I got stopped by a fellow teacher this past week and asked a question I had never thought about before: between the two most common science fiction future predictions, that is, that humanity will evolve and transcend in some way, or that humanity will destroy itself, which did I think was the most likely? And although I had never thought about that before, I have read enough sci-fi to have encountered both of these predictions — actually, in my new elective class on fantasy and science-fiction literature, we have read both a dystopian novel (Feed by M.T. Anderson — HIGHLY recommend) that predicts that humanity will destroy itself and the Earth’s ecosystem along with us; and a short story by Isaac Asimov called “The Last Question” (Asimov said this was his best story. It’s probably not — but it’s a cool idea, and it’s very well realized. Also recommend. But not as highly as Feed.) which depicts humanity evolving and transcending. Along with our computer intelligences, I might add; which is a nice element to include in this unusually hopeful story. So I was able to formulate an answer, quickly; one that responded to the question but also considered some of the complexities in the topic: I said, immediately, that the doom option is far more likely — but I also pointed out that said doom is certainly not going to be the actual end of the human race, because we are enormously adaptable and incredibly good at surviving, so some people would live through the end of the rest of us, and those people would end up being very different from the people who came before the doom; and therefore those people may be said to transcend. But also, I asked what was meant by “evolve” and by “transcend?” Humanity has largely stopped evolving physically, because we now evolve societally; our greater height and longevity, our now-selective fecundity but also our incredibly improved survival rate — all these are changes that have been wrought by society, and not by physical evolution through natural selection. So is evolution to be defined as something that happens naturally through the same process of environmental pressure which differentiated us from the other great apes? Then hell no, humans will not evolve. But is evolution simply about the changes wrought on the species by their — our — continued survival and our steady adaptation to differing circumstances? Then yes, we will continue to evolve. Also, does “transcend” mean changing who we are as a species? Being born different, as the kids say? Or is it about changing individuals after birth? That is, if I am born as a normal weak-ass human, but then I add machine elements to my body, and end by uploading my consciousness into a robot body: have I transcended? Have I evolved?

Anyway, the point is I talk too damn much. But also (And this is more the point): I’m very smart. I was able to start answering the question, and then think about both the question and my answer, while making my initial point. I thought of these two works I have named, and thought about how they fit into the spectrum of future possibilities. I could have kept going. I could have turned this into a lesson, or even a unit, without thinking too hard. (We should also include “Harrison Bergeron” by Kurt Vonnegut. Great story about evolution, and also dystopian doom. And “By the Waters of Babylon” by Stephen Vincent Benet is a nice example of people surviving past the cataclysm, and maybe becoming better? Maybe stronger?) I could have put this to students, and maybe helped them to recognize the importance of trying to become better, rather than worse, even though worse is MUCH easier. I have used it as an example here, but I could have turned this into a whole essay; it might have been a good one.

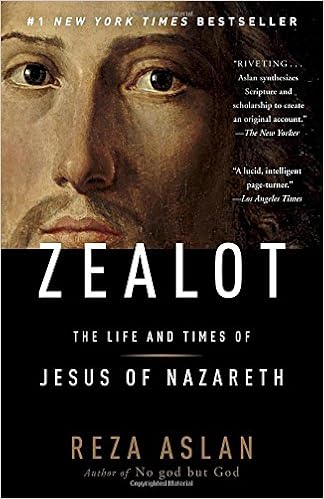

I am proud that I can do that. I am proud of my abilities. I read well and remember what I read; I think well and speak well and write well. Over the last 20+ years of teaching, I have actually learned to think like a teacher: surprising, considering that I didn’t even think like a student when I was growing up. Part of why I do that, why I think like a teacher? I’m proud of being a teacher. I’m proud of what I have done as a teacher. Not as proud as what I have done as a writer; I still think art is more important than education, because education has been co-opted and commodified, and also to some extent Balkanized (Meaning it has been broken up into small pieces, as the Balkan states were broken off of the Soviet Union; now there are lots of them, but they are individually much less than they used to be, partly because they are hostile to each other. Huh. I actually didn’t know that last part was in the definition. Now I have to think about whether that applies to teaching. Yeah, probably; I have often had conflict — beef, as the kids say [By the way: I do that “As the kids say” thing precisely because it is “cringe,” which is hilarious. I can actually make my students shiver with loathing when I say something like “No cap, for real for real.” I love it.] — with other teachers, and that probably is a result of the system, at least in part.); while that has definitely happened to art on the internet (which was where and how I discovered the term Balkanization, in a description of how the internet has affected art), art is able to — well, to transcend that process, and remain valuable, which education has struggled to do. So when asked what I have accomplished that I am proud of, the immediate answer is always: my books. I have written books. They are good books. I am proud of them. Only after I have said all of that — and probably much more — do I maybe add — “Oh, and I’m proud of teaching, I guess.”

And that’s why I’m writing this: because two weeks ago I wrote about value and worth and price, and I recommended that people stop buying stuff, which theme I wanted to expand on lest I be too holier-than-thou; and both that piece and this one are in response to the number of my friends who question their value and their worth: particularly in terms of their art and their accomplishments as artists. I do it too, and for some of the same reasons; but I do it less. Because I’m a proud man.

And Pride goeth before a fall.

Okay: so what is pride? What does it mean to be proud of something, or of someone? What does it mean to be proud of yourself — and is that the same as being proud as a person? Of having pride? Is pride good, or bad?

According to Christian values, pride is bad. We should instead be humble. But okay, what does that mean? My immediate thought is that humble means “Not proud;” so I should define “pride” first, and then “humility” in relation to it. I suspect we are more familiar with and have a better understanding of pride, especially we Americans. So we’ll start there.

I think of pride in two contexts: pride in one’s accomplishments, and the pride a parent feels about their child. That’s not to limit it to those: I am proud of my wife, I am proud of my brother, I am proud of my father (Maybe even more so than he is proud of me…), I am proud of my friends. I am proud (in a way) of things about me that I wouldn’t label as accomplishments, like my intelligence and my empathy. But the first things that come to mind are the first two I stated. When I talk about being proud of my accomplishments, I think that feeling is a sense that what I have done is good, is important, and is something I think is defining for me. I’ve done stuff that I’m not proud of (Which should be a simple statement describing things like “I drove to the post office today” but has a strong negative connotation, implying things that I have done which I am not only not proud of, but that I am ashamed of; those things also exist), and some of it is good and important — like food. I make dinner sometimes. I made dinner last night. Sandwiches. Pesto, tomatoes, mozzarella cheese. Potato chips on the side. (I didn’t make those.) Delicious. Food is good and important, the fact that I make the food sometimes so my wife doesn’t have to is good and important — but I’m not proud of that. Because I don’t see it as defining.

That’s another aspect of this we struggle with, I would guess. It’s hard for us to define ourselves. It’s particularly hard for artists to define ourselves, because most of us — almost all of us — have other jobs. Almost no one makes their living exclusively from their art. And here in our capitalist society, we define ourselves first and foremost by our jobs; that is, by our income-earning vocations. Even that word is misused: it means a career or occupation (One regarded as particularly worthy and requiring great dedication, the Google tells me, so the definition is closer to what I want it to be, and I’ve just been misusing it. But I wonder how many people who use the word use it to that full definition.), but it comes from the Latin word for “to call,” vocare, so it is a calling. Something we are summoned to, something we are compelled to do — no, even that doesn’t have the right feel, because honestly, I am summoned and compelled to earn a paycheck because I have a mortgage and because I need to buy tomatoes and pesto and mozzarella for my sandwiches. A vocation should be something that thrums the iron string of our soul that Emerson wrote about in On Self-Reliance. Something that makes sense of us, and by which we make sense of ourselves and our world. My father spent five years or so working as human resources director for a tech company in Boston; but his vocation was always particle physics, and when he went back to that, he made sense to himself. So he is proud of his work at SLAC [Stanford Linear Accelerator Center], and not as proud of his work at the tech company. Similarly, I am proud of my writing, and proud of my teaching — and I mean, I guess it’s cool that I have put a lot of work into home renovation projects over the years.

So that’s the first part of pride. When you do something that is good and important and defining, then you are (or should be) proud of that. “Important” is a word in there that probably needs defining too, though it is definitely subjective for me: there’s no real reason to think that my writing is important, as I have not been groundbreaking or influential or even particularly successful with my writing; but I think it is important. And I see a distinction between my important writing, like this blog I keep trying to keep up, and my books; and my unimportant writing, like my journal or the emails I send, stuff like that.

So if that is pride, I’m not sure why it’s a thing that Christianity would be against. Other than, of course, the cynical assumption that the faith wants to put all goodness into God so that people need to rely on the church; if God is the source of all good things, then there isn’t anything for any human to be proud of, because we didn’t do that stuff, God did; he just let us borrow it. Personally I don’t like that. But then I’m not a Christian. That may be exactly the mindset they’re going for.

But I don’t think that’s the source of the idea that “Pride goeth before a fall.” (Hang on, let me check on that, because I used “Spare the rod and spoil the child” in an essay I wrote once for school and claimed it was from the Bible, and later on I looked it up and it does not in fact come from the Bible at all. I am actually proud of that essay in a particularly perverse way: I think it’s one of the worst things I’ve ever written, which it was meant to be, and it has been an effective example for my classes because it is so bad. Okay, so this one is from the Bible but I’m misquoting: it is “Pride goeth before destruction, and an haughty spirit before a fall.” Proverbs 16:18, King James Version) I think — though I agree that my understanding of Christian ideology is a pretty laughable foundation for a discussion — that the pride spoken of there is a different kind of pride: and now that I have actually found the correct quote, I feel pretty well confirmed in that.

It’s the haughty spirit. That’s the point. That’s the bad pride, the one that leads to karmic justice in some way.

See, there are plenty of people who take enormous pride in things that they didn’t even do. So it’s one thing to take pride in something that isn’t good; I’m pretty damn proud of my longstanding hobby (One might even call it a vocation?) of stapling papers in the wrong corners in order to mess with my students:

But there’s nothing good about that.

And then there are plenty of things I am proud of which are not important — like the video games I have beaten, that sort of thing. And I already spoke of things that aren’t defining, like cooking dinner for my family. Those things may not really deserve pride — and because of that it does make me question whether I feel proud about them — but regardless, there is no harm in being proud of things that don’t really matter much.

But then there are people who are proud of things they didn’t even do: like being American. Or male. Or tall. Or white. Don’t get me wrong, you can like those things, you can appreciate being those things (I’m not really sure why you would, but to each their own): but what on Earth would make someone proud of being born in this country? What did you do to make that happen? What time and effort did you put into it? Now, if you emigrated here, went through the enormous upheaval of moving to a whole new country; if you made a life and a home here, and created a place for yourself: that would be something to be proud of. But if you are proud of the fact that were born here, well. Bill Hicks has something to say about that: (**Please note: this clip is not safe for work.)

In To Kill a Mockingbird, Miss Maudie talks about Atticus’s shooting ability, once it is revealed that he was called One-Shot Finch, after he shoots the rabid dog. The kids can’t understand why Atticus never talked about how he was a dead shot, and why he never goes shooting if he is so good at it. Miss Maudie theorizes (Falsely, in a way, because he later says what he wanted his kids to think — that courage is not a man with a gun — but this point of Maudie’s also makes sense and might be part of his reasoning) that it is because Atticus recognizes that there’s no sense in taking pride in what she calls a God-given talent. She says that being born with a good eye and a steady hand is nothing that comes from hard work and dedication; it’s just a thing that is true about Atticus, like being tall.

I don’t entirely agree with Miss Maudie — I think that shooting a gun accurately would take a hell of a lot of practice, and therefore would be something to be proud of; but also, you would need to shoot in a good way, and also in an important way, for it to earn pride in my definition — but I see her point and I agree with the idea that taking pride in something you didn’t do, something you aren’t responsible for, is silly. That’s the idea of the Bible verse, too, I think.

See, if you put in the effort on something, if you really do the work, then it’s damn difficult to be proud of it. Because first of all, you’ve seen alllllll the mistakes you made in the process of learning; and if it is something hard to do, then you made a lot of mistakes. You also know, better than anyone, how much effort you have spent, and also you should know the difference that effort made: and that should pretty clearly show you that anyone else who put in the same effort would probably make the same progress — unless you were born with a gift of some kind that contributed to your ability, like having a sharp eye and a steady hand. But if it is something really difficult, then you also recognize that your sharp eye and your steady hand are not the things that make you good, or that make you great: they make it easier for you to be good or great — but only effort and dedication makes you good, or makes you great. The physical gifts are not something you did, so not something you should be proud of: the pride comes from what you put into making yourself into someone you can be proud of. Michael Jordan certainly has physical gifts that make him a great basketball player: but he’s Michael Jordan because he had the will and the drive, and he put in the effort. Therefore, I think he should be proud of what he accomplished. Shaquille O’Neal, on the other hand — well, he should be proud that he is apparently a very nice person. And then, of course, if you do what most of us do with our passions, and you look around at other people who do the same thing, what you are bound to find is people who do it better than you. Because nobody, not even Michael Jordan, is actually the greatest: there’s always somebody better. Knowing that keeps us humble, even if we have accomplished something to be proud of.

But even though it is difficult to take pride in what do, if that thing we do is a calling, if that thing is very difficult, if that thing takes years of dedication and effort to accomplish: then we have to take pride in it. We have to. Because there’s another aspect of pride.

The pride a parent takes in a child, that I take in my wife, my friends, my family, is not the pride of accomplishment. I mean, I’m proud that I support my wife in her art (and I’m proud I make her delicious sandwiches for dinner, without which she could not continue to make art), but otherwise? Her art isn’t my accomplishment. I did nothing to make her into the artist she is, not really. My support and sandwiches were helpful, but she could have done it without them, of course. But I am so incredibly proud of what she can do. So is that like the pride that dumb people take in being born between Canada and Mexico?

No: it’s something else.

The quality of an accomplishment that makes it pride-worthy, the aspects of it that make it (to one’s subjective viewpoint) good, and important, and defining, can be boiled down to one simple emotion: the most powerful emotion. Love. I write because I love what writing can do, and I love what writing is; and therefore I love writers — and therefore, when I write, I love myself. I love when I am able to create the effects that make me love writing. I am so very proud of those moments, of those effects, of what I did, and of myself for achieving them. And yes, it is entirely subjective: but then, often, so is pride. That doesn’t make it bad.

Pride is bad when it is not based on love. That’s the second half of the proverb, the “haughty spirit.” When one bases their pride on their contempt for others, then pride is bad. When one sets oneself above others, and is proud as a corollary to that, that is bad. That leads, in a righteous universe, to destruction: to a fall. (I know it doesn’t always. This is not a righteous universe.)

So really, it’s not that it’s dumb to be proud of being an American; it’s dumb to think that other people are lesser for not being Americans. (I knew that, actually. I am proud of my country. But also, I am humbled by it, because I can never do enough to make it the country that it should be, which means I am not fully worthy of it: so my pride does not create in me an haughty spirit. What a phrase that is. Don’t you just love the KJV?) It’s not that bad to be proud of being tall, or of being white; it’s bad to think that short people are worse off, or that people who aren’t white are somehow worse or less than white people. That’s where pride goeth before destruction: at least it is to be hoped that it does goeth before destruction. Because that kind of pride should be destroyed.

That’s not the pride that people have in their children, unless those people are really damn awful. Parents who put in a lot of work helping their kids to achieve something can take pride in their accomplishment, too, but mainly, parents are proud of their kids because they love their kids. And that love is pride; that pride is really just love.

I think that pride is love turned outwards. Love is generally directed into the person, or the pursuit, or the object, for whom/for which you feel the love; or it is turned into ourselves, as we enjoy the loved thing or the loved one being around us and bringing us joy. When we are proud of someone, as when we are proud of our accomplishments, we want to share that love with others: we want to express it, we want others to see it, we want everyone to know about it. That’s pride. I am proud of my books because I love my books. I am proud of my wife because I love my wife. I want to show off my books, I want to show off my wife, because I want other people to know of my love, and I want other people to understand how much I love, and why I love, and how lucky I am to have these loves in my life: both my accomplishments, and my incredible, incomparable wife.

Also: I am sometimes not proud of being an American. Because I do not always love my country. I am always proud of my wife.

But please remember this, whoever is reading this: if you work on something hard; if you think that thing is good; if you think it is important; if you think it defines a part of you: then be proud of it. Be proud of it like a parent is proud of their child. Notice that I have not spoken of the value or the worth or the price of the thing you do of which you are proud: love has no price, and so neither, therefore, should pride. You just feel it, and want to share it: and you should. Always. And if you are a parent: be proud of your child, especially when that child is proud of themselves. Love them for who they are and for what they do: and love yourself the same way. Don’t talk yourself out of it because you could have done better, or someone else could have done better, or it wasn’t exactly what you thought it would be: just love what you did, and love yourself for doing it. Be proud.

You deserve it.