Yesterday was a bad day.

That’s why I didn’t get a post up; I had one, about half done, which I started last Thursday; but yesterday I couldn’t handle finishing it and posting it.

Because yesterday, I lost faith in myself.

It’s pretty easy to do, really; I’m human, I make mistakes. All the time. Sometimes those mistakes are easy to brush off — I’m terrible at estimating time and distance; I know this about myself, so usually I don’t trust my first instinct when I think, “Oh, that’ll only take ten minutes to drive there. What is it, five miles away?” Because I know both of those numbers are wildly inaccurate. So if I need to know the distance, I will look it up; if the time to get there is important, I will double my original estimate. Or triple it, maybe. So that means I generally leave early and arrive early: but that’s no problem, because I get up every day at the crack of dawn anyway, and if I arrive early, it just means I don’t have to search for parking or an empty seat, which I hate doing anyway.

What I don’t do, however, is get mad at myself for mistaking the time or distance, and decide that I’m an idiot who can’t do anything right, and I’m therefore doomed to a life of mediocrity and failure, and it’s my fault for not working hard enough, or learning enough, or making the right decisions in the past. No, I save that kind of existential crisis for when I’ve done the worst thing I do: screw things up for somebody else.

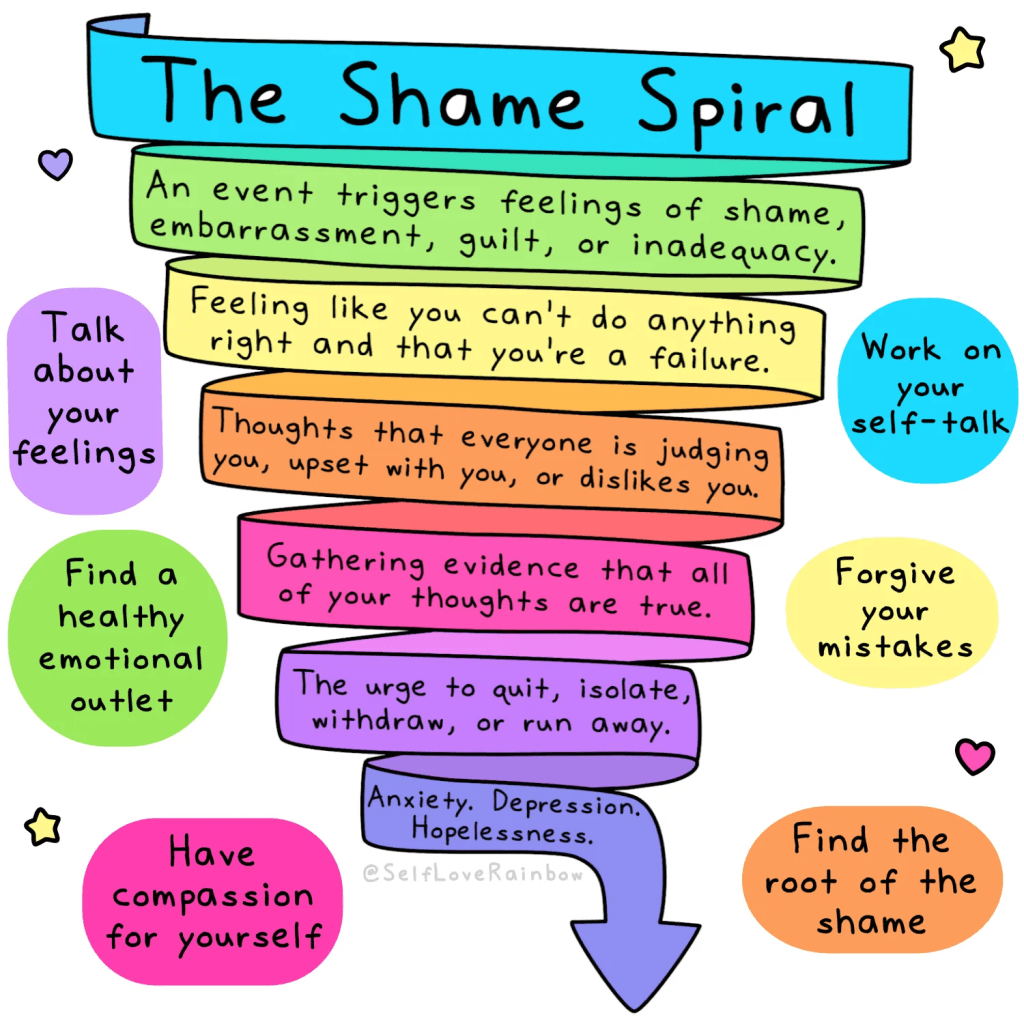

It doesn’t have to be a big thing. If I give bad advice, or advice that doesn’t help; if I teach badly, or fail to control my class, and get called out on it; if I try to do a thing and fail at it: any of those are enough to send me into a certain kind of shame-spiral, when I start thinking, Well, if I can’t do that right, then I probably can’t do those other things right; and that means everything I do is wrong, and I’m useless and stupid and I’ve wasted my life and harmed people by inflicting my stupidity on them when what they really need is someone who can help them. Basically, I think of myself as an intelligent person, and if I experience something that makes me feel unintelligent, then I doubt everything connected to my intelligence, and everything that I’ve ever done comes crashing down like a house of cards.

Of course, this is not a new phenomenon. And it is not unique to me. There’s a whole thing.

The bubbles around the edges are the ways to fight the downward spiral. I didn’t do those yesterday; I went straight to avoidance, and spent most of the day playing Minecraft. (I’m going to have to do a post on Minecraft, by the way, which I have only discovered this last year — that is, I knew about it, but I didn’t know that I would love it as much as I have grown to in the last year.) And so last night, I couldn’t sleep: because I was ashamed of having done nothing useful yesterday, including this blog, which I really do want to keep up with; and I failed. I blew it. I must be a terrible person…

Fortunately, my shame spiral this morning was interrupted by two things: first, I started writing this blog while I was eating my breakfast bagel, with the intent of finishing it tonight, because I can certainly accept posting one day late (Have I mentioned that I’m not real big on deadlines?), and so that reminded me that I can give myself one day of grace on my tasks without assuming that I am worthless; and second, I had to stop writing this blog so I could go to school. And while I was completely exhausted at school today — I was falling asleep while I was grading AP essays this morning (That is not a comment on how boring those essays were [Yes it is.] and also I surely did not lose focus on the essays while I was determining their final score […]) — and that made me cranky as hell, I also taught today. And I taught well. We went over the climactic end of the first act of The Crucible, and while my other class is not grasping the play, this class is. My AP Lit class is really getting into the details of Donald Barthelme’s amazing story GAME (Though they still haven’t figured out why Shotwell has the jacks). The Fantasy/Sci-fi class finished another chapter of The Hobbit, and I got to do a Mirkwood-spider voice, which was fun.

And now here I am, back trying once more to finish this blog.

So I am not stupid. I am not lazy. I am not incompetent, or incapable.

It is true that I’m not sure I have the level of expertise that makes this blog worth reading. Depending on the subject: when it is literature or teaching or writing, I’m fine; I understand those things better than most people, and anyone who understands them more than I do is always welcome to take issue with what I say. (Anyone is, really. Please feel free to comment on the post, or use the Feedback link on the bottom left of the screen, or go to the Contact link at the top. I’d love to hear from you, for whatever reason.) But the post I started last week is not about any of those things, so I’m more uncomfortable about it; hence, yesterday, when I was doubting myself and my abilities and my worth, I couldn’t gather the confidence to say what I want to say on the topic.

But, see, I don’t really write this blog as an expert. As I said, in literature and teaching and writing, I think I can at least hold my own, at my level — you will not find any doctoral theses on this page — but otherwise, when I write about politics or society or life, I’m not writing as an expert. I’m writing as a person. I have my perspective. I think the value I offer in this blog is not necessarily the brilliance of my insights: it is the clarity and the precision, and to some extent the humor, that I add in the writing of my insights. Basically, I’m just a guy with some ability to observe the world around me, and crystallize what I observe into a thought: and a genuine ability to put all that into words. And if that’s enough to make you read what I write, great: I hope my words on my perspective help you to have some thoughts of your own. I don’t think of it as advice.

If it hasn’t become clear, the specific problem yesterday was that I gave a student advice, and it wasn’t good advice. I mean, so it goes, right? I gave it my best shot, I didn’t make the best call. Nobody died, nothing was permanently broken. But I got into this thought pattern like: If I don’t give good advice, what am I doing teaching? If I don’t understand teenagers well enough to know what they should do in a certain situation, why do I work with them? Why should they listen to me? And if I’ve wasted 23 years of my life teaching when I shouldn’t be doing it in the first place, am I doing that only because I need to avoid being a writer for real? And I’m just fooling myself into thinking I’m a good teacher when actually I’m just kinda charming and easygoing, and so the students like me because I don’t make them work too hard, and that’s why I’ve kept my job even though I’m basically incompetent and, let’s face it, just pretty fucking stupid, right???

And what the hell am I doing offering my wisdom on this blog if I can’t even give good advice? Why would anyone listen to me?

I dunno. Why would anyone listen to anyone? Because sometimes, we get things right. Even if sometimes we don’t.

So here’s what I want to do. I don’t want to give advice: because I don’t know more than other people do, except in my small areas of expertise. But I do want to share some of the things I have figured out. I want to share my understanding, my perspective. And if it is helpful, or if it is interesting, then great: and if not, come back next week and see if I have anything better to say.

Okay?

Here we go.

#1: Love really does make the world go round.

My greatest joy is my wife. Living with her, seeing her, talking to her; supporting her, cheering her on, protecting her, watching her be amazing. She is my everything: because I love her. That keeps me wanting to do more with her and for her, and keeps me from being tired of her or resenting her or any of that other shit that comes between people. I am incredibly lucky that I can still feel this strongly for her after almost 30 years: but if I didn’t, if she didn’t still love me, then I would hope we could amicably separate, and go find other people to love. Because love is the most important thing in our relationship, as it is the most important thing in any of our lives. That love is more important than the relationship: the relationship remains because the love remains (And if we fell out of love, we might have a companionable love that would remain, and we could stay in that kind of relationship, and that would be fine: as long as there is love. It doesn’t always have to be the same kind of love. [Though I hope it does stay. It’s awfully nice.]), and the love is what matters, more than the relationship.

I write because I love it. I read because I love it. I teach because, basically, I love humanity. I am a pacifist for the same reason (Even though sometimes I want to hit my — well, maybe not my students. But I want to hit things around them, you know?). Every important thing about me is based on what I love, or what I don’t.

Love is everything.

#2: Life is long — but never long enough to do everything you want.

I hear people talk about how fast time goes: and I don’t understand it. I mean, sure, my childhood is loooooong gone, and I don’t remember everything that happened between then and now; so that might seem like it was a shorter time than it should have seemed like; and I have definitely felt some dilation of time in the last few years: I cannot fathom that the pandemic and the quarantine were three years ago. So I definitely do that thing where I go “What?!? Three years??? Seriously? Where did the time go?”

But then I actually think about it: and the last three years have been — three years long. I’ve done a whooooole lot of stuff in that time. A lot of it is the same stuff over and over again, but it’s been different every time. And it’s always like that. Life is very long. I hear the cliches about how we only have a very short time on this Earth and in this life, and that’s true: but only from the perspective of mountains. From a human perspective, we have a very long time to live. My students are so goddamn young; and I am 30 years older than they are. And 30 years? That’s a long fucking time. If I have 30 years left to live, that’s a long fucking time left. A very long time.

At the same time: in those 30 or 40 or 20 or however many years I have remaining, there are more things that I will not do, than there are things I will do. Partly because I will have to spend a huge amount of those remaining years doing shit like — grading AP essays while I try not to fall asleep. And that time lost will be sad, because it won’t be spent doing things I love. And it should be. Because see #1.

So we have to pick and choose what we spend our time doing. It’s important to choose, and to do it intentionally, and thoughtfully, as much as we can. Don’t let time slip by without paying attention to it at all; because we have a lot of time — but we can still waste it, and we shouldn’t. We should love our lives, as much as we can. Because #1.

#3: There are three things you can have with any job, any task, anything you buy or hire for: you can have good, you can have fast, and you can have cheap. You can only have two of them at a time. So if it’s good and fast, it ain’t cheap; if it’s good and cheap, it ain’t fast; and if it’s fast and cheap, it ain’t good.

This is the best single piece of wisdom I ever got from my dad (Though there are a lot of other things he’s taught me, more than I could count. It’s just that this is the best.). I think about this all the time. I’ve written about it a lot of times, too. Hiring a plumber: not cheap. But usually they do good work, if they’re professionals; and it’s always MUCH faster than doing the repair yourself. Or you can think about it in terms of buying a car: you can get a POS rusted-out Mustang, that still might be fast, and it will be comparatively cheap: but that won’t be a good car. Or you can get a good, cheap car like a used Toyota — and it will not be fast. Or you can buy a good fast car: but it’ll cost you. Or getting music on the Internet: you can get free music without ads (That’s what I’m calling “fast” in this case: no download delays and minimal interruptions), if you don’t mind listening to shit on Soundcloud; or you can get good music fast (without ads) if you don’t mind paying for premium services; or you can get free good music on YouTube (I’m currently listening to this, which I find both beautiful and amazing, but I also genuinely feel bad for this guy’s forearms. It’s like you can smell the tendonitis in the air, like smoke.) if you don’t mind sitting through ads.

Also: you don’t always get two. You can get only one. Or you can get none: because you can buy expensive shit that takes a long time to get finished, and when it’s done, it still sucks.

#4: The most important thing in any relationship, from friendship to love to family to business to neighborhood association to — anything — is communication.

I’m teaching argument right now, and if my students are understanding it, they should be figuring out that the first key to any argument, to understanding what someone else is saying, is always to define your terms. And clarify your meaning. And show where you get your information from, and why it leads you to the conclusions it does. And the same is true in any interaction: I am a good teacher because I want to understand my students, and I’m good at making them understand me. My wife and I still have a strong relationship, apart from our love, which is irrational and magical and incomprehensible and the most powerful force in the universe, because we communicate: because we tell each other what we think and feel, and we listen when the other is talking. I get along with my coworkers because I talk to them and listen to them. My students don’t complain about my grades because I am clear about why I give students what I give them — and if they have opinions about those grades, I listen to them, fairly. And if their communication makes sense to me, I am willing to change the grade. Their parents don’t complain about me because whenever they have a question for me, I answer it, fully, completely, and honestly.

Corollary to #4: communication requires honesty, which is why honesty — not patience, not courage, not intelligence nor openmindedness nor anything else — is the most important virtue.

No, you don’t have to be honest all the time. Yes, you can lie and say someone looks good in that outfit, or the food was tasty when it was not. But understand the consequences of those lies. And be as honest as you can.

#5: Everybody should have pets.

I have no opinion for or against children: if you want them, I wish you the very best; if you don’t, I wish you the same. But everyone should get pets. They are pure love and they teach pure love.

I always use the dogs for this, so here’s a video of Dunkie the cockatiel whistling. He’s adorable, too.

#6: Everybody should exercise, even if it’s only walking. Or dancing.

When I was a kid, I rode my bike everywhere. So much better than driving. Now I walk my dogs every chance I get, and also go to the gym. Movement helps with everything physical, mental, and emotional. We were made to move: so do it. Make sure it is something you enjoy, or you won’t do it — but when you enjoy it, do it as much as you can. It’s always good for you.

#7: Doing it yourself is better than buying it: but see #2. And #3, because doing something yourself instead of buying it is cheap, which means you can’t have it be both good and fast.

I was thinking of this in context of making food. Cooking yourself is healthier, in this country; generally cheaper than food from a restaurant (If it’s not cheaper, it’s DEFINITELY healthier), and if you can do it right, it tastes better, too. My advice for cooking is to learn a couple of specific dishes, and really master those: I can’t make eggs, but I can make three different kinds of mac and cheese, and they are all AMAZING. Also I am good with sandwiches. And my wife says I make good salads, too.

But it goes beyond that: my wife and I (with my dad’s help when he came for a visit) painted our first house, the entire exterior, two coats; and we did a hell of a job, and it was an accomplishment I was proud of. It was worth doing. But it did take a damn long time, I will say. It was a lot of work. Because of that, it is certainly worth it to hire an expert to do things for you sometimes, rather than take the time to do it yourself, always, because #2 means you have to pick and choose where and how you spend your time.

But if it’s important to you, and if you love it, do it yourself, as much as possible. Learn how and then do it.

#8: Everybody should read.

More than we do, unless you already read as much as you possibly can. I’m not against watching TV and movies and playing video games, and all outside/physical activities are good too, as is just relaxing and doing nothing. But we all need to read. It does more for the mind than any other intellectual activity. It brings us closer to the world every time we do it, because good writing is about the world. And writing is communication, which allows us to build and strengthen relationships, every time we read. It’s just the best thing. We should do it more.

Also, it will prevent the arrival of the world of Fahrenheit 451, which is closer now than ever before, and getting closer all the time — and that is not a good thing.

Also: everything is better with music. So listen to lots of music.

Now I’m listening to this. And to be honest, I have something of a pseudo-crush on the singer/songwriter/rhythm guitarist for this band. Which I’m only saying because honesty is important. And nobody is 100% straight. And damn, he’s got a good voice.

Also, this is maybe my favorite love song. Though I don’t have a crush on this singer. But he does have an amazing voice. Damn fine piano player, too. And I have no idea how he made this gruesome concept into a romantic song — but he did.

And this is one of my favorite songs about life. Which I should listen to more. It makes me feel better about myself.

#9: Put your own mask on first.

When the oxygen masks fall from the ceiling in an airplane emergency, what do they tell us to do? Put your own mask on before helping anyone else. Because if you pass out from lack of oxygen, you can’t help anyone.

I suck at this. I sacrifice myself for others all the time. Not in the grand sense: there’s almost no one I would be willing to die for; and the ones I would be willing to die for, I don’t want to die for, because I want to stay alive so I can love them and be loved by them. But I give up way, way, WAY too much of my time and energy for other people. I fight for my political beliefs because I want to do good in the world. I spend too much time working on my teaching because I want to help my students. And I do these things even when I can’t find the strength to do it: because it’s important to me. And then, when I do take a day off to play some Minecraft, I feel guilty about it for days afterwards. I get mad at my wife when she does things that I was going to do — say, vacuum or wash the dishes — because I was going to do them, and she shouldn’t have to do my tasks. But one of my favorite things to do for her is to take a chore that she was planning on doing, and do it for her, so she can relax.

But the more I spend of myself on others, the less there is of me. We get used up. And we don’t realize it, because we think we’re happy helping others — and we are (At least I am [and maybe I should have included the statement Don’t Be a Selfish Asshole, but I feel like we all know that already. Right?]), but helping others takes energy. It takes time. It takes: when we give, we lose something, even if we get a little bit back from sharing joy and human kindness. Whereas if we would take the time to take care of ourselves, we would have more to spend helping the people we want to help, the more capable we would be to do the things we want to do, which would then give us more time and energy and satisfaction/happiness to be able to share more with others. Think of it in terms of #2: a low-stress life will let me live longer; and the happier and more content I am, the more energy and will I would have to do things that I want to do — like paint my own house. Or help my students learn how to write better arguments. Or learn how to cook eggs. But if I am stressed, then I don’t want to learn to cook eggs: I just want to order a pizza and watch TV.

So: take care of yourself first. And then take care of other people. Definitely do the second one: putting time and energy into other people helps with #1, and makes all of our lives better; but do it second. Put yourself first. When you don’t need any more attention, you’ll turn to others; and it won’t be a struggle. Happy people are helpful people. Helpful people are happy people.

And that explains the current state of the GOP.

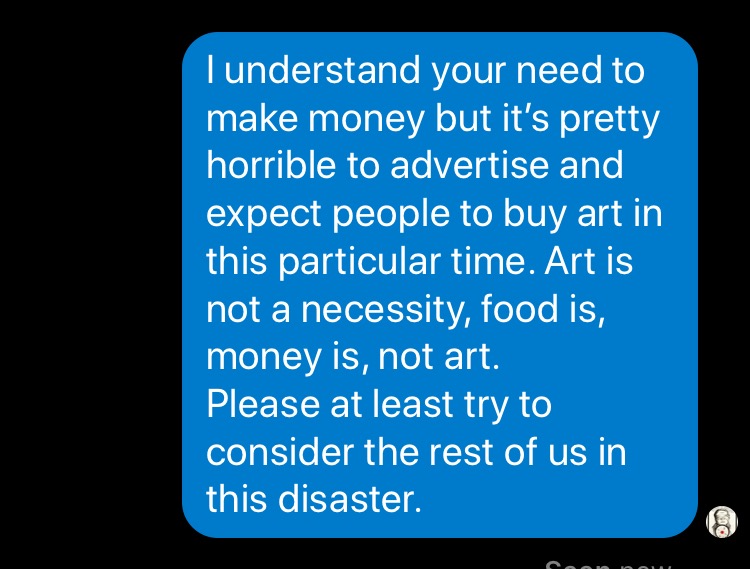

#10: Be kind. Everybody deserves it — though not everyone deserves it twice.

Make sure you are kind to yourself, too, and that certainly means removing unkind people from your life: and don’t feel bad about it when you do it. But otherwise: start every interaction with kindness, and try to end every interaction the same way. Why? Because