you are a huge fan of Dumas, then you might enjoy it; it gives more insight into him and his lifestyle than it does into his pets or his attitudes towards his pets — but if you, like me, are a pet person, give this one a pass.