I had a nightmare the other night.

We all had one two weeks ago. But that one is just beginning.

I don’t have very many nightmares. Although, I don’t remember my dreams very often, so it’s possible that I am running through a constant string of terrifying dreams all night and then blanking my mind of them when I wake; I do suffer from insomnia, and so I frequently wake up in the middle of the night and think anxious and frustrated thoughts for a while before I manage to get back to sleep — if I do get back to sleep. That might be from that hypothetical string of nightmares suddenly reaching some kind of tipping point, driving me out of sleep and into waking anxiety.

Hmmm… a series of nightmares that build up to a climax of anxiety which ruins sleep. That does sound like the current situation of this country, doesn’t it?

In my nightmare the other night, my wife and I were going through a zombie apocalypse scenario. I don’t remember the whole thing, but at the end, we were hurrying through the halls of a Generic School-In-A-Dream™, and it was right at the point of the zombie plague where you look around, and you realize that the people around you are not people, but are rather zombies: and not only that, but the people are giving you that sullen, angry stare that zombies tend to have right before they charge. In my dream it was particularly creepy because the one I saw and recognized as a zombie was a child, and the signal that the kid was zombied up was a bloody rip across his cheek. In the dream, Toni and I ran; but we didn’t get very far.

I am scared of zombies. Of course I am, and not just because the idea of being eaten alive is utterly horrifying; I am also scared of the zombie apocalypse because I know how it would go: I would die. Quickly. I have no survival skills, I have no combat ability, I have nothing that I could even offer to a group of survivors that would make them want to take me in, other than how well I could correct their grammar and help them interpret poems: two skills that I expect will not be highly prized in the apocalypse.

As they are not prized now.

But that is much less frightening to me than this: what would happen to my family?

My wife is a badass; she can fight, she can shoot a gun (which I never have), she is tough as nails. She could make it, at least for a while — as long as I was not slowing her down. But she wouldn’t leave me, so I would definitely be slowing her down; and that means I would have to worry about her survival, because I would be a liability for it — I would be putting her at risk. And then, even if we decided we would run for the hills or something, we also have pets: two dogs, a great big tortoise, and a tiny bird in a cage. Okay, the tortoise I could release into the wild; he would probably be fine — would zombies even eat tortoises? (Note to self: story idea — zombie turtle. Talk about slow zombies.) — but my dogs and my bird would not be fine. And I wouldn’t leave them. And that, of course, makes me think about the horror of watching my loved ones get hurt. Which is, far and away and always, the worst nightmare imaginable.

And that — watching people we love get hurt — is also the current situation of this country.

So look: I said in my last post that, if you were looking to solve certain problems and thought voting for Donald Trump and the Republicans was the way to solve those problems, that doesn’t by itself make you my enemy. I don’t agree with you, but if you did it without meaning harm, I don’t have to consider you that way, with full and vituperative enmity. But the thing is, voting for Trump was unquestionably voting for someone who will do harm: and while that doesn’t mean you wanted harm to be done, it sure as hell means you accepted the fact that harm will be done. Maybe you lied to yourself, and convinced yourself Trump would not do harm; but that was a lie, and you probably know it. The man not only did harm to people in his first term, he promised extensive harm for this term, and he has been accused and found liable for causing quite a bit of harm entirely separate from the trials he was able to maneuver out of because too many people voted for Trump over the rule of law. Again, I assume that if you voted for Trump, you weren’t actually thinking, “I don’t want the rule of law any more!” Maybe you even thought that Trump and the Republicans are the law and order party; which is fine, in some ways they are — but Trump himself is not, and you should have been cognizant of that.

More likely was that you expected harm would be done, but you expected it will not be done to you or your family, and you were willing to accept that outcome. If you weren’t willing to accept that outcome, obviously, you didn’t vote for Trump. If you voted for Harris, thank you, and I’m sorry; if you didn’t vote, well. You’re not my enemy. But you’re pretty damn pathetic. And if you voted for harm that won’t fall on you, then I want you to think about that, for the next four years, and then hopefully for the rest of your life.

(And don’t try to both-sides me: I recognize that voting for Harris was voting for harm to continue in Gaza with American support. I would have been thinking about that for the rest of my life. I probably already will be, as I voted for Joe Biden, who has been supporting that genocide for a full year now.)

So, when I had this nightmare about the zombies rising up to kill my wife and I, I woke up scared. I realized immediately that it was a nightmare and it wasn’t real (Unlike the current situation in this country, which feels just like a nightmare but unfortunately is quite real), but like an idiot, I thought this thought: What if the situation were real? How would I actually deal with a zombie apocalypse? And while most of the time (I don’t think about zombie apocalypse survival strategies all the time, but I have thought of them, when it isn’t 3:00 am on a school night) I can fool myself (See? I do it too.) into thinking that I would escape by hiding or running or just being super clever, on this particular night, lying in the darkness, I faced the truth: I’d be screwed. I would die. Probably in an awful way. And I would have to either hope to die first (which would break my most important promise to my wife), or I would have to watch my loved ones killed in awful ways in front of me, while I couldn’t do anything about it.

And that feels just like the situation in this country today.

I know that there are people who would read this and think, “Psssh. You’re just being dramatic. Come on, comparing the second Trump term to a zombie apocalypse? That’s ridiculous! He’s just gonna lower taxes and deport some people. Maybe ban trans people. Maybe go after abortion and birth control. No big deal! He’s not gonna end the world!” To be fair, maybe people who would think that way wouldn’t read this, but my point is that there are people, probably the majority of the 76 million people who voted for Trump, who would think I was exaggerating with this analogy.

You know those people in zombie movies who act like complete idiots? Who refuse to accept the truth? They deny that the zombies are rising, or that they are eating people; they refuse to accept the obvious danger, or to accept that their own actions — making too much noise, for instance, or opening doors without knowing what is on the other side — are unacceptably risky? You know how those people almost always get other people killed before themselves succumbing to the ravenous horde?

Right. This country has at least 76 million of those people.

No, I don’t know if that is true. Not all the people who voted for Trump are fools who think he won’t do any harm. Many of them want him to do harm. They are gleefully rubbing their hands together in eager anticipation of all that harm he will do; they probably have a list of intended victims they are especially eager to enjoy the suffering of. Maybe they have a pool, and are laying odds on who will get it, and who will be first. (To be clear, these people are my enemies.)

You know those characters in zombie movies who are rooting for the zombies, and hoping all of humanity dies in hideous agony?

Right: you don’t. Because there aren’t any people like that in zombie movies. There are no people, in a story of struggle between humanity itself and the vile corruption that is bent on destroying humanity, who want humanity to lose. (Note to self: zombie movie in which some people actually want the zombies to win and talk about how much cheaper eggs will be when most of the population has been eaten. Maybe include the zombie turtles in this?) Which just tells you that some proportion of Trump’s voters are even worse than the people in zombie apocalypse movies.

Which is pretty damn terrible to think about.

I really don’t understand it. I understand (though I condemn) the partisanship that kept people from being able to vote for Harris or any Democrat; I understand (though I deplore) the willful ignorance that allowed people to “forget” that Trump will do harm, or the barely concealed hatred and aversion that allowed people to accept the limited harm they think Trump will do, which they think won’t affect them directly. I understand and agree with the anger that I know many people felt over the DNC’s choice of Kamala Harris, who is not and never was the best candidate the left could have produced for President; though also, I have to say this: people are nervous about what Trump will do now that he doesn’t have the same guardrails keeping him in line as he had the first time, and the truth is that the biggest guardrail Trump had to get over was — us. We are the guardrail. We are the defenders of democracy and freedom in this country, because the actual political power in this country resides in our votes. And we had one job: to vote against Trump’s return to the White House. As people trying to get our apathetic, lethargic, cynical, disjointed, selfish political class to produce an actually good candidate who could provide actual positive outcomes, we had several things we could have and should have done; but as defenders of democracy, we had one job: don’t let the would-be tyrant get back into power.

And we failed. We let the zombie virus out of the lab. For the second time, too, because this is the sequel: and as with every sequel, the stupidity of those who fail to take the zombie apocalypse seriously has to be even more appalling and egregious — because Jesus Christ, we already went through this once, weren’t you paying attention when all those zombies were eating people?!? — and the violence and gore the zombies inflict on people has to be even more shocking, even more horrendous, either more disgusting or on a much wider scale; because the sequel has to up the ante from the first installment, or there’s no point to having a sequel. Right?

What kills me is the breadth and depth of Trump’s win. I can’t just blame those frickin Pennsylvanians: every swing state went to Trump. My state, Arizona, went to Trump. There are Trump supporters all around me, wishing harm but not talking to me about it. You know how the worst thing in a zombie movie is when the people are actually turning into zombies, and you don’t know who is going to turn next? Who has already been infected? Who is suddenly going to surprise you by revealing themselves as your enemy, as the person who wishes you harm, or even as the monster who is going to do you harm themselves, who is going to take a bite out of your shoulder on the way up to your jugular? Everyone looks the same, all looking normal, all talking about things the same way — and then suddenly someone’s eyes roll up in their heads, their skin turns chartreuse, and they groan and start nomming on their neighbors? Don’t you think that’s the worst part of zombie movies?

Okay, no, the worst is probably when people get dragged screaming into a horde that tears them apart and eats them alive.

I hope that there won’t be anything even metaphorically like that in this situation. It is just an analogy; I don’t think the world is going to go through even a human apocalypse, let alone something like a zombie apocalypse. I know we will survive this.

But also, Nazis marched in Ohio this past weekend. So I’m really not sure there won’t be a scene of savage and shocking violence where someone innocent is dragged screaming to their horrible bloody death.

So my dark-of-night thought about the zombie apocalypse was: I’d probably just give up. I’d run for a while — if we’re starting with my dream, I’d be with Toni — and then I’d end up giving in to despair, and I’d have to do one of those hideously sad scenes where two people say goodbye and then let themselves die together. And when I heard the election results, I thought sort of the same thing: maybe I should just give up. I mean, this is clearly what the people of this country want, more than I want to believe they want it. But they do. I don’t just think ignorant and evil people voted for Trump; I think there were rational people, good people, who made a bad decision, but who thought it was the right decision. I want to think that, given a chance to talk to them honestly and openly, I could convince those people that they made a bad decision: and then maybe they won’t make the same kind of mistake again — but also, I failed to convince them before this election. I failed to make any difference in this election. However hard I tried, it wasn’t good enough; I wasn’t good enough to solve the problem, to prevent this terrible outcome, to protect people from harm. I thought, Why would I try again when I failed the last time?

And that’s actually why I recognized this parallel between Trump’s election and the zombie apocalypse, and why I wanted to write about it.

Because what zombies represent is hopelessness.

The basic concept of the zombie trope is this: people, who are unique and special and valuable individuals, become zombies, a horde of identityless, soulless, lifeless husks, taken over and corrupted by some vile invader — a virus, an alien parasite, Disney. Having been corrupted, the former humans stalk other humans relentlessly, and turn those individual people into more indistinguishable members of the horde. It represents all of our fears of losing our selves, our identities, in the larger society, which grinds us up and devours us (along with the visceral horror of cannibalism, the idea of being devoured, reduced to mere sustenance and then destroyed and consumed by those who should shield and succour you). Zombies are seen as representing our fear of the future, particularly of technology, and the advancement and growth of our society into something that either doesn’t recognize our individual human value — or doesn’t care about it. Zombies don’t care that I am a teacher, or a husband, or a writer, or a man who loves animals; to them I’m just meat. And zombies are the meat grinder.

Zombies are the Machine. Zombies are the Man, in the abstract sense of an authority that doesn’t respect or value us, that sees us only as grist for the mill, or at best fuel for the engine.

But none of that is the horror of zombies. (That’s not true: much of the horror of zombies is in the eating, particularly in the eating alive, which is just appalling in and of itself.) The horror of zombies is in their relentlessness: the horde keeps coming after you, and nothing can make them stop. They do not get tired or bored or distracted (mostly), because they are lifeless and thoughtless and devoid of all desires other than hunger. They can not be killed, can not be scared off. You can sometimes destroy them, such as with the famed head shot, or with something like an explosion, a consuming fire, a bulldozer: some kind of overwhelming force, far more than would be needed to stop a human who was coming after you, which shows the sheer power to be found in giving up (or losing) humanity. But even if you fight the zombies, and win the battle, you can’t win the war, because you will run out of ammunition, you will use up all of your resources, and the zombies will keep coming: because we got the guns, but they got the numbers, to misquote the Doors. And of course, every one of ours we lose is one that they gain. You can outrun them — but eventually they will catch up with you, because you will get exhausted, simply because you are alive and therefore you need to rest. The dead — or rather, the undead — do not need to rest.

That’s the main horror of zombie apocalypse stories. There is no escape, and no way to stop what is coming for you. What is going to eat you, or turn you into another part of itself. And the result of that inevitability, (I have to link that clip. Also, the third movie is an interesting re-interpretation of the same fear, being consumed and turned into the corrupted enemy.) of course, is despair: a loss of hope, and the subsequent surrendering to apathy and lethargy and numbness, and then death and destruction.

Hm. Sounds like depression. Also sounds like the situation in this country right now.

So that’s what I felt, what I thought, when I heard that Trump had won the election. Fortunately, because I spend most of my time outside of politics, I didn’t feel that total despair, I didn’t lose all hope — because hey, the zombie hordes aren’t outside my door. They aren’t stalking me. I understand that some people don’t have that luxury, that solace, because the hordes are stalking them, and they are in real danger; but, without being selfish or trying to sound callous, I am glad that I can take solace in that I can still live. I can still teach — and while some of my students are a different kind of soulless zombie horde, many of them are vital and wonderful young people who learn from me. So there is hope there. I can still write, even though it is harder to find the time and energy to do it, these days. Because this is neither a movie nor my dream, I do not in fact need to sacrifice my wife, or hold her while we both die; actually, we are both quite healthy, which is nice to say. And the pets are safe and well. So no, it is not the apocalypse, not for me. I have hope, and hope means I can fight.

And it is not time to give up hope.

I mean that. While many of the guardrails that held Trump back from his worst impulses last time are gone now, and he will act like what he is, a cross between Veruca Salt (not the band) and a shit-throwing gibbon (Note to self: that would be a good punk band name.), there are still guardrails in place. We should be disturbed by the ones that are gone, and we should work to put them back in place, or even replace them with improved versions; but don’t think that Trump will be able to do all the worst things he or we could ever imagine. He won’t. The military will not betray this country, the Constitution, and their oaths, for Donald freaking Trump: and without the military, he can never have a coup or become dictator for life. He can get every single one of the Proud Boys, and the 3%ers, and the Neo-Nazis, and the Karens for Trump or whatever, and march them all on Washington: and a single armored division would wipe them out in minutes. So he cannot overthrow the government. And while the Supreme Court, themselves corrupted by something vile and awful and alien — namely a level of arrogance that we haven’t seen, I think, since literal nobles before the French Revolution — have given Trump the green light to do whatever official act he wants — they also reserved for themselves the right to decide what is an official act. And if you think they would ever give up that control over Trump, or any other President, well. You haven’t seen any movies with the nobility in them. Honestly, the people backing Trump don’t want him to overthrow the government and destroy this country; this country is where they keep their money. The Supreme Court serves that crowd, the billionaire class who want to retain the rule of law because that protects their billions — and, not coincidentally, the Court’s own power. So anything that looks like Trump trying to overthrow the Constitution and set himself up as a king will be thrown down by those who already consider themselves our overlords.

So no, Trump won’t destroy the country, or our democracy.

But he’ll hurt people. A lot of people. Starting with the immigrants he deports, the women he strips of rights, and the trans people he tries to exterminate by allowing bigots to say trans people shouldn’t exist. And all of the people who love them, and will have to watch those people get hurt.

So in the face of that, we shouldn’t feel helpless or hopeless, and we shouldn’t despair.

We should feel sober. And frightened, especially for those who are in Trump’s crosshairs, although that may not be us and our families; it is surely people we know and care about, and people we should protect, support and succour.

We should feel so. Fucking. Angry.

And we should then focus that anger, that fear, that seriousness, on the task at hand: to fight the horde. To stop them from breaking down all of the doors, tearing down all of the walls, and especially to stop them from devouring people, whether they are our people or not. Because now it’s down to this: you are human, and you are unwilling to sacrifice those who are threatened for your own sake, especially for your own convenience, or for something as trivial as the price of eggs — or you are not. If you are not, you are of the horde, and you are our enemy.

All of you humans, all of my kin and friends and allies: don’t stop. Don’t give up hope: this horde will be defeated. This will be one of those zombie apocalypses where the zombie plague is cured, or something happens to wipe all the monsters out. You know why?

Because Donald Trump is an unhealthy 78-year-old, who very carefully and determinedly built a cult of personality around himself. For reasons I can’t really fathom, he was incredibly successful at that — more successful than any demogogue since 1945, probably. He turned the United States of America on its head, and got us to choose the path that leads to our own destruction — twice — and to cheer while we did it. It’s goddamn 1984. (And by the way: I’ve read 1984. And I understood it. My allusion is accurate.) But the best and most secure guardrail that will help protect us from total collapse into the evil and anarchy of Trump’s world vision is that Donald Trump will not live forever — and while he is alive, he is old, and unhealthy, and lazy. Half the stuff he could do, he won’t do, because he’ll be too busy watching Fox News and telling his cronies that he really is smarter than everyone else. And because only he himself is the focus of that cult of personality, nobody else will be able to step into his shoes when he dies.

In the meantime, before he leaves office with his diaper and his hands full of his own feces, or before he drops dead of a massive coronary, he will do harm. To people we know. To people we love. To people. And so that is our fight. To stop that harm when we can, to mitigate it when we can, and to balance it always by being so fucking aggressively kind that even the zombies would decide not to eat us, would instead pick us a flower and smile with their broken teeth in their rotted mouths, and say, “Thaaaaangk yyyooouuuuuuuu!”

I’m going to shoot for that result with my classes, too. We’ll see if I can pull it off.

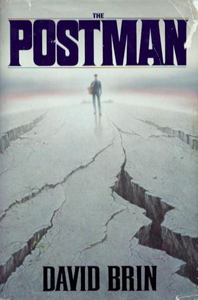

As for me? After I thought I would give up in the zombie apocalypse, and then told myself that I would never give up — and then thought that I am too weak, too ignorant, too pathetic and lame to actually be of any use to anyone in that dystopian scenario, I remembered something. I remembered a different post-apocalyptic book I read, years ago: one where the collapse is due to a disease that simply kills people, not one that reanimates the dead — you know, a much more realistic book. Science fiction, of course, as the most accurate and truthful books often are. And in that book, the main character is, at first, a conman, a liar who manages to get accepted into the broken anarchic society that replaces our modern one after the collapse; he gains food, shelter, allies — a life. And he does it first by lying. And then, he does it by storytelling, and entertainment: he puts on plays for the fortified groups he visits; he recites poetry. As years turn into decades, he helps to teach the children born into this terrible world, and because he travels from place to place, around and around a particular circuit, he becomes something of a messenger, helping these small, isolated communities to build connections, and to unite, in the end, against the common foe.

By the end of the book, it becomes clear that the conman, the entertainer, has actually done something genuinely valuable for the people he thought he was just lying to: he has given them hope. He has inspired them to keep going, even in the face of despair, even in the face of seemingly insurmountable odds. He has brought people together, and reminded them of what it means to be human, to be more than savages slaughtering each other for food and warmth. To be people, rather than part of the faceless horde.

The name of the book is The Postman, by David Brin, a wonderful SF writer. It was turned into a reeeaaalllllyy bad movie with Kevin Costner in the lead role; it was so bad it has probably been entirely forgotten. But the book was actually good.

And you know what? I can do that. I could do all of that. (Not the lying, hopefully, because I am not good at it and I very much hate doing it. But I can.) I can be entertaining, and I can bring people together, and I can maybe inspire people to keep going, even in the face of despair and the seemingly insurmountable numbers of the horde.

I can survive the zombie apocalypse.

We all can.

Let’s go.