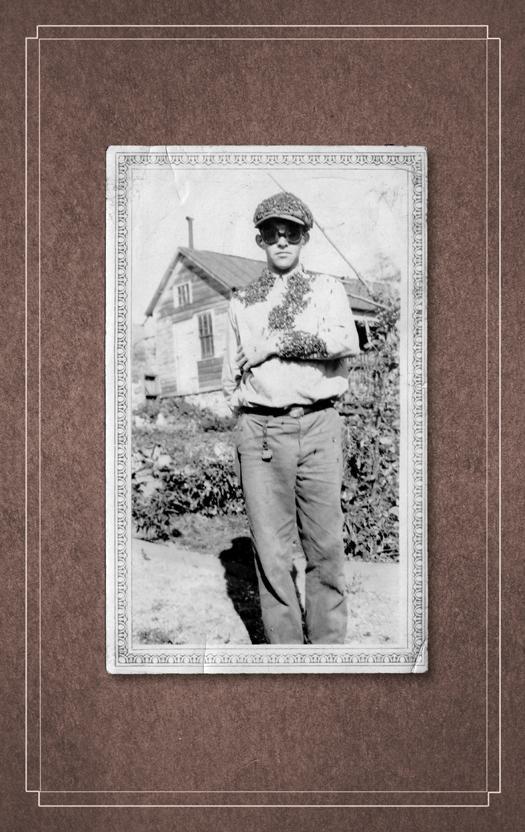

This is Hugh. Hugh rocks.

Miss Peregrine’s Home for Peculiar Children

Hollow City

Library of Souls

by Ransom Riggs

These three books make up one story, so I thought I’d just combine the review into one, now that I’ve read all three.

Before I say anything else, let me say this: I read all three books in a row, and didn’t get tired, or bored, or annoyed with the story or the characters or the writing. Since I generally have to space out my series reading with other books in between, this is a very good sign.

And indeed, these are very good books. It’s a type of fiction which I love: fantasy that is mixed into the modern world, like Harry Potter’s secret world of wizarding, like most urban fantasy and paranormal books, with hidden or open worlds of supernatural creatures. This particular series has sort of an X-Men flair: there are people hidden amongst us who are . . . peculiar. They have strange powers and abilities, some physical, some psychic, some essentially magical. They hide because they are often persecuted for their strangeness, and also because they are being hunted: by monsters.

The special twist in these books is that the author, whether prior to writing these or as part of writing them, dove into the world of found photographs. And believe me: it’s a good twist. I have rarely seen a better connection between images and text, other than in graphic and illustrated novels. The remarkable thing about these photographs is that they are found, some by the author himself, more by a group of collectors who shared their prizes with him.

The photos are all old, I assume at least a century or so; many of them have that solemn I-can’t-smile-because-this-image-takes-thirty-minutes-to-capture feel to them, though many others are instants that could not have been held for that long. Most of the images chosen for this book were doctored, but not by the author; the original photos were doctored, either in the composition or in the developing process. The doctoring generally isn’t terribly realistic, a truth the main character actually comments on when he first finds some of the photos, which then appear in the book and confirm what the narrator says; but it is, I have to say, enormously fun to think that the photos are real, and that rather than camera tricks, they are depicting people who are, quite simply, peculiar. As I said, it’s a good twist, and it improves the books, overall. There are some photos that were clearly chosen because they were interesting or they spoke to the author for some reason, and some of these have to be really pretty bent and folded and spindled to fit them into the narrative; there are others that are just thrown in for the sake of including the image, and so the characters pass by these scenes while traveling, or one of them mentions somebody they knew once, whose photo then appears. It does get a wee bit cheesy at times. But the photos are unfailingly interesting, and where they are used to give visuals that play a direct or important role in the story, they really add another dimension that most novels don’t have. It’s cool. (All three cover images are these found photographs, so you can see what I’m talking about. All three of those images are part of the story.)

(Warning: Spoilers Ahead)

Book I: Miss Peregrine’s Home for Peculiar Children

This one takes too long to get to the good stuff. But taken as the first part of a trilogy, it’s not bad at all — think of it like The Fellowship of the Ring, with a whole lot of traveling and getting to know something of the world the books are set in, and then it isn’t so bad. We are introduced to Jacob Portman, the hero and narrator of the series, and his family. The short version of his family is that his grandfather is awesome, and the rest of them kind of suck. Including Jacob, who is spoiled and self-pitying in the beginning.

But, it turns out, Jacob’s grandfather was connected to the world of the peculiar, and when he dies in strange circumstances, Jacob, after much hemming and hawing and puttering around (Too much, really; this is where the taking-too-long-to-get-to-the-good-stuff happens), finds his way to the peculiar world. Where he discovers several important things. First is that peculiars live in time loops, which are single days that repeat endlessly; time loops are difficult to get into and thus excellent protection. They are created and maintained by a special sort of peculiar called an ymbryne, in this case the titular Miss Peregrine. The second is that the peculiars live in these loops largely because they are being hunted by terrible creatures called the Hollowgast. Finally, number three: the fact that Jacob can get himself into this time loop proves that he, too, is peculiar, as his grandfather was, because this particular loop was the one that sheltered his grandfather sixty years ago when he was a young peculiar on the run.

Once we get into the peculiar world, the book takes off. There is intrigue, there is action, there is even romance, though it is more than a little creepy in this book because Emma, the young peculiar beauty who falls for Jacob, was once in love with Jacob’s grandfather. Because she has never left the time loop, she hasn’t aged, but the characters talk about how much Jacob looks like his grandfather, and that is clearly the beginning of Emma’s feelings for him. Jacob notes this, but then blows it off because Emma is really hot. And, well, okay, I was a teenaged boy once and I agree that the creepiness wouldn’t stop him; but it’s still weird to think about.

The book ends on a serious cliffhanger, which was something of a problem for me because I actually bought and read this a few years ago, and was irritated by the ending; but now that the other two are published and available, the ending of this one isn’t a problem. Because we can go straight to:

Book II: Hollow City

There are some parts of this book that are fantastic. Most of it takes place in London in 1940, during the Blitz, and those scenes and descriptions are wonderful. The characters from Miss Peregrine’s Home, now that they have left their time loop on their quest (the cause and goal of which I don’t want to give away; basically they are trying to save someone), become fully fleshed out and fascinating characters; there are several other characters encountered along the way who are also extremely interesting, particularly Addison, the talking peculiar dog. I thought including peculiar animals was an excellent choice, though the emu-raffe was one of those uncomfortable stretches based entirely on a particularly funky photograph. The Hollowgast are very much at their scariest in this book, both the more monstrous creatures that do the actual hunting and killing of peculiars and the ones who are able to blend into human society and use it to their advantage — in this case, infiltrating the military of both England and Germany, and using the war as a cover to track down the peculiars. The action in the book is non-stop, and generally well-done; it gets perhaps a little too breathless at times, when the characters comment about how exhausted they are and yet go on to fight and run and fight and run for another few chapters; but it’s a fast read because of this.

The not-great parts are the scenes with the gypsies, who felt badly shoehorned into the story partly because the author had a whole set of photographs he wanted to use, none of which fit into the narrative very well, and partly because gypsies are awesome. And I agree, they are awesome, but they are not well done in this book.

And I hated the ending. There’s a twist, and it’s a heck of a surprise, but it isn’t a good surprise. The bad guys make out too well in this novel as a whole, and I didn’t like it.

You know, it really is a lot like The Lord of the Rings, because The Two Towers, like Hollow City, is the darkest book, where the bad guys seem to be winning pretty much all the way through. (Though there’s a great scene when the good guys win, just like Helm’s Deep: all I’ll say is, Hugh rules.)

But I will also say this: the development of Jacob’s peculiar gift is outstanding, both in this book and in the next. Well, at least the first half of the third book. Before it all goes weird.

Book III: Library of Souls

The ending of the second book is also a cliffhanger, but don’t worry; this book is the end, and wraps up the whole tale.

Unfortunately, it doesn’t do it very well.

Most of the book is great: the Devil’s Acre is the best setting in the whole series, and the way the characters get there and make their way through it was some of the best reading in all three books.

But then there were some real let-downs.

The characters do manage to get into the stronghold of the Hollowgast, and while getting in there is suitably difficult, as soon as they are in, it’s like the bad guys just disappear: the characters are able to roam around at will, finding their friends, freeing them, having really no trouble at all as they actually reach the goal of the quest that started in the first book. It’s a terrible anti-climax, honestly.

Then things get good again, because Jacob turns out to be a royal-class, no-holds-barred badass, and the way his power makes him a badass, and the way he discovers it, and especially the way he uses it, are all completely awesome. Best fight scene in the whole series, right there, and it’s not a short one.

But then it all goes south. Completely. We find out the reason for the Hollowgast’s attempts to wipe out all peculiars, and it’s not the reason we thought, not exactly; and the real reason is really pretty stupid. You see, the Hollowgast were once peculiars, but an experiment in which they attempted to make themselves immortal/all-powerful went wrong (And I just have to say: sci-fi/fantasy people have to stop using the Tunguska blast as a reference point. Seems like every series I read that can fit the timeline has to throw it in there. “And they tried to do some huge ritual, but it all went wrong — and there was an explosion in Siberia in 1906 that was heard around the world!” Yeah, okay. Move on. Somebody use Krakatoa or something, please?) and turned them into monsters. Cool. I like that. But at the end of this book we find out that the experiment was actually a trick, and the real thing that was being sought by the leaders of the Hollowgast-to-be is just — well, dumb. It’s a dumb idea, and the idea that this thing still exists but isn’t in use, and the idea that Jacob is the key to making it work and that it somehow ties into his peculiar ability but how exactly is never explained, and the way the bad guys get to the final scene and what happens there? All bad. Really. None of it is good.

It’s as if Frodo and Samwise get to Mount Doom, and they find out that Sauron is actually just Gollum in a cloak and a fireproof hat, and Gollum (who has pretty much no power at all, and yet somehow they are afraid of him) shakes his fist at Frodo, who hands over the ring without even an attempt at resistance even though it’s just freaking Gollum, and then while Gollum is capering around, suddenly turned into a hugely powerful bad guy by the ring, Samwise walks right up behind him and shoves, and Gollum falls into the lava, and the good guys win. You know: all a letdown, no final tension, no real danger, no real fight; just a twist that wasn’t needed, and then boom — the good guys win.

And then, just like the final chapters when they all go back to the Shire, Jacob goes back home, leaving behind the peculiar world he has fallen in love with, and which we have too. And the home he goes back to still sucks! Just like it did in the first book! And he spends way too much time in the suck-world before things do finally work out in the end.

So how was it overall? It was — good. The peculiar world and the Hollowgast are both good ideas, generally well-realized. The action, which takes up the majority of the books, is extremely good. Jacob and his friends are good characters. The various settings, particularly the ones the author can really play with because they are time-loops, are cool. The theme of the found photographs is unique and inspired, and generally really effective and fun to read.

I just didn’t like the last third of the last book. The very end is okay, but it didn’t make up for the actual conclusion to the overall conflict between the peculiars and the Hollowgast. Really too bad.

So I’d recommend reading the first one, see how much you like the world and the found photographs; and decide if that will carry you through a bad ending. If it will, read the books and enjoy the good parts while they last. I did.