I keep not doing this: but I need to do this. Now, because there are always other things which I can write about, which I want to write about; this week I got into an incredibly stupid argument on Twitter, which is crying out for me to write a full-length takedown of my opponent; also, we had parent conferences, which opens up a couple of good discussions about students in general; also, I agreed to go to an AVID conference this summer, which means I can talk about AVID and conferences and so on; also, we had to pay money in taxes this year AND IT’S MY SCHOOL’S FAULT —

So there’s a lot I could write about.

But I need to write about this.

I already wrote about the beginning of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” but I didn’t write about the whole piece. Intentionally, because my essay was already too long, and the place where I stopped is important enough and valuable enough to receive the final emphasis of closing that piece with it; but now we need to talk about the rest of the piece, not least because it is still brilliant, nor only because it is still relevant to our society today, and the discourses we have around race and prejudice and equality and so on. Also because I said I would do this: and I need to keep my word.

So here we go again.

(One quick note: I have put some jokes in here, particularly in a couple of the links; I hope that doesn’t come across as too irreverent. Dr. King is and will always be one of my most idolized heroes. I just think that a little humor helps to get through an essay this long, with this much heavy subject matter. But I do apologize if any of the jokes hit a sour note.)

So the section I covered there goes to the end of the second page; I wonder how much of that length is intentional in that it seems like a piece that long and no longer could easily be reprinted in newspapers, but I don’t know. It also builds beautifully as an argument, leading to that conclusion. In any case, the next paragraph opens a new line of argument — though it is related, of course. This link shows another iteration of the letter, this one with a clear transition at this point, which I like.

YOU express a great deal of anxiety over our willingness to break laws. This is certainly a legitimate concern. Since we so diligently urge people to obey the Supreme Court’s decision of 1954 outlawing segregation in the public schools, it is rather strange and paradoxical to find us consciously breaking laws. One may well ask, “How can you advocate breaking some laws and obeying others?” The answer is found in the fact that there are two types of laws: there are just laws, and there are unjust laws. I would agree with St. Augustine that “An unjust law is no law at all.”

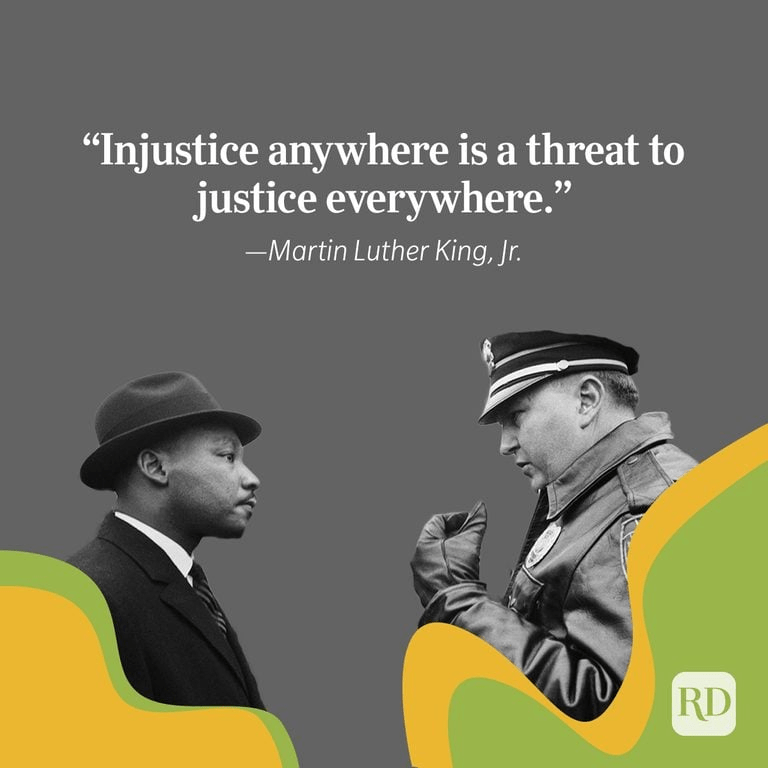

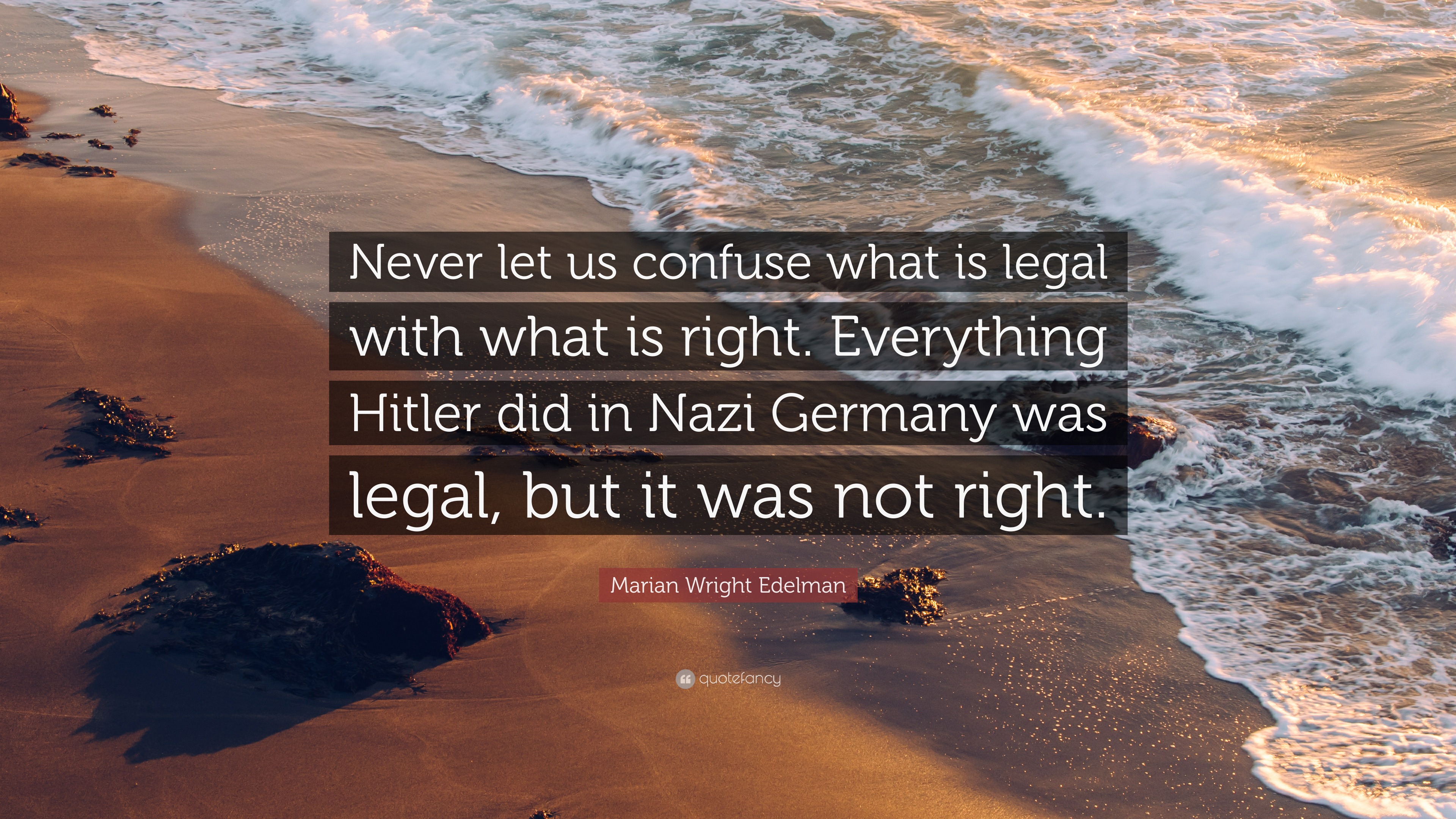

Notice that Dr. King continues the same tone and structure of argument, even after he has had this incredible cri de coeur about the African-American experience in the U.S.: he states their objection, and then turns it around on them. Willingness to break laws is a concern, you say? By gum, you’re right! You all should obey the Supreme Court’s decision to desegregate schools, shouldn’t you? But again, he offers this point about their hypocrisy in the politest possible way: by saying that it might be strange to see the civil rights activists doing the same apparently hypocritical thing, defending the law while breaking the law. But then he explains why the civil rights activists are not, in fact, doing anything hypocritical — and note that he uses “paradoxical” rather than the term “hypocritical:” because a paradox is only seemingly contradictory, generally from one perspective; there is another perspective by which it makes perfect sense (For instance, the paradox “To preserve peace, you must prepare for war.” It only seems like a contradiction; it actually makes perfect sense in a world where not everyone shares a desire for peace.): because there are two types of laws. King separates here the concept of “legal” from the concept of “just” — a distinction we point out again and again in our society.

And where does Dr. King get the justification for his distinction? Why from Saint Augustine: one of the most important and influential of all Christian thinkers. How you like them apples, Clergymen?

Continuing his explanation of the distinction between law and justice, Dr. King refers to the other most influential and important Christian thinker, St. Thomas Aquinas:

Now, what is the difference between the two? How does one determine when a law is just or unjust? A just law is a man-made code that squares with the moral law, or the law of God. An unjust law is a code that is out of harmony with the moral law. To put it in the terms of St. Thomas Aquinas, an unjust law is a human law that is not rooted in eternal and natural law. Any law that uplifts human personality is just. Any law that degrades human personality is unjust. All segregation statutes are unjust because segregation distorts the soul and damages the personality. It gives the segregator a false sense of superiority and the segregated a false sense of inferiority. To use the words of Martin Buber, the great Jewish philosopher, segregation substitutes an “I – it” relationship for the “I – thou” relationship and ends up relegating persons to the status of things. So segregation is not only politically, economically, and sociologically unsound, but it is morally wrong and sinful. Paul Tillich has said that sin is separation. Isn’t segregation an existential expression of man’s tragic separation, an expression of his awful estrangement, his terrible sinfulness? So I can urge men to obey the 1954 decision of the Supreme Court because it is morally right, and I can urge them to disobey segregation ordinances because they are morally wrong.

And yes: he also referred to Paul Tillich, one of the most influential Christian philosophers of the 20th century; and to Martin Buber, “the great Jewish philosopher.” (How you like them apples, Rabbi?) Let me emphasize here, if I didn’t do it enough before, that Dr. King wrote this letter in jail: without reference materials. He just knew all this stuff. (I mean, he did have a doctorate in systematic theology; and his dissertation was partly about Tillich’s work, so.) The only way to improve an ethos argument this strong, with references to authorities this relevant to both your point and your audience, is to show that you yourself are an authority to be reckoned with.

The argument itself is remarkable. He provides three different definitions of his distinction between just and unjust laws: first, a religious one — just laws square with the law of God (and note he includes non-religious people by also calling it “the moral law”, and then brings it back to religion and Aquinas by referring to the idea of laws “not rooted in eternal and natural law”); second, a psychological definition, saying that just laws uplift human personality and unjust laws degrade it; and third, Buber’s philosophical concept of the “I-it” relationship replacing the “I-thou” relationship, turning people into objects. Into things. And look at the use of parallelism here: three reasons why segregation is unsound, followed by another way that it is wrong (and adding the idea that segregation is sinful”; three different ways that segregation is an expression of man’s evil; and a juxtaposition of two antithetical examples that match King’s categories: one just law, and one unjust law.

Then, if that isn’t enough ways to help his audience understand this concept , King gives us this next paragraph:

Let us turn to a more concrete example of just and unjust laws. An unjust law is a code that a majority inflicts on a minority that is not binding on itself. This is difference made legal. On the other hand, a just law is a code that a majority compels a minority to follow, and that it is willing to follow itself. This is sameness made legal.

That’s right, a more concrete definition, with another simple summative way to understand it: difference made legal, and sameness made legal. He’s right: this is more concrete, and has none of the religious overtones of the last paragraph — but it makes just as much sense, and is just as sound. Have we got enough ways to understand this now? Of course we do.

And then he adds another one:

Let me give another explanation. An unjust law is a code inflicted upon a minority which that minority had no part in enacting or creating because it did not have the unhampered right to vote. Who can say that the legislature of Alabama which set up the segregation laws was democratically elected? Throughout the state of Alabama all types of conniving methods are used to prevent Negroes from becoming registered voters, and there are some counties without a single Negro registered to vote, despite the fact that the Negroes constitute a majority of the population. Can any law set up in such a state be considered democratically structured?

Here Dr. King brings in another issue: voting rights. How can a law be democratic when the people were not capable of opposing nor supporting its passage, because of the suppression of their rights and their franchise? The argument is so plain and irrefutable that he doesn’t even bother to answer his rhetorical question. Instead, perhaps feeling understandably bitter as he sits in a jail cell writing about justice and injustice, Dr. King moves to one other complexity in the distinction between legal and just: when the application of a law makes it unjust. And I say he might have been bitter because his example is once again his own, talking about the city of Birmingham’s use of a parade permit ordinance to remove the civil rights activists’ First Amendment rights.

These are just a few examples of unjust and just laws. There are some instances when a law is just on its face and unjust in its application. For instance, I was arrested Friday on a charge of parading without a permit. Now, there is nothing wrong with an ordinance which requires a permit for a parade, but when the ordinance is used to preserve segregation and to deny citizens the First Amendment privilege of peaceful assembly and peaceful protest, then it becomes unjust.

Then he goes on to compare Birmingham first to three villains from history, and himself and his allies to the heroes who were suppressed by the villains — and then Dr. King confirms Godwin’s Law (Within a different context), while breaking the corollary to Godwin’s Law. Because Dr. King brings up Adolf Hitler. And THEN he throws in Stalin and Communism: it’s like the perfect American argument, here. Note that the three villains and heroes he mentions before going to the Nazis are both religious and political: Nebuchadnezzar, the Babylonian king who tried to kill the three Jewish prophets Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego (I’M SORRY DR. KING I HAVE TO) in the Old Testament; the Romans, who tried to suppress Christianity with various atrocities; and the elite of Athens, who executed Socrates for teaching the truth. Note also that all three villains lost these fights.

Which side is Dr. King’s? Which side would you rather be on?

Of course, there is nothing new about this kind of civil disobedience. It was seen sublimely in the refusal of Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego to obey the laws of Nebuchadnezzar because a higher moral law was involved. It was practiced superbly by the early Christians, who were willing to face hungry lions and the excruciating pain of chopping blocks before submitting to certain unjust laws of the Roman Empire. To a degree, academic freedom is a reality today because Socrates practiced civil disobedience.

We can never forget that everything Hitler did in Germany was “legal” and everything the Hungarian freedom fighters did in Hungary was “illegal.” It was “illegal” to aid and comfort a Jew in Hitler’s Germany. But I am sure that if I had lived in Germany during that time, I would have aided and comforted my Jewish brothers even though it was illegal. If I lived in a Communist country today where certain principles dear to the Christian faith are suppressed, I believe I would openly advocate disobeying these anti-religious laws.

Once again, Dr. King has made an argument so strong, so irrefutable at this point, after he has given so many different ways to understand it, and so many different reasons to accept it, that I really can’t fathom why people still don’t agree with this argument. Except for those who haven’t read it, of course.

The next part of King’s letter brings up the element that my brother, when I mentioned that I had written an essay about Dr. King, used to identify the Letter from Birmingham Jail as distinct from Dr. King’s other masterworks: “Ohhh,” he said to me on the phone when I was trying to tell him which piece I had analyzed, “is that the one with the white moderates?”

Yes it is.

I MUST make two honest confessions to you, my Christian and Jewish brothers. First, I must confess that over the last few years I have been gravely disappointed with the white moderate. I have almost reached the regrettable conclusion that the Negro’s great stumbling block in the stride toward freedom is not the White Citizens Councillor or the Ku Klux Klanner but the white moderate who is more devoted to order than to justice; who prefers a negative peace which is the absence of tension to a positive peace which is the presence of justice; who constantly says, “I agree with you in the goal you seek, but I can’t agree with your methods of direct action”; who paternalistically feels that he can set the timetable for another man’s freedom; who lives by the myth of time; and who constantly advises the Negro to wait until a “more convenient season.” Shallow understanding from people of good will is more frustrating than absolute misunderstanding from people of ill will. Lukewarm acceptance is much more bewildering than outright rejection.

He confesses: and then he destroys us with his disappointment. This part of the essay I have trouble reading and teaching; not because it’s too complicated, or too upsetting in its language and images (as some of my students find the Perfect Sentence I wrote about in the first post) — but because it’s true, and it’s me. I am a White moderate. I mean, I’m pretty goddamn liberal — but also, I don’t act in order to achieve a more just society; I simply support the cause. It’s not entirely me, because I don’t object to the methods used by those who are more active in pursuing our common goal; but it’s me because I don’t participate in those methods.

King here juxtaposes this critique of people who support the cause but not enough, with those who oppose the cause though they claim to be understanding of it: the Clergymen. No White moderates, those Alabamians; they seem like pretty rock-ribbed conservatives, fitting perfectly into the mold of paternalistic White leaders whom King refers to above, as they compliment “their” [“our”] Negro community for keeping the peace, which is exactly what King is taking issue with. But he does it in such an incredible way:

In your statement you asserted that our actions, even though peaceful, must be condemned because they precipitate violence. But can this assertion be logically made? Isn’t this like condemning the robbed man because his possession of money precipitated the evil act of robbery? Isn’t this like condemning Socrates because his unswerving commitment to truth and his philosophical delvings precipitated the misguided popular mind to make him drink the hemlock? Isn’t this like condemning Jesus because His unique God-consciousness and never-ceasing devotion to His will precipitated the evil act of crucifixion? We must come to see, as federal courts have consistently affirmed, that it is immoral to urge an individual to withdraw his efforts to gain his basic constitutional rights because the quest precipitates violence. Society must protect the robbed and punish the robber.

That’s right: not only does King compare himself, for the third time, to Socrates — now he actually compares himself to Jesus. And, of course, he’s right: blaming the victims of oppression for inciting the violence of the oppressors is precisely like blaming Jesus for making the Romans crucify him. And who does that in the story of the Passion?

Why, this guy, of course.

In the next paragraph, King jumps back to the White moderates, connecting the two not only with their half-hearted support or opposition to King’s cause, but with a parallel to the teachings and goals of the Church:

I had also hoped that the white moderate would reject the myth of time. I received a letter this morning from a white brother in Texas which said, “All Christians know that the colored people will receive equal rights eventually, but is it possible that you are in too great of a religious hurry? It has taken Christianity almost 2000 years to accomplish what it has. The teachings of Christ take time to come to earth.” All that is said here grows out of a tragic misconception of time. It is the strangely irrational notion that there is something in the very flow of time that will inevitably cure all ills. Actually, time is neutral. It can be used either destructively or constructively. I am coming to feel that the people of ill will have used time much more effectively than the people of good will. We will have to repent in this generation not merely for the vitriolic words and actions of the bad people but for the appalling silence of the good people. We must come to see that human progress never rolls in on wheels of inevitability. It comes through the tireless efforts and persistent work of men willing to be coworkers with God, and without this hard work time itself becomes an ally of the forces of social stagnation.

By putting these two groups, White moderates who say they support civil rights but oppose the methods used by the activists, and the Alabama clergymen who say they understand the desires of African-Americans for freedom but show they really would rather maintain the status quo of segregation and oppression, in such close parallel, switching back and forth with what almost seems a complete lack of connecting transitions between subjects, King achieves his goal: he shows that these groups are essentially the same. There is what they say, and then there is what they do: and their actions speak louder than their words. He is thus chastising both groups, by comparison to each other: the clergymen are no better than Northern White moderates, synonymous in the South with lying hypocrisy; and the White moderates are no better than White Southerners: synonymous with racist oppressors. Neither group is willing to be coworkers with God: they are the forces of social stagnation which the coworkers with God oppose.

(Okay, I don’t think that’s me any more. Though I still worry that I would disappoint Dr. King.)

Dr. King’s next argument has to do with “extremism.”

YOU spoke of our activity in Birmingham as extreme. At first I was rather disappointed that fellow clergymen would see my nonviolent efforts as those of an extremist. I started thinking about the fact that I stand in the middle of two opposing forces in the Negro community. One is a force of complacency made up of Negroes who, as a result of long years of oppression, have been so completely drained of self-respect and a sense of “somebodyness” that they have adjusted to segregation, and, on the other hand, of a few Negroes in the middle class who, because of a degree of academic and economic security and because at points they profit by segregation, have unconsciously become insensitive to the problems of the masses. The other force is one of bitterness and hatred and comes perilously close to advocating violence. It is expressed in the various black nationalist groups that are springing up over the nation, the largest and best known being Elijah Muhammad’s Muslim movement. This movement is nourished by the contemporary frustration over the continued existence of racial discrimination. It is made up of people who have lost faith in America, who have absolutely repudiated Christianity, and who have concluded that the white man is an incurable devil. I have tried to stand between these two forces, saying that we need not follow the do-nothingism of the complacent or the hatred and despair of the black nationalist. There is a more excellent way, of love and nonviolent protest. I’m grateful to God that, through the Negro church, the dimension of nonviolence entered our struggle. If this philosophy had not emerged, I am convinced that by now many streets of the South would be flowing with floods of blood. And I am further convinced that if our white brothers dismiss as “rabble-rousers” and “outside agitators” those of us who are working through the channels of nonviolent direct action and refuse to support our nonviolent efforts, millions of Negroes, out of frustration and despair, will seek solace and security in black nationalist ideologies, a development that will lead inevitably to a frightening racial nightmare.

Specifically, King is replying to this sentence in the Statement: “We do not believe that these days of new hope are days when extreme measures are justified in Birmingham.” (Blogger’s Note: Since I did that to them, I’m going to do this to Dr. King’s words: “We must come to see that human progress never rolls in on wheels of inevitability.“) This line clearly pissed King off: but more important, it’s an idea that he can’t allow to shape the narrative. So as he does with so many other parts of the Statement’s argument, he smashes this again, and again, and again. He shows the two extremes in the African-American community: one extreme is those African-Americans who have been worn down by the oppression that has defined their lives; and the other is — Malcolm X. King doesn’t name the other man, with whom he was so often presented in juxtaposition as two opposites, the moderate and the extremist; but he doesn’t have to. Elijah Muhammad (Himself no moderate) and his Nation of Islam are synonymous with Malcolm X, and though King and X were a hell of a lot closer in a lot of ways than most people thought or said, it is exactly these kinds of people, these southern Clergymen, who would have used King as an example of a better leader, a more reasonable leader, than X, because King used non-violence while Malcolm X talked about violence. I suspect this comparison and the implication that King was softer and more accommodating to the oppressors’ status quo, made the man angry: and so the description at the end of this paragraph — a fine example of Dr. King showing that he did not believe that non-violence was the only way to achieve freedom: just that it was the best way, as it would not lead to “floods of blood.” If the warning is not clear, he reiterates it in the next paragraph:

Oppressed people cannot remain oppressed forever. The urge for freedom will eventually come. This is what has happened to the American Negro. Something within has reminded him of his birthright of freedom; something without has reminded him that he can gain it. Consciously and unconsciously, he has been swept in by what the Germans call the Zeitgeist, and with his black brothers of Africa and his brown and yellow brothers of Asia, South America, and the Caribbean, he is moving with a sense of cosmic urgency toward the promised land of racial justice. Recognizing this vital urge that has engulfed the Negro community, one should readily understand public demonstrations. The Negro has many pent-up resentments and latent frustrations. He has to get them out. So let him march sometime; let him have his prayer pilgrimages to the city hall; understand why he must have sit-ins and freedom rides. If his repressed emotions do not come out in these nonviolent ways, they will come out in ominous expressions of violence. This is not a threat; it is a fact of history. So I have not said to my people, “Get rid of your discontent.” But I have tried to say that this normal and healthy discontent can be channeled through the creative outlet of nonviolent direct action. Now this approach is being dismissed as extremist. I must admit that I was initially disappointed in being so categorized.

But as I continued to think about the matter, I gradually gained a bit of satisfaction from being considered an extremist. Was not Jesus an extremist in love? — “Love your enemies, bless them that curse you, pray for them that despitefully use you.” Was not Amos an extremist for justice? — “Let justice roll down like waters and righteousness like a mighty stream.” Was not Paul an extremist for the gospel of Jesus Christ? — “I bear in my body the marks of the Lord Jesus.” Was not Martin Luther an extremist?– “Here I stand; I can do no other so help me God.” Was not John Bunyan an extremist? — “I will stay in jail to the end of my days before I make a mockery of my conscience.” Was not Abraham Lincoln an extremist? — “This nation cannot survive half slave and half free.” Was not Thomas Jefferson an extremist? — “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal.” So the question is not whether we will be extremist, but what kind of extremists we will be. Will we be extremists for hate, or will we be extremists for love? Will we be extremists for the preservation of injustice, or will we be extremists for the cause of justice?

(Note on the text: the iteration of the Letter I have been pulling from separates this into two paragraphs. This one doesn’t. I think it should be one paragraph.)

This is another of my favorite arguments, and not least because King again compares himself to Jesus Christ — and also to Abraham Lincoln and Thomas Jefferson, along with the Jewish and Christian luminaries Amos, St. Paul, Martin Luther, and John Bunyan. (Also I love that he drops his namesake in there without even batting an eye — and don’t forget that the vast majority of Southern White Christian racists were of Protestant denominations). I also love the rapid-fire call-and-response of rhetorical questions with direct quotations that serve both as answers and as proof, while making use of all of the poetry in these various wonderful statements, and also showing off, again, King’s own erudition and understanding of the power of the right word at the right time for the right reason. And then those final rhetorical questions, with the explicit use of “we” inviting the audience — the White moderate, the White Southern clergyman, and every single person who ever reads this letter, including me and including you — to come up with our own perfect words, our own response to this call. What will we do? What kind of extremist will we be?

After this King closes his criticism of White moderates with the most terrible form of the guilt-imposing “I’m not mad, I’m just disappointed” position that he is using here: the “Maybe I expected too much of you.”

I had hoped that the white moderate would see this. Maybe I was too optimistic. Maybe I expected too much. I guess I should have realized that few members of a race that has oppressed another race can understand or appreciate the deep groans and passionate yearnings of those that have been oppressed, and still fewer have the vision to see that injustice must be rooted out by strong, persistent, and determined action.

Look at that. Look at it! “I guess I should have realized?” GodDAMN, sir. I would like to personally apologize for everyone and everything, ever. He does lighten the load slightly by naming a number of White activists, primarily reporters who had given fair or even favorable coverage to the Civil Rights movement, and thanking them for their contribution. Which makes me feel a tiny bit better because I’m writing this. But I’m still sorry, sir. I have eaten the plums that were in the icebox, the ones you were saving.

This next part, though? I got nothing but smiles for this. Because then he goes after the church.

Honestly, I’m going to skip over this, because this is not my area. I have not attended church since around about 1986, and my personal animus for religion would color my analysis of this too much. I want to pick out every single detail where King tells his fellow clergymen that the White church has let him down, and highlight every one, like some kind of manic hybrid of a mother-in-law and Vanna White, finding every single possible fault and holding it up for the audience to observe, while I smile from ear to ear. But I won’t do that. I will just point out that he specifically mentions one of the Eight Clergymen, Reverend Earl Stallings, for his action in allowing Black worshippers into his church without segregating them; this seems to me like a direct response and even challenge to the passive aggressive way the Clergymen never name Dr. King, even though EVERYBODY FUCKING KNOWS THAT’S WHO THEY MEANT. “Outside agitators,” my ass. I still recommend reading the entire letter, including this section; but here I’m just going to post his conclusion, because it’s so damn beautiful.

I hope the church as a whole will meet the challenge of this decisive hour. But even if the church does not come to the aid of justice, I have no despair about the future. I have no fear about the outcome of our struggle in Birmingham, even if our motives are presently misunderstood. We will reach the goal of freedom in Birmingham and all over the nation, because the goal of America is freedom. Abused and scorned though we may be, our destiny is tied up with the destiny of America. Before the Pilgrims landed at Plymouth, we were here. Before the pen of Jefferson scratched across the pages of history the majestic word of the Declaration of Independence, we were here. For more than two centuries our foreparents labored here without wages; they made cotton king; and they built the homes of their masters in the midst of brutal injustice and shameful humiliation — and yet out of a bottomless vitality our people continue to thrive and develop. If the inexpressible cruelties of slavery could not stop us, the opposition we now face will surely fail. We will win our freedom because the sacred heritage of our nation and the eternal will of God are embodied in our echoing demands.

“We were here.” I love that. “Our destiny is tied up with the destiny of America.” Just incredible.

At this point, having made all of his arguments, he’s almost — no, wait, he’s not done. He has one more thing to say.

I must close now. But before closing I am impelled to mention one other point in your statement that troubled me profoundly. You warmly commended the Birmingham police force for keeping “order” and “preventing violence.” I don’t believe you would have so warmly commended the police force if you had seen its angry violent dogs literally biting six unarmed, nonviolent Negroes. I don’t believe you would so quickly commend the policemen if you would observe their ugly and inhuman treatment of Negroes here in the city jail; if you would watch them push and curse old Negro women and young Negro girls; if you would see them slap and kick old Negro men and young boys, if you would observe them, as they did on two occasions, refusing to give us food because we wanted to sing our grace together. I’m sorry that I can’t join you in your praise for the police department. It is true that they have been rather disciplined in their public handling of the demonstrators. In this sense they have been publicly “nonviolent.” But for what purpose? To preserve the evil system of segregation. Over the last few years I have consistently preached that nonviolence demands that the means we use must be as pure as the ends we seek. So I have tried to make it clear that it is wrong to use immoral means to attain moral ends. But now I must affirm that it is just as wrong, or even more, to use moral means to preserve immoral ends.

I wish you had commended the Negro demonstrators of Birmingham for their sublime courage, their willingness to suffer, and their amazing discipline in the midst of the most inhuman provocation. One day the South will recognize its real heroes. They will be the James Merediths, courageously and with a majestic sense of purpose facing jeering and hostile mobs and the agonizing loneliness that characterizes the life of the pioneer. They will be old, oppressed, battered Negro women, symbolized in a seventy-two-year-old woman of Montgomery, Alabama, who rose up with a sense of dignity and with her people decided not to ride the segregated buses, and responded to one who inquired about her tiredness with ungrammatical profundity, “My feets is tired, but my soul is rested.” They will be young high school and college students, young ministers of the gospel and a host of their elders courageously and nonviolently sitting in at lunch counters and willingly going to jail for conscience’s sake. One day the South will know that when these disinherited children of God sat down at lunch counters they were in reality standing up for the best in the American dream and the most sacred values in our Judeo-Christian heritage.

He leaves this until the end. He knows that this is the one part of this letter most likely to anger his readers, because he is here criticizing the police — and even now, 60 years later (And please note that this April will be the 60th anniversary of this whole ordeal), I think we all know what happens to people who criticize the police. But he can’t not say this. He doesn’t have proof, not that the Clergymen or the White readership at large will accept — it is only the word of the arrested activists; nobody was there with a cell phone to record this scene — and you can see his bitter acknowledgement of the superficial truth of what the Clergymen said, that the police have been “rather disciplined in their public handling of the demonstrators.” Though even there, look at the use of the phrase “rather disciplined,” instead of the words “calm” and “restraint” which the Clergymen used. Notice the emphasis on “public,” immediately contradicted by the word “handling,” with its implication of manhandling, echoed in the word “disciplined,” with its sense of harsh control and even physical punishment. But of course, because he is Dr. Martin Luther King, he immediately shows how this example is the precise opposite of the “nonviolent” label the police might claim: because they are pursuing immoral ends. And they are contrasted against the truly nonviolent protestors and pioneers, who use genuine nonviolence to promote moral ends of justice — “the best in the American dream and the most sacred values in our Judeo-Christian heritage.” And since this comes here, at the very end, it has extra weight — I do think the overall length of this letter does make this seem more like a postscript than a strong conclusion; I think the passage I quoted above, at the end of the section about the church, is the real conclusion — but this is one final blow that is impossible to ignore. But of course, the police do not get the last word: that goes to the real heroes of the South, James Meredith, and Rosa Parks, and all of the people who fought alongside Dr. King for freedom. I, for one, would like to thank them all for their courage and their honor and their sacrifice.

Speaking of postscripts — and of too-lengthy writings, which need to finally be brought to a close — let me just end with the saltiest “Yours truly” in the history of letters:

If I have said anything in this letter that is an understatement of the truth and is indicative of an unreasonable impatience, I beg you to forgive me. If I have said anything in this letter that is an overstatement of the truth and is indicative of my having a patience that makes me patient with anything less than brotherhood, I beg God to forgive me.

Because in the end, even though the accusation that the civil rights movement and Dr. King were “impatient,” were “unwise and untimely,” was entirely false and absurd — it would be much, much worse if Dr. King were too patient.

And now, Dr. King’s actual “Yours truly,” which I would humbly like to echo myself, to everyone who reads this.

Yours for the cause of Peace and Brotherhood