So first, here’s a sneak peek of what’s coming up on the blog:

More ranting about education.

But you knew that already. More specifically, I will be posting about standards, because I hate and oppose those little buggers, and I think more people both would and should if they thought about them the way that I do. I will also be posting about how school administration imposes new expectations and demands and responsibilities on teachers, in the form of new programs that get added every year, without ever taking away any programs or recognizing that teachers are already overwhelmed. Both of these posts are intended as foundations for a post I want to write about censorship in schools: because my colleague recently had to fight to get In Cold Blood by Truman Capote approved for her class for seniors.

Why did she have to fight? Because the administrators worried that the book would be too graphic and disturbing for students. That’s right. The book written in 1965, which does describe the murder of a family and the crime scene afterwards, is somehow going to be upsetting to students — seniors — who listen to true-crime podcasts, who watch horror movies and cop shows and more true crime documentaries. And that book is somehow more objectionable than 1984, with its scenes of torture, and Night and The Diary of A Young Girl with their (also historical and non-fictional) accounts of the Nazi occupation and the Holocaust, and every Shakespeare play ever with all of the murders and suicides and dirty jokes (And sexism and racism and so on, but that’s beside the point, right?), and The Iliad and The Odyssey with all of those multiple murders and sexual assault and misogyny and cannibalism and Hell and so on; and The Things They Carried, by Tim O’Brien, which is about the Vietnam War and includes a scene where two soldiers have to scrape the remains of their friend off of a tree after he gets blown up by a mine. All of those books are on the approved reading list.

I was trying to decide between the first two options, standards or new programs, when something happened: and it combines both problems. As part of the fallout from the tussle over In Cold Blood, there was a meeting yesterday with the faculty of my school and the academic team, who preside over all curricular decisions for the whole charter network, which comprises seven schools in two cities.

Now I have to write about that meeting.

So here’s the deal. The school system I work for is moving to Standards-Based Grading. At all schools, at all levels. The move has been discussed frequently for the past couple of years, always with caveats where I and my fellow high school teachers were concerned: Don’t worry, we were told. It won’t happen for a long time, we were told. It’s only going to be the elementary schools that do it. Welp, there’s been a change in leadership, and now the decision has been made: all schools, all levels. Next school year. So I guess that shows you how much you can believe people who tell you not to worry.

Standards-Based Grading, referred to in the acronym-manic pedagogy system (Hereafter to be known as AMPS) as SBG, is the idea that students’ grades should reflect their learning and their skills: not their work. The basic idea is that grades, rather than being applied to the level of completion of assignments — “You did half of the problems on the math homework sheet, Aloysius, so you get half credit. Sorry.” — should be applied only based on level of mastery of the specific standards for the class, according to a single summative assessment (Though there are caveats there, too. Don’t worry.): “You got 80% on the quiz, Nazgul, so you achieved Proficiency in the standard. Kudos.” Whether Nazgul completed the homework or not is irrelevant; she was able to show proficiency on the standard, and so she gets a passing grade for that unit, for that standard. If she continues to show mastery of the standards, she will earn a passing grade for the class, regardless of the work she completes other than the actual assessments.

Now. The idea of this is to make grades reflect the students’ actual learning and mastery of the key skills, the standards. How the students reach mastery is not the point: which means, proponents of SBG say, that a student is not penalized if they cannot complete work for reasons other than ability (such as they have too many other obligations, too much other homework, they get sick, they don’t have materials, etc.), and students do not have to waste time doing homework when they already know the information, have the skill, mastered the standard; which in theory streamlines education and stops making it feel like a waste of time and an endless grind for the students. The academic team was big on advocating for those poor, poor students who are ahead of the class, and who are bored with work when they already understand the concept and have the skill in question. (By the way: boredom is good for you.) It would also reduce the workload for teachers, because we wouldn’t have to grade all that homework and stuff; and as a sop to teachers who don’t like being told what to teach or how to teach it, with SBG we would have freedom to use whatever content and whatever teaching methods we wished, so long as the assessments and grades for the class focused on mastery of the standards.

That’s the ideal. And in some cases, it works: there are examples (usually cherry-picked, but nonetheless real) of SBG being effective. It is more common at the elementary level, because it makes more sense there to have students’ grades focus on mastery of skills; elementary report cards always have: remember how you got ratings in various traits, which were added up sometimes to a letter grade or the equivalent? But there were no percentages, no test scores averaged with quiz scores averaged with daily bell work scores. Just “Dusty does not play well with others. Dusty’s reading is exemplary. Dusty’s Nerdcraft is LEGENDARY.”

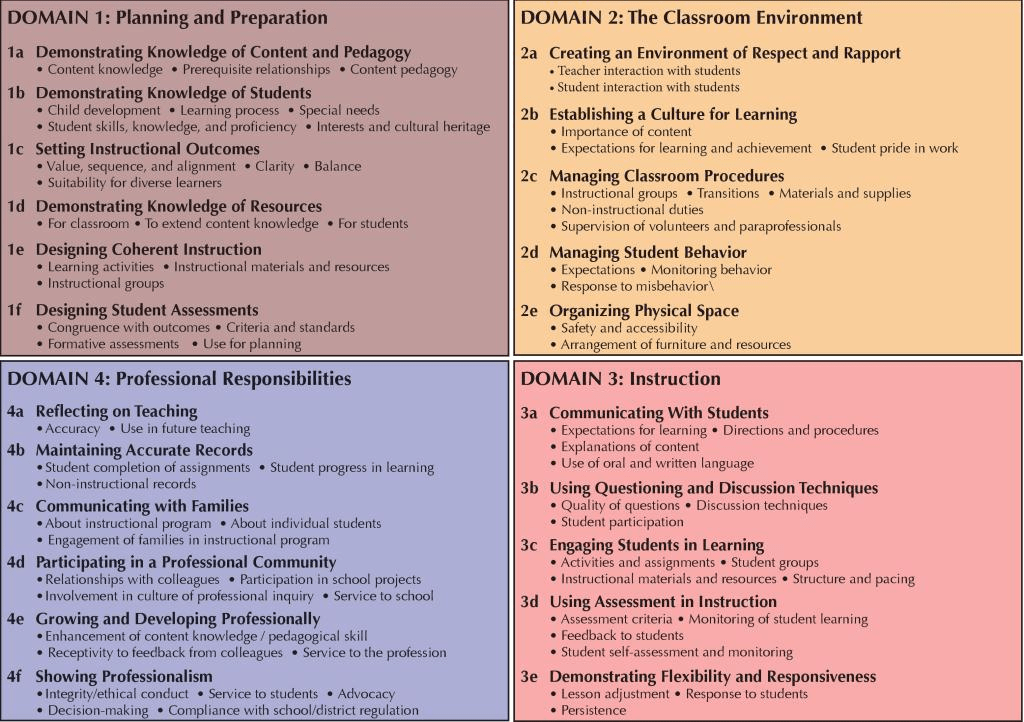

So what they want is for me to teach students, say with a short story, but really (they tell me, adding, “Don’t worry”), it could be anything, a poem, an essay, a full novel, about how to Analyze how complex characters (e.g., those with multiple or conflicting motivations) develop over the course of a text, interact with other characters, and advance the plot or develop the theme. Or as we call it in the biz, Arizona Reading Literature Standard 9-10.RL.3. And then after I have taught them — or, really even before I’ve taught them, because one of the selling points of SBG, remember, is that it allows students to avoid doing unnecessary work when they already know the information or possess the skill — so before I teach them, I would give them a pre-assessment (They like the term “assessment” much more than the word “test,” and they are quick to tell us that the assessments don’t have to be multiple-choice quizzes, Don’t worry,) to see if they already know the standard, and then teach them, and then give them a post-assessment to see if they have mastered the standard after the instruction. Those who master the standard, on either assessment, get a passing grade.

See how nice that looks? How simple it is? Just two required assessments, and you have a complete picture of which students learned what they were supposed to learn, and which did not. None of that muddy water that comes from Student A who does all their work and yet can’t pass the test — but passes the class because they do all their work, and then graduates from the class without having mastered the actual skills — and Student B who does none of their work but who can ace the assessment, either before or after, because they already know how to analyze how complex characters develop over the course of a text. (Don’t think too much about the students who pass the pre-assessment and therefore don’t need to do any of the instruction in the unit, and who would therefore sit and be bored… there’s a whole lot more to say about this aspect, and I will.)

So that’s SBG. And according to my district academic team, it is coming, soon, and it will affect every teacher, including me. And, they said, they hope it will make things better: it will give us a laser focus on the standards. It will make grading more representative of students’ actual growth, as measured by mastery of the standards. It will simplify grades, to the satisfaction of all concerned, teachers and parents and students as well as the state Department of Education, which mandates that all schools teach mastery of the standards they set, and assess a school’s success rate using standardized tests of standards mastery — in our case, as a high school in Arizona, using the ACT, one of the College Board’s premier college application tests (the other is the SAT), which tests all 11th grade students in Reading, Writing, Math, Science, and Writing again (The first one is a multiple-choice exam of grammar and style questions; the second writing exam is an essay the students write for the exam.). They’re sure this is the right way to go.

Don’t worry.

As you can tell (And if you’re a teacher who has heard of or dealt with SBG, you already knew from the moment I mentioned the topic), I am worried. Very worried. As were the majority of my colleagues, from all subject areas, who came to the meeting. The purpose of the meeting was for us to ask questions and voice our concerns with this move to SBG, and we had a lot to say.

The academic team, however: not worried at all. They are confident. And every time a question was asked or an objection was raised — and there were several, which I’ll address here — the response from the academic team was, essentially, “But that’s not really going to be a problem, so — don’t worry.” Or, “That potential issue won’t matter as much as this improvement we expect to see, so — don’t worry.” Or, “We think that question shows that you don’t understand what we’re talking about, or that you are somehow against students learning, so — shut up.”

That last sort of response? That was an asshole response. It happened more than once.

But that’s not the issue here.

The issue here is SBG. The first question, the first worry, is: why are we doing this? Why make a change away from traditional grading, and why is this a better system? The answer according to SBG proponents is what I said earlier: SBG focuses more on student achievement of the standards, rather than completion of tedious and repetitive homework, like math worksheets of hundreds of similar problems, or English vocabulary assignments that require students to just copy down definitions or memorize spelling. SBG is simpler and more streamlined. There is also a stronger focus (“Laser-focused” was the phrase that our chief academic officer kept using; but he has a doctorate in optics, so of course he would enjoy a laser metaphor. [If you’re wondering why our chief academic officer has a doctorate in optics instead of education, well. I can’t talk about it. Or my head will literally explode.]) on the standards themselves, rather than on old models that focused on content: as an “old school” English teacher (Sorry; that made even me cringe), I think of my class as organized around the literature: the first quarter we focused on short stories, and now we are reading To Kill a Mockingbird; next semester will be argument essays featuring Martin Luther King’s “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” and then drama, most likely The Crucible, and poetry. What SBG will do, it is to be hoped, is force me to focus instead on the standards: because proponents of standards believe that standards should be the goal of education, rather than completion of units, rather than a goal based around something amorphous and unassessable, like “Students will understand and appreciate great literature.”

I have a response to that. And when I write about standards, and why I hate those evil little gremlins, I will explain.

For now, put it aside: SBG proponents believe that focusing grades on the standards will focus both the teachers and the students on the standards, and therefore improve the students’ ability to master those standards, because the instruction will be more targeted and specific, and because the students will be more aware of what is expected of them, and therefore will try harder to achieve exactly that. Obviously if mastery of the standards determines their grade, then they will try to master the standards.

Our academic team, when my colleague asked why we needed to change to SBG, said that it was forward progress. When she asked more explicitly what in the current system was broken, what was wrong, which necessitated this change, she was told that nothing was wrong; this was simply a better system, for the reasons listed above.

She was also told (along with the rest of us, of course, because we were all in the same meeting) some bullshit: we were told that traditional grading systems are unfair, because the standards that define a grade for a specific teacher are malleable and individually determined. If you give five teachers the same assignment, those five teachers will grade it five different ways. One will focus on the correct answers; one will focus on the student’s process for reaching the answers; one will focus on the neat presentation of the work. All different standards, all different grades.

Remember how I said that they told us not to worry because not all assessments for mastery of the standards had to be multiple-choice-type quizzes or tests? Right. That was because more than one teacher asked about assessments like essays, or labs, or long projects, or large unit tests, rather than single-standard, short, multiple-choice style tests. “Of course you can use any assessment that you like,” we were told. “Don’t worry, we don’t want to force you all to give nothing but multiple-choice tests to the students.”

Shall I mention here that the curriculum which the academic team purchased and imposed this year features short, five-question multiple-choice tests as assessments for all of the standards? Shall I also mention that this curriculum doesn’t apply to any subjects other than math and English — also known as the tested subjects? No, you know what, I’ll wait until later to mention that. Forget this paragraph for now.

We were also told, when my friend also objected that the purpose here seemed to be test preparation, that of course we should be focusing on test preparation: the school is rated according to the results of the ACT (and other standardized tests for other grades); and research shows (They are big on research. Less interested in actual experience teaching, but they do love them some research. Our chief academic officer has also never taught. [Head. Will. Explode.]) that one of the best ways to improve student scores on standardized tests is test practice: exposure to the system of the test, familiarity with the format of the questions and the means of providing the answers (Bubble sheets vs. writing numbers in boxes vs. clicking on options on a screen, and so on, so on). So if one of our goals is to improve the test scores (And the administrator answering this objection asked my friend if she wanted to have our scores go down, and then the school’s rating would go down, and then we would lose students and close, and did she want that? Which, of course, is a belligerent attempt to turn an uncomfortable question back on the person asking, using a strawman argument. It’s bullshit. It’s not a response to a question, it’s not what it looks like to hear someone’s concern. Because the academic team doesn’t listen. Did I mention that the point of the meeting was, ostensibly, for the academic team to hear our concerns and answer our questions?), and test scores are improved by practice with similar testing format, and the assessment test in question is the ACT, which is a multiple-choice test: guess which type of assessment is going to be favored by the academic team?

It ain’t essays. Or projects. Or labs. Or large unit tests. Well — essays will get some respect, because one of the sections of the ACT is an essay. But there aren’t any, for instance, poetic recitals, or creative writing, or music performance, or any of the million things that teachers and schools create so that students can do something more than just bubble in A, B, C, or D. You know: the assignments and projects and grades which mean something, which give students a chance to make something important to them, something authentic, something real.

So this is why what they told my friend was bullshit: because if they really meant that we could use various other forms of assessment, so long as those assessments focused on the assigned standard, then they were lying about SBG being intended to make grades more fair. If their argument is that different teachers will focus on different aspects of the same piece of student work, and make different grading decisions about that same work, then the exact same thing will still be true if we grade according to a standard. Because it is still up to an individual teacher what it looks like when a student achieves mastery of a standard. Also true for a multiple-choice quiz, by the way: because what is “mastery?” 60% right? 80%? 75%? Different ideas of proficiency, individual standards of success. Which, by the way, reflects everything else in life, because our success or failure is generally determined by individual people with individual standards of success. And the way we deal with that is not to try to standardize everyone into adhering to a single standard: it is making sure we understand what the measure of success is, and how we can achieve it. You know: learning what your boss wants from you and then providing it? Does it matter if the bosses at two different jobs have different expectations of you? It does not. So why would it matter if two different teachers have different expectations of you? It does not. To be sure the grading is fair, we need to make sure that the teacher consistently applies the same standards to all of their students. That’s fair.

You can address that issue, by the way, if you want all of your teachers to grade according to the same criteria and the same success expectation. But SBG is not how. You need to bring your teachers together, give them the same piece of work, and discuss with them what grade (or proficiency measure, or whatever you want to call it) that piece of work should receive, and then make them practice until they all grade approximately the same way. It’s called “norming,” and I’ve done it several times, in different contexts. It’s actually good practice, and I support it.

But it doesn’t answer my friend’s question about why we are changing to SBG. Because you can (and should) norm while retaining traditional grades. Using the need for norming as a justification for changing the entire system? Bullshit.

There’s another aspect of the change to SBG which I should maybe mention now, though I realize that this post is getting too long. (It was a long meeting. There were a lot of concerns. I have a lot of worries about this.) They are also intending to eliminate the usual percentage-based grades. There are four levels of mastery of a standard, as determined by the Arizona Department of Education: Minimally Proficient, Partially Proficient, Proficient, and Highly Proficient. The academic team wants to use those four as the new grade scores, for the purpose of averaging into a final grade for a course: 4 for Highly Proficient, 3 for Proficient, 2 for Partially and 1 for Minimally. The student’s class grade will therefore be something like a 3.23, or a 1.97, etc. Sure, fine, whatever; it’s not like I need to use A, B, C, D, and F.

But see, they want to translate those numbers back into letter grades. Because students and parents like letter grades. Because (As was mentioned, as yet another concern, by yet another colleague) colleges, and scholarships, use letter grades — or, more frequently, the overall GPA, weighted and unweighted, that is the standard across this country. So that’s fine, right? We can just translate the proficiency numbers directly: Highly proficient, A, 4.0. Proficient, B, 3.0. Partially is a C, Minimally is a D.

There’s the first issue, by the way. Not Proficient is not an option. Which means there is no F. As long as a student takes the assessment, they will pass the class. Or so it seemed to me: I admit I didn’t ask that question or raise that concern; in fact, other than a few outbursts under my breath, I was silent throughout the meeting. Because I knew if I started talking, my head would explode. That’s why I ranted at my friend for a full 30 minutes after the meeting, and why I’m writing so damn much right now. So they may intend to include Not Proficient, or simply Failing, as a possibility; say if someone takes a test assessment and gets a 0, then they might earn an F. But maybe not. It’s a concern.

But the other problem is this: the academic team has a conversion chart they want to recommend for how to turn this 4-point proficiency scale into a letter grade: and it’s not what you think. They think that a 3, a proficient, should be an A-, a 90%. 4, Highly Proficient, should be an A+, a 100% or close to it. The B grade range should be 2.5-2.99, the C would be 2.0-2.49. D would be 1.00-1.99. (F would, presumably, be 0-0.99, but if there is no score less than a 1…)

I mean, sure. You can set the grade breaks anywhere you want. They did point out that any college asking for our students’ transcripts and so on would be given an explanation of how we arrive at their letter grade, so there would be transparency here. But how many colleges or employers or grandparents looking to give money prizes for every A would actually read the breakdowns? When they are handed a simple overall GPA, in the usual format?

I also have to say, because bullshit pisses me off, that one reason the academic team gave us for the change to SBG was that traditional grading leads to grade inflation: because students who do extra work get extra credit, and therefore score over 100%, which makes no sense if we’re talking about mastery of standards, because once you master it 100%, that’s it, there is no more, and how much work you did to reach mastery doesn’t matter. The standard of mastery to earn a particular letter grade, in this paradigm, is watered down by the inclusion of grades for practice work, what are called “formative assessments.” Think of it like a rough and final draft of an essay for English: when I get a rough draft of an essay, I give feedback on the draft so the student can improve it for the final draft. I give credit for students who completed the rough draft, but it’s just a 100% completion grade: because I want to encourage them to try, and to turn in whatever they complete so they can get feedback, even if it isn’t very good. So I don’t grade the rough draft on quality, just completion. The rough draft grade is a formative grade; it’s just to recognize the work a student put into the rough draft. The final draft grade is the one that “counts,” because that’s where the student shows how much they mastered the actual skill and knowledge involved. That’s called a “summative” grade. SBG would only count summative grades into the final grade for the class. And in order to fight back the grade inflation they see in me handing out 100% grades to students just for turning in a pile of garbage they call a rough draft, they want to change to — this system. Where a 3 is magically turned into a 4, and there is no 0. Nope, no grade inflation happening there, not at all.

And that’s my biggest issue here. Again and again, the academic team told us that the only thing that should matter for a grade is mastery of the standard. Nothing else. No work should ever be graded, because how a student achieves mastery is not the point: only mastery. (Sure. Ask any math teacher if how you get the answer matters, or if it’s only the answer that counts.) They told us that grading for work completion is a waste of time, and essentially corrupt; because it made it possible for a student to pass without mastering the standard.

The essential assumption there, aimed without saying it outright in the face of every teacher in every school, is that the work we assign does not create mastery of the standard. The assumption is that when I give vocabulary homework, it shouldn’t count in a grade because whether a student does it or not makes no difference to their mastery of the standard. In other words, all the work I assign is bullshit, and any grade I give based on completion of it is bullshit.

That. Is. Not. True.

More importantly in terms of what is coming for my school, if a student is told that the homework, the practice work, the rough drafts of essays, are not counted into their grades, they will stop doing them. Of course they will: we just told them those things don’t count. All that counts is the final assessment, whatever that is. It wouldn’t matter how much practice I gave them, how much feedback I wanted to give them; I would have to give all my students an opportunity to show mastery on the final summative assessment, and if they showed mastery, they would get a grade for that standard. A high one, if they showed proficiency. Now, they will have a much harder time reaching that proficiency without the practice work I assign in class: because my assignments are not in fact pointless busywork, I fucking hate pointless busywork and I try very hard not to have any in my class; but regardless of the value of my assignments, if my students don’t get a grade for them, they won’t do them. Period. Except for a very few students who want to try hard, who want to learn, who want to do their best. But those students already succeed, so they’re not the ones we’re trying to help here, are they?

You know what the rest of them will do? They will sweat out the final assessment. They will focus on that. They may study for it, but they will have so much pressure, and so much stress, before any test I give them for a particular standard, that they will not do as well on them as they would with traditional grades and grades for practice work and my own non-test assessments. (Because generally speaking, I also hate tests and try very hard not to have any in my class. I like essays. I like personal responses to questions that ask the students to relate to the literature, to connect to some aspect of it, and to write maybe a paragraph or so. I like annotations on literature, so students interact with the text. I think high school English students should write, as often as possible, and when I ask students to do work in my class, I want to recognize their effort by giving them credit for it in the form of a grade. But I guess that’s unfair grade inflation, right? Busywork? Assignments that don’t show mastery of the standard and so shouldn’t count in their grades?)

I also have to point out that a lot of my students, given the opportunity to do literally no work and then take one assessment to determine their grade in the class? They will guess. Some of them may guess well, but they will guess. Stories will spread of the students who guessed their way to an A on a difficult assessment in a difficult class, and others will try to repeat the feat. I know: I’ve seen them do it. I’ve watched students lie about getting high grades, when they actually got low grades, when they guessed on a test, and that lie made other kids try it. I’ve watched brilliant students describe what they do on tests as “guessing,” when what they mean is that they picked an answer they weren’t 100% sure about: after reading the question, the answer options, using the process of elimination and their generally excellent knowledge to narrow it down to only two good choices, they “guess.” And score high, because that’s actually a really good way to “guess.” But when they say they guessed and got a good score, other students, who are not as brilliant, guess by completely randomly picking a letter, and hope to get the same result — and so ruin their chances of getting a good result, or a realistic result, which they would have gotten if they just tried.

This will make that problem worse. I guarantee it.

And what problem will it solve?

Will it make grades more fair? No: that would take norming.

Will it make grades actually reflect learning? No: students will try to guess and get lucky, or they will cheat. They already cheat, sometimes, but SBG in this model will make it worse because there will be so much weight on single assessments.

Will it make students focus more on mastery of the standards? Maybe, but it will also make them more likely to ignore the work that would actually help them master the standards. You know: the stuff that educates them. Which, yes, is sometimes tedious. Kinda like taking multiple-choice tests several times a week, in all of your classes. But I guess if that helps them score higher on the ACT, then the school is going to look great. Right?

Right?

Don’t worry.

There’s more. Here’s where I should bring up that the curriculum they bought and imposed doesn’t have any material for several of the subjects in the school. That’s sort of a separate issue, because any teacher can create their own curriculum using SBG or not; but whenever teachers asked how we were supposed to implement this, we were pointed to the curriculum and the resources that came with it: which only applies to math and English. The tested subjects. There are also classes, such as my AP classes, and the new electives that we created this year, which don’t have any standards because they are not official Arizona Department of Education classes. And that’s why I like teaching those classes: but how will I do my grades next year if every class has to use SBG and the class has no standards?

They also claimed that SBG would make grades and student learning more clear to parents, that parent teacher conferences would focus on what the student could and could not do, rather than the teacher merely saying “Little Tikki Tikki Tembo-no Sa Rembo-chari Bari Ruchi-pip Peri Pembo is missing three homework assignments.” Of course, speaking for myself, when I have parent conferences, I EXPLAIN WHAT THE STUDENT SHOULD HAVE LEARNED ON THE MISSING ASSIGNMENTS AND HOW THAT LEARNING CONNECTS TO THE OTHER LEARNING IN THE CLASS, LIKE “When Tikki Tikki Tembo-no Sa Rembo-chari Bari Ruchi-pip Peri Pembo didn’t do the study questions for the first three chapters, that means he probably didn’t completely understand those chapters, and that makes it harder to understand the rest of the novel.” (Though of course, I failed to point out the standard which little Tikki Tikki Tembo-no Sa Rembo-chari Bari Ruchi-pip Peri Pembo didn’t master, so — my bad.) I can’t really fathom a teacher telling a parent the number of missing assignments and then not going on to explain what that means; but that’s how the academic team described our current practice, going on to say that SBG would make those conversations more helpful to parents because we would explain exactly what the student knew and didn’t know, exactly what deficits there are. Which means that their current (apparently, in their eyes, deeply incompetent teaching staff) would change our habit of explaining nothing to parents so long as we had better data to point to.

And one of the staff very intelligently and clearly pointed out that we would be setting students up with a different standard from all the rest of the world, even if everything they hoped for regarding SBG happened exactly as they hoped: because in college, they still use traditional grading, with work counted in the final grade, with individual standards of success and personal bias from the professor. They didn’t listen to her, either.

They told us that we teachers would be helping the academic team to chart the course, that our input would have an effect on the way this process moved forward; but since they didn’t actually listen to any of our questions at this meeting, and they told us that SBG is coming in 8 months regardless of anything we may say, here’s what I have to say to that:

The only times that the academic team agreed with anything the teachers said was when one of my colleagues, and then another, pointed out that parents and students — and teachers — would have a very difficult time adjusting to this entirely new system, and there would be a lot of problems in the transition, and a great need for support. “That’s true,” they said.

But you know what support we will get? We teachers, our students, their families, the whole school community?

“Don’t worry.”