I want to write about the AP exam I scored. But those scores haven’t been released yet, and neither have the examples and so on, which show how the scores were earned; and I don’t want to get in trouble for posting confidential material.

So, without going into too much detail about the exam or the prompt or how a student earned a specific score, I’m going to talk about one general aspect of the exam which I noticed this year more than most: terminology.

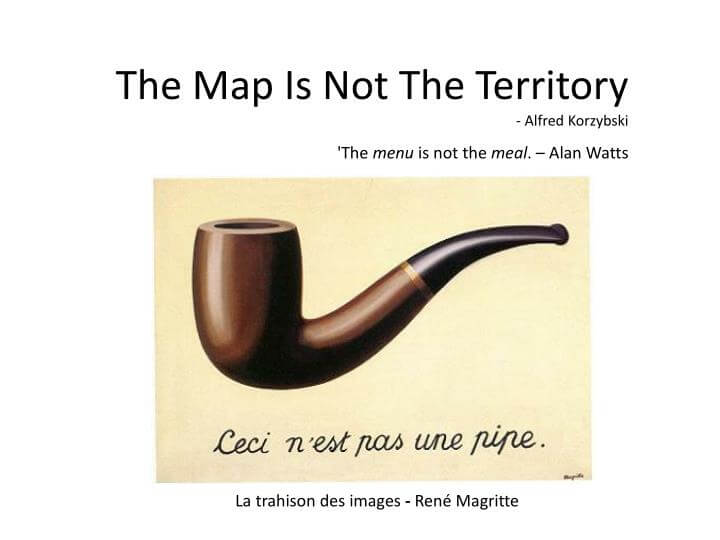

In keeping with the theme I seem to have established of talking about my dad, and also of using quotations to center and introduce my thoughts, here is one of my dad’s all-time favorite quotes:

“The map is not the territory, the word is not the thing itself.”

This is from the science fiction novel, The World of Null-A, by A.E. van Vogt. It hasn’t been turned into a meme on the internet — so I’m going to put the cover of the novel here, because it’s awesome.

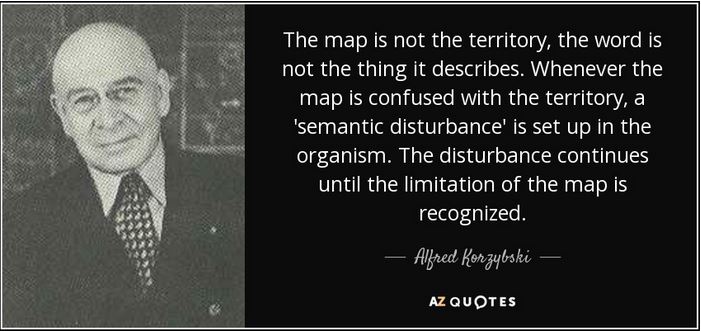

The quote is slightly adapted from a statement originally from Alfred Korzybski, a Polish-American philosopher and engineer, and while van Vogt’s words have not been memed, Korzybski’s have been.

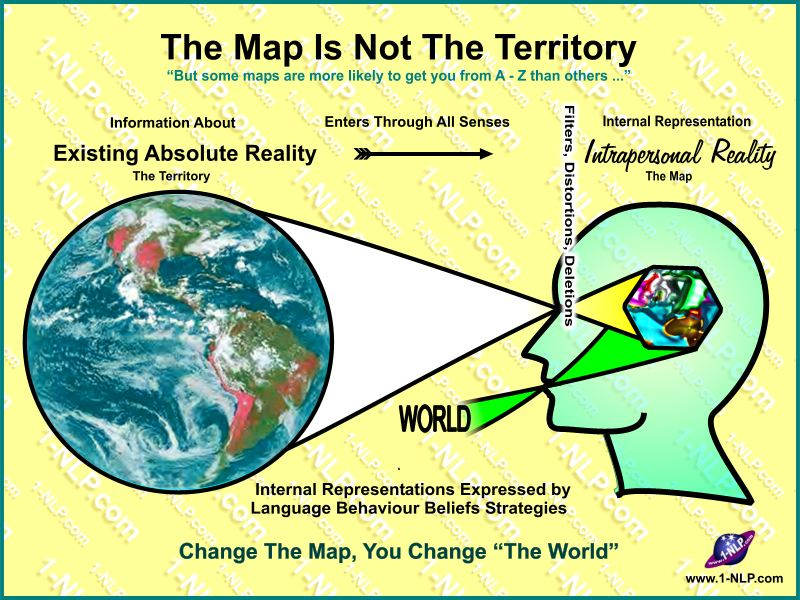

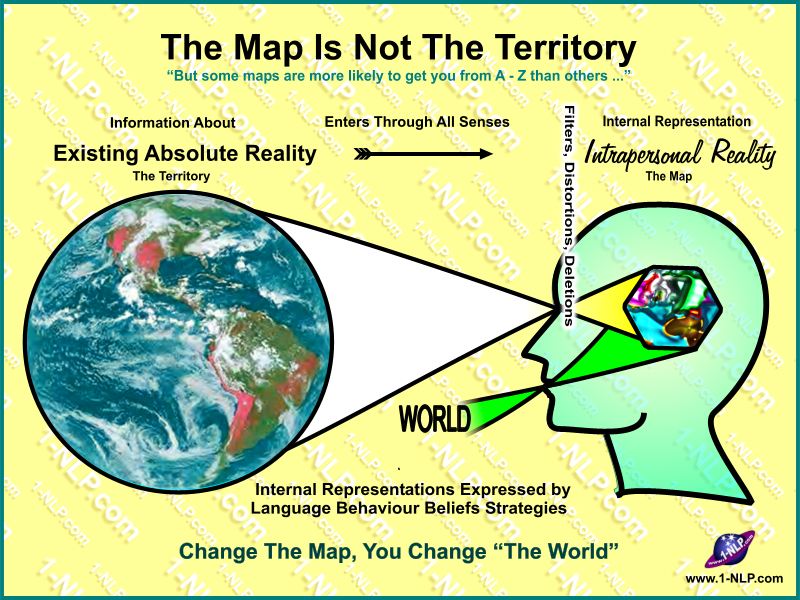

That’s the full quote, and you can see how quickly it makes one’s eyes cross. Here it is made even more confusing by the visuals:

But that’s okay, here’s the simpler version, complete with standardized background image:

But really, I prefer this last version, because I also like Watts’s iteration of this — and I love Rene Magritte.

So the point of this, then, is to recognize the limitations of representation and image — and of language itself. The map is probably the best example, because a map always sacrifices detail for coverage, showing a greater area while not showing everything about that area. If a map showed every detail of the area it depicted, it would be a photograph, not a map — and its value would be limited.

(Though it might be funny sometimes.)

On some level, this shows the difference between “book knowledge” and “world knowledge” — which my students still, still, call “street smarts,” a perfect example of a name that has lasted despite its limitations, which makes it a perfect example of the second half of this statement. If you know the name of a thing, that is analogous to “book knowledge;” and if you understand the thing (which is where I think the quote is going here, to a point about understanding, because certainly with a concrete object there is no doubt that the word could be the thing itself: I’m not sitting in the word “chair” right now.), that is equivalent to the experiential and deeper understanding implied by “street smarts.” Knowing the name for something does not mean you understand that thing, because the word is not the thing itself; again like the map, words reduce specific details in order to gain another value — generally universality, and economy, meaning I can communicate a fair amount of information, to a lot of people, without too many words. If I say I own a black SUV, then you don’t have much detail about my car — but (if you speak English) you have a general understanding of the category of vehicle to which my car belongs, and a general idea of its size and shape and appearance and so on, because we understand what aspects are included in the category “SUV,” and we know the color “black.” Also, as my wife has pointed out many times, with steadily growing annoyance as each year passes, all SUVs look the same — and a large proportion of them are black. But that means, while you can get a general idea of many, many cars with just two words, you can’t really identify those specific cars very well. And you definitely don’t know the things that make my car special, that make my car into my car. Not terribly important to understand the special things about my car, of course; but if you want to understand a person, you need to know much more than their name.

This comes into focus with the AP exam because I teach my students that they don’t really need to know the name of what they are talking about: but they need to understand the thing. This is, clearly, not how all AP teachers instruct their students, because I had MANY essays that used vocabulary the student did not really understand: and it showed. They named things they didn’t really have, because they didn’t understand the thing named. So that I don’t do that, to explain the details lacking in the term “AP exam,” so that you have more understanding of this thing instead of just knowing the name, the essay I scored last month was for the AP Language and Composition exam, which focuses on non-fiction writing, and examines primarily rhetoric. “Rhetoric” is another good example of a word which people know and use without really understanding it, because the connotations of the word have changed; now it mostly comes in a phrase like “empty rhetoric,” and is used to describe someone — usually a politician — who is speaking insincerely, just paying lip service to some idea or audience, without saying anything of substance; or in more extreme cases, using words to lie and manipulate their audience for a nefarious purpose. My preferred definition of rhetoric, the one I teach my students, is: “Using language to achieve a purpose.” What I am doing now in this blog is rhetorical: I am choosing words and using examples that I think will achieve my purpose — in this case to explain my idea, and to a lesser extent, to convince my audience that I am correct in my argument: that knowing the name of a thing is less important than understanding the actual thing.

So in the AP exam on Language and Composition, which focuses on rhetoric — or understanding and explaining how a speaker or writer uses language to achieve their purpose, as when a politician tries to convince an audience to vote for him or her — there are 50 or so multiple choice questions, and three essay questions. This year I scored the second essay question, which is the Rhetorical Analysis question; for this year’s exam (This is not privileged information, by the way; the questions were released right after the exam in May. It’s the answers that are still secret.) they used a commencement speech given at the University of Virginia at Charlottesville by former U.S. poet laureate Rita Dove. The goal of the essay was to “Write an essay that analyzes the rhetorical choices Dove makes to deliver her message about what she wishes for her audience of graduating students.”

Interestingly enough, the AP exam writers have given hints to the students in this instruction, which I’ve taken from the exam. They generally give important context in their instructions, quite intentionally; it’s easier to analyze rhetoric if you understand the context in which the speech or writing was delivered, so knowing that this speech was given at a commencement, at a university, in 2016, gives you a better idea of what is going to be said in the speech — you get the general shape of what is included in the thing named “commencement address.” One of the key aspects of this speech by Dove is both the expectation of what is included in a commencement address, and how she subverts that expectation: and that centers around the term “wish.” That’s the hint in the instruction there, along with the buzzwords “message” and “audience,” which are commonly part of a study of rhetoric and of rhetorical analysis.

Okay, that wasn’t interesting. I’ve lost you here, I realize. Let me use fewer words and just give you the general gist of my point: when students were analyzing Dove’s rhetoric, they did much better if they explained what she was doing and why, but didn’t know the proper name for her strategy; some of them knew the name of the strategy — or of a strategy — but couldn’t really explain it. They had the name, but not the thing itself.

Partly that’s because the study of rhetoric is very old, and thus has an enormous amount of terminology attached to it: much of it based on Latin and Greek roots, which makes the words sound really smart to modern speakers and readers of American English. It’s cool to use the words “antithesis” and “juxtaposition” and “zeugma,” so students remember the words and use them for that reason. I think it is also partly because a number of AP classes focus on remembering the word for something, rather than knowing the thing itself, because lists of words are easier to teach and easier to memorize and easier to test. Partly it’s because students under pressure try to impress teachers with the things they can do, to dazzle us and make us not notice the things they can’t do — like actually explain the thing they named.

Again, I don’t want to get into too many specifics on this particular essay because it hasn’t been released yet and I don’t want to get in trouble, so let me just give general examples.

There’s a rhetorical device called “polysyndeton.” (Cool name, isn’t it? Little annoying that the two y‘s are pronounced differently…) It means the use of more conjunctions than would be strictly necessary for grammar. If I listed all of my favorite activities and I said, “I love reading and writing and music and games and spending time with my pets and eating delicious food and taking walks with my wife,” that would be an example of polysyndeton. And if you were writing an essay about my rhetoric (Please don’t), you could certainly say that I used polysyndeton, and quote that sentence as an example. And if you used that sentence, it would be a correct example, and the person scoring your essay would recognize that you know what polysyndeton is, and you correctly defined and identified it, which is surely worth some points. Right?

But what does polysyndeton do? What did I do when I wrote the sentence that way, instead of, for instance, “I love reading, writing, music, games, spending time with my pets, eating delicious food, and taking walks with my wife.”? The ability to understand that, and to explain that — and, most importantly for the AP exam and for rhetorical analysis, the ability to explain how the effect I achieved through the use of polysyndeton helps to deliver my message, to achieve my purpose — that’s what matters. Not knowing the name.

(It’s a bad example here, by the way, because I made up the sentence just to show what the word meant, so it isn’t really part of my larger purpose; the purpose of using polysyndeton there was just to show what the hell polysyndeton is. And sure, I guess it was effective for that.)

The worst offenders here, on this year’s exam as in most, are the terms logos, pathos, and ethos, which are words used to describe certain kinds of argument, and also certain aspects of rhetoric. The words are Greek, and were chosen and defined by Aristotle; most rhetoric teachers at least mention them, usually, I imagine, as a way to show that there are many different ways to win an argument and to persuade an audience. That’s why I mention them in my class. But while a lot of students know the words, they don’t understand the thing itself, and so they find items in a passage they’re analyzing that looks like it belongs in one of those categories. Like statistics, which they identify as logos arguments, meaning arguments that appeal to reason and logic, which is indeed one way that statistics can be used. Dove uses a statistic in her speech, and a raft of student writers identified that as an instance of logos. The problem is that it isn’t logos, partly because it’s not a real statistic — she uses the phrase “150% effort,” and at one point lowers that to “75% effort” and “50% effort;” but at no time is she trying to present a reasoned and logical argument through the use of those numbers, which of course don’t come from any study or anything like that — and even more, because she’s not really trying to persuade her audience.

She was telling her audience an anecdote. And that’s where I ran into a stumbling block, over and over again in reading and scoring these essays: just because students know the name for something doesn’t mean they understand the thing: and just because students remember the name for something doesn’t mean they remember how to spell it.

Let me note, here and now, that these students are brilliant and courageous for even trying to do this damn test, for even trying to write three college-level essays in two hours AFTER answering 45 difficult multiple-choice questions in one hour. Also, because this was written under pressure in a short time frame, and with almost certainly only one draft, mistakes are inevitable and should be entirely ignored when they don’t get in the way of understanding. I knew what every one of these students were trying to say, so I ignored their spelling, in terms of scoring the essay. I also ignored their generally atrocious handwriting, not least because mine is as bad as any of theirs and usually worse.

I just thought this was a fine example of knowing a term but not really knowing it. Ya know?

(Also I apologize for the image quality. Just trying to make a point. And the picture is not the point.)

The first one gets it right. Another one gets it right — but spells “English” as “Enligh.” Also please note the spelling of “repetition” which students repeatedly struggled with.

Fun, huh? I scored 695 essays this year. Last year it was over a thousand. And that exam passage also used anecdotes.

I’m really not trying to mock the students; just using this fact to show that knowing a term doesn’t mean you understand the term, because the word is not the thing itself. By the same token, knowing the spelling doesn’t mean you know the term, or that you understand the thing itself; which is why we ignore misspellings in scoring these essays. I think understanding the thing is much more important than knowing the word — and I’m a word guy. I love words. (Flibbertigibbet! Stooge! Cyclops! Wheeeee!) But I’m a word guy because I think this world is magnificent and incredible, and I want to understand as much of it as possible; words help me to do that, and to share my understanding of the world we live in. That complicated image I used above to show how some people can’t explain things well? Here, I’ll bring it down here so you don’t have to be confused which one I’m talking about.

This makes a few important points, even if it makes them badly. I do like how it goes from an image of the Earth, to a jumbled collage of colors inside the head, to the one word “world.” I think that, once you can follow it, makes this point well, how much translation and simplification happens between observed reality and the words we use to represent them. Though it should also lead to another head, of a listener, and show how that one word activates their own jumbled collage of colors in their head represented by the word “world.” (Far be it from me to suggest making this more complicated, though.) Because communication happens between two minds, and both minds contribute to the communication: which is why language works despite this simplifying process.

I do also like the statement at the bottom of the image: “Change the map, you change the world.” (Even though I hate how they capitalized and punctuated it.) Because that’s the last point here: while words are not the things they represent, they are incredibly important to our understanding of the world and our reality. Because we think and communicate in words. Not exclusively: my wife, for one, is deeply eloquent in communicating with images; my dogs can communicate with a look; musicians communicate with sounds that are not words. And so on. But language is our best and most effective form of interpersonal communication: and also one of the main ways we catalogue and recall our knowledge inside our heads. So getting the names of things right is incredibly important to our ability to use the information we know, and to communicate it to others. And what is the most important factor in getting the names of things right? Understanding the things we are talking about.

Because a rose by any other name would smell as sweet — but if you want people to know you are talking about one of these, you better call it a rose.

And for my sake, please spell it right.