With many layers. Like an onion. (I’d say “Or an ogre,” but I love Shrek and I won’t bring him down to this level. [Spoiler: I am absolutely going to bring Shrek down to my level. And then sit on him.] But here’s the clip anyway:)

I love Shrek because I relate to everything about him, from his introversion, to his grudging love of humanity, to his deep love for his wife, to his lack of self-esteem combined with an awareness of his strengths and abilities. I appreciate Shrek because he’s a Republican. Honestly. At least, he’s what Republicans should be. (And I don’t mean to ruin Shrek for anyone with this comment, but also, if more Republicans were like Shrek, we wouldn’t have the partisan problems we have now. But noooo, we get the other, uglier, eviler ogre. Ah, well. This isn’t the point.) Shrek is definitely a conservative: he dislikes and distrusts big government, he doesn’t like change, and he wants to be left alone. He’s the NIMBY in all of us. Though that should be NIMS, No’ In Ma Swamp, of course; and I mean that for all cases and circumstances (Though again, the other ogre has sort of ruined the rhetorical use of “swamp.” What an ass. He’s like the anti-Shrek. He doesn’t even have any layers.), because if I ever go to a city council meeting to object to them building a prison in my neighborhood, I’m definitely going to channel Shrek defending his swamp.

But if anything is likely to turn me from a progressive into a Shrekian conservative (Definitely not going to become a Republican right now: the party is just too toxic. But also, if Shrek ran for office, I’d vote for him over most mainstream Democrats I know of.), it’s the layers in the sandwich of modern education. The layers in the onion.

Definitely not a parfait.

See, here’s the thing. I’m a teacher, right? We all know this by now; I talk about little else on this blog but books and teaching. But what does that mean, being a teacher? I’ve fulminated and pontificated over this many a time, because if there’s one thing that is clear about teaching, it is that it isn’t clear what teaching is; but the basic concept is pretty simple: it’s right there in the name. I teach stuff. I stand in front of a bunch of people who don’t know some stuff, and I help them learn that stuff. In my case, the stuff is literature, which is another complicated, amorphous concept that isn’t easy to define; but once more, the basic idea is really quite simple: written stuff, words and stuff. So basically, I help people who don’t know word stuff to learn more about word stuff.

Gonna need that on a business card, please.

(I bitch about it a lot, but right now? I thank all the gods there ever were for the internet. Because check this out. I made this on an instant business card generator on the internet, and I love it.)

Eighty or a hundred years ago, this could basically have been my card. It wouldn’t have had Shrek, so it would have been much less awesome, and the font would be much more calligraphic; but basically, it could have said this, and everyone would have nodded and doffed their bowler hats respectfully.

But then in the last fifty or sixty years, things started changing.

Obviously I am taking too broad a view of the history of pedagogy and education to be able to clearly identify causes and effects; there have been far too many influences and impacts on the education system in that time for any one to stand out. But I’m still speaking simply, broadly, in fundamental ways: and sometime over the last two to three generations, educators realized something: education wasn’t working for everyone. And also, that that was a problem.

So they tried to fix the problem.

It makes perfect sense: prior to about the WWII era, the problem was that not everyone had access to education; so the major push in the country was to build schools and hire teachers and buy books and such. But in the war years and the post-war boom, most of that got accomplished; and so the focus changed, from spreading education, to improving education.1954 saw the Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas decision from the Supreme Court, and that threw into stark relief the clear truth that not all schools were equal, and also that people who did not have access to an equal education were in trouble. Title IX in 1972, and the Education for All Handicapped Children Act of 1975, which then became the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, along with the Americans with Disabilities Act, in 1990, helped to show that race was not the only reason why some people were denied equal access to education. And somewhere in there, we reached a point where everyone had access to school (Though obviously as this is still not true, particularly in rural areas and especially affecting indigenous and Native American children, I’m not covering the whole story: but I’m not covering the whole story.), and so at that point, where broadening inclusion into education became less of a concern, people started looking more at the quality of education that everyone in this country now had some sort of access to — part of that fight being the specific issues I have named, making sure that people of all races, genders, and abilities had equal access to education. Because once everyone gets something, which is always the first fight, then you try to make that thing better for everyone. Hence, reform.

In 1955, Rudolf Flesch published Why Johnny Can’t Read — and What You Can Do About It.

It was a bestseller for — no kidding — 37 weeks. In my own shallow understanding of the history of education in the U.S., I’m going to identify this as one of several flashpoints, points when people started looking seriously at the deficiencies in the education system, and started trying to plug the holes, fill the gaps, bandage the wounds. If you look at that image, you see one example of what I’m talking about: the top banner text there calls this “The classic book on phonics.” There: that’s one thing, one example of what I’m talking about. Not the first, I’m sure; if this isn’t the right era and the right flashpoint to identify, I should probably go back to John Dewey, who singlehandedly broke down and then rebuilt American education in the first half of the 20th century. But I think for quite a long time after that, people were still just — helping people who didn’t know word stuff to learn more word stuff. I don’t think they were doing as much to discover the gaps in some people’s learning of word stuff, and trying to figure out how to fill those gaps, or at least stop the wound from bleeding any more.

I’m using the wound metaphor because there’s a metaphor that I and all of my fellow teachers use all the time for this kind of stuff: bandaids. Which is actually where I came up with the metaphor that started this whole mess, this idea of layers, of a sandwich, or an onion. Or an ogre. (Sorry, Shrek.)

Not a parfait.

You see, the issue is, once someone identifies a problem, and then tries to diagnose it, and then proposes a solution to the problem, that leads to — repetition of the same process. Partly, I think, because most solutions proposed for most problems in education are bandaids only: they are a failure to understand the real underlying problem, along with two things: a refusal to admit that the underlying problem can’t be solved — and a refusal to throw up one’s hands and do nothing, since the problem has been identified. That last part is particularly insidious in education: because teachers, who are the ones most likely to become reformers, are used to attacking problems when we see them: and we’re also used to being right. (Look at me, spouting all this “history” without any source or evidence that my account is right. Forget about it: I know I’m right. Because I’m a teacher. So my idea for solving all of this is the right one. Now sit down and start taking notes.) So when we become aware of a problem, we immediately have a solution: and we are immediately going to put it into practice, even if we are running entirely on assumptions. I think that urge, to take action always, and that (generally misplaced — certainly true in my case) overconfidence in our abilities and ideas, means that education gets waaaaayyy more bandaids than other aspects of society that need fixing. Medicine, for instance (since I’m using the bandaid metaphor) is much more likely to investigate and analyze, using the scientific method to find real solutions, and to make change happen slowly, but effectively; schools are just like “That didn’t work? Oh well — here, I have another idea. No no, this is a good one!”

Flesch, an education theorist, had a pretty reasonable proposal here about reading instruction: having recognized that Dick and Jane books were a crap way to learn word stuff, he suggested an expansion of the use of phonics for reading instruction, rather than the “Look-Say” method that had been in common use prior to the publication of his book (Look at the word; now Say the word. “See Dick run. Run, Dick, run!”). Now, I haven’t read the book, but I’m confident that Flesch noted that there was a problem with literacy in this country, that too many people didn’t know how to read, or didn’t know how to read well enough. He identified that problem, and then after examining the education system, he diagnosed a cause for the problem, and suggested a solution. Phonics instead of Dick and Jane. Awesome.

And I bet it worked. Pretty well. In some cases. Maybe even a lot of cases. Which is wonderful, because it meant more students learned more word stuff, and of course that’s always good. Of course, it meant that teachers who had been teaching Dick and Jane for generations had to change: they had to learn better how to use phonics, how to teach phonics, how to explain to confused parents why their kids weren’t learning from Dick and Jane the way the parents had; but I bet it worked.

For a while.

But then they realized that people still didn’t know how to read. Not enough of them, or not well enough. Because then Flesch published this:

That one came out in 1981: because the problem persisted. And why did the problem persist, despite the gains that might have been made — that probably were made — in the area of child literacy, at least partly because of Flesch’s promotion of phonics, which is in truth a pretty good way to learn reading?

Because the problem wasn’t simply a lack of phonics training. It wasn’t just a problem with Dick and Jane. That was surely part of it — which I know because Dick and Jane are gone now, and have been gone for a long time; I don’t specifically recall learning to read with phonics, but I know I never read a Dick and Jane book when I was a child. And I was in 2nd grade in 1981; I could have been that kid on the cover of the sequel, with its “new look at the SCANDAL in our schools.”

I haven’t read this book, either, but I bet I know what the scandal was: it was that some people still couldn’t read, or couldn’t read well enough. And I bet this book has a new proposal for helping those people learn more and better word stuff; whole language instruction, maybe, which was one example of a backlash against phonics teaching. Flesch might have still been flogging phonics in this second book, but plenty of educational theorists have completely reversed their field and gone back on their own pedagogical theories when faced with new evidence that says their old theories were garbage. And that’s good, because you should be willing to change your ideas in the face of new contradictory evidence: but if you just make the same errors in trying to understand and address the problem, rushing ahead with your new idea (“No no, this one’s a good one! Seriously!”) you’re still not going to actually solve the problem, no matter how innovative the idea is you end up on: it’s just going to be a much more innovative bandaid, slapped on top of the other bandaid. And as bandaids are wont to do, it might slow the bleeding for a while: at least for as long as it takes for the blood to soak through the new bandaid just like it soaked through the last one.

But education gaps, and problems that real people face in trying to learn, are not like bleeding wounds, because problems in education don’t clot. They don’t have mechanisms to solve themselves. They do eventually disappear, but that’s because the people who have trouble learning leave school, and don’t show up on our graphs and charts any more. They are replaced by other people who have the same sorts of issues, often because of the same underlying problems.

But the people trying to fix education, trying to fill gaps and stop the bleeding — and also heal the wounds — never recognize the actual underlying cause of the gap, of the bleeding; or they recognize it, but can’t or won’t face the truth and try to at least name the problem, if not address it: which they avoid because they can’t address the problem. Teachers hate when we can’t fix the problem: and what we generally do is address the symptoms, just so we can do something. Like if students come to school hungry, rather than deal with whatever the home life issue is that leaves kids coming to school hungry — lots of teachers just buy and distribute snacks. So when education reformers, largely teachers and ex-teachers, can’t deal with the real issues, instead they find something else they can point to, and some other new bandaid program they can slap on top of the issue, to make it look like it’s going away.

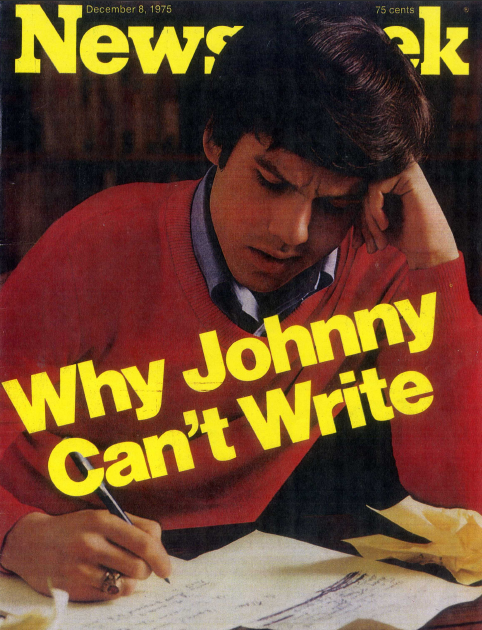

Like this:

I mean, my first theory is that Johnny can’t write because Johnny can’t read.

And please notice that we’re still not really talking about why Johnny can’t read, beyond the idea of More Phonics Training: which is only trying to address one symptom, and ignoring entirely the underlying cause of the gaps in literacy in this country.

Then that leads to this:

Oof. That’s a big one. We still deal with this today. Still not well: I have many students with ADD or ADHD; many of them have had their issues addressed in a dozen different ways. But you know what?

They still have problems.

Because we’re not addressing the underlying issue. Just slapping on bandaids.

And that leads to this:

And eventually, to this.

And here we are, today. With conservative assholes like Sowell (Who, I must say, is clearly a brilliant man and an influential thinker and writer and teacher; but his mentor, when he studied economics at the University of Chicago, was Milton Friedman. The Fountainhead [In the Howard Roark sense] of assholes. And this quote here is an asshole quote.) making asshole pronouncements about what’s wrong with kids these days. And still not looking at the real, underlying problems. Just trying to find another way to slap a bandaid on the problem, and hope that it isn’t visible for a little while: long enough for the person who put forward the bandaid to get paid, or to win an award, or to get a cherry position in one thinktank or institution or another.

Okay: but I’ve strung this along too long without actually making my point. (There’s a reason for that.) So let me make the point, and then I’ll explain why I have done it this way — and also why I mentioned soup in the title of this post. (No, I haven’t forgotten that. It’s okay if you did. I know I am frequently confusing, and you kind people who read my nonsense are willing to put up with me, God bless you all.)

Again, I’m not versed enough on the history of education and education reform to have a strong argument about where this process I’m describing came from, how it got started, and how it came to dominate my profession. I just know what the actual answer is, which nobody ever seems willing to address: and because of that, for the last 23 years that I’ve been a teacher, I have had to deal with unending nonsense, while knowing it was nonsense. It is for this reason that I hate inservice: because I have to spend days being told how we are going to address the problems in education, and every single time, they don’t address the actual problem which is the cause of every difficulty in schools.

Here it is. Ready?

The actual answer is this: the problem is with school itself. And more broadly, with the human race.

You want to know why some people struggle in school? Because school is incapable of addressing everyone’s needs. The whole idea of it is to increase the efficiency of learning, through the use of specialization: that is, since I know a lot about word stuff, I can provide word stuff-centered learning to a large number of children, thereby sparing their parents or extended family members from having to teach their kids word stuff. In the past, those parents or family members did just fine, and better than me in a lot of cases, at teaching kids to read and write; but it’s more efficient if they can send their kids to school, and I can teach 100 or them at a time how to do word stuff. Or 200 at a time, at my last school. Those parents and family members of my 100-200 students can now spend their time and energy doing other things — in this country, mostly struggling to make ends meet while also providing a lavish lifestyle to the parasitic capitalist class who extract wealth from their labor. (I know a fair amount about Marxist stuff, too. I learned it in a class on word stuff in college. But since it was a word stuff class and not an economics stuff class, I can only give a basic overview of the economics stuff. You should find an expert in economics stuff to learn from instead of me. Specialization.)

Is this a better way to learn word stuff, in a classroom with several other students being taught by a word stuff expert? In some cases, yes. In some cases, no. Two of the best students I’ve ever taught were homeschooled up until 9th grade. But the advantage that public school has over homeschooling in whatever form is efficiency: parents can only teach their own kids, and that only at the cost of much of their time and energy. But I can teach a hundred kids all at once. See? Efficiency.

But the only way I can efficiently teach a whole bunch of people word stuff is if those people all learn word stuff in basically the same way, and all of them can learn it from me and the way I teach word stuff.

And of course they can’t.

Some of my students have obstacles to learning reading and writing, such as language disabilities, or simply language barriers because their first language isn’t English, which is the only language I teach word stuff in. I am an auditory learner, and an auditory teacher; and some of my students — many of my students, in fact — struggle with learning that way. But honestly, there isn’t a whole lot that can be done to help a kinesthetic learner, that is one who learns by moving and doing things, to learn word stuff, which is inherently a non-moving and non-doing kind of system. These days, the biggest obstacle to learning word stuff for my students? They don’t care about reading. They like watching videos and playing games. They like livestreams and YouTube and TikTok. They don’t see the point in reading and writing, which means they don’t want to learn word stuff.

What do I do with that?

Nothing, is the answer. It’s just going to get in the way of my students learning my specific subject. Which may not, of course, have any serious negative impact on their lives (Though I will always maintain that a person who cannot read well enough to enjoy reading is always going to be a disadvantage: doubly because they may never realize what they are missing); but it certainly creates a gap in their learning progress according to the measurements we use in this country, which focus on math and English. My students’ test scores will be lower than in past years, because these kids don’t really care. (Also, they don’t care about testing. Or grades, really. Or, well — education.) Also, because I have taught Fahrenheit 451 for decades, I have to restate the thesis of that book, which is: a society that doesn’t read is a society that doesn’t have empathy, and is therefore a dying society. There is truth there. Want to talk about the empathy crisis in this country? (I will write a whole post about this, I think. It will be depressing.)

Which leads me to the other half of the problem, as I stated above, that isn’t caused by the inherent nature of the school system: the human race in general. Not all of us want to learn. Not all of us can learn. That’s just the way we are: we are different, we have different capacities and interests, different wants and needs. When we, as educators ALWAYS do, act as though one size fits all, that one set of goals will work for every single individual and one system of achieving those goals is the best path for every single individual (Specifically, the one that I choose, as I am the expert here. Now sit down and take notes.), our measurements are always going to show gaps and holes and flaws and even bleeding wounds: because not everyone can learn. Not everyone wants to learn. Not everyone can learn or — here’s the big one — wants to learn from me, or from my fellow teachers, in a school setting.

And then there are the other problems that get in the way of people who can learn and want to learn, but can’t do it at a particular time in a particular set of circumstances, and so also show up on our measurements as an issue to be solved, a wound to be bandaged: problems like poverty. Hunger. Illness. Trauma. Abuse. A lack of physical safety or security. Institutional racism or other forms of discrimination. And on, and on.

All of which get in the way of someone’s learning. None of which can be addressed by increasing my use of phonics.

You can see, maybe, why people don’t want to talk about the real problems, or the real solutions to those problems: because often, the real problems don’t have solutions. At least not ones we can implement.

There are people we can’t help. There are people who don’t want help.

That is not to say we shouldn’t try to help. We should always try. If for no other reason, then simply to show people who need help that someone cares enough to try. To show people who don’t want help that, if their wants or their needs change, someone will care enough to try, and help might be available someday which will do some good.

But we have to accept that we can’t fix every problem, and especially not in education. There will always be disparities. There will always be gaps, and failures. It’s inevitable. That’s the truth.

So what’s the soup?

It’s the alphabet soup. Though as my title states, it’s not soup: it’s a sandwich. It’s not soup because the old layers don’t go away: we just slap a new layer on top of it. If it were soup, all the layers would mix together in one thick broth, and that’s not how it goes: the individual layers tend to have enough cohesion to avoid mixing with other layers. So, a sandwich. Or an onion. Or an ogre.

Not a parfait.

Though that is the reason I put that title above, and held off on explaining it until here and now: because now you have been through the layers. And maybe, if you have been confused by my wandering through half a dozen layers that touch on entirely different perspectives and different paradigms and different strategies about different aspects, maybe you will understand what it is like, as a teacher, to try to work through all of these layers — to try to master and implement all of these layers — when I just want to teach word stuff, man. That’s all I want. But they have all these layers stuck on top of that word stuff I want to teach. Layer on top of layer.

Those layers are often called “alphabet soup” because the snake oil salesmen who put them forward in an attempt to enrich themselves by treating symptoms instead of addressing the real underlying conditions are inordinately, eternally fond of acronyms. Everybody in education loves a good acronym: nobody more than the people who imagine they have created a brand-new system whereby schools can solve the problems in education.

See, that’s why I’m not just a teacher who helps people learn word stuff. Because snake oil salesmen are very good at convincing one particularly vulnerable group, who themselves don’t ever want to address the insoluble underlying conditions (Which, to be fair, are so large and so insoluble that it would be like a doctor saying, “Well, the problem is that you’re mortal, and so you’re going to die. Here’s your bill.” On some level it’s worth looking at treating the symptoms. But that’s not what the layers are about. That’s what teachers and other adults in schools trying to help is about. I don’t think it’s a bad idea for teachers to buy snacks and give them to hungry students. I do it, too.), that this new program that the snake oilers have cooked up is the best way to address the problems in education.

Those vulnerable people? Adminstrators.

It’s not their fault; they don’t know any better. They are simple people. They don’t understand. They just want to make a difference and fix things (And also improve their own reputation as people who get results), and when they hear about this new program, with its new acronym, which will treat these symptoms with these provable results as presented in this bar graph? Well hell, sign us up! they say. And here, take this large sum of money, which of course is not the administrators’ money; it’s taxpayer money. It’s so easy to spend taxpayers’ money. After all, we’re just trying to address these learning gaps, these holes in our data, and the blood that just keeps flowing out of them. (Like I said, if anything would ever drive me to become a conservative, it’s this. Bureaucrats spending taxpayer money for no good purpose, with no real understanding of what they’re doing or why: that’s enough to make any liberal go crazy. And here we go.)

So: I’m not just a teacher. I’m also an expert in PLCs (That’s Professional Learning Communities.). And in AVID (Advancement Via Individual Determination — I’m going to a conference this summer to learn more about it!). And in PBIS (Positive Behavior Interventions and Supports — I was on the schoolwide committee for implementing that one.), which I insist on pronouncing “Peebis,” which makes everyone uncomfortable while it makes me laugh. And in SEL (Social-Emotional Learning). And in RTI, Response to Intervention. Naturally I’m an expert in ELA (English Language Arts) and in ELD (English Language Development — what used to be called ESL and then ESOL [English as a Second or Other Language]) and in SPED, which is now becoming ESS as SPecial EDucation becomes Exceptional Student Services (Which some places call ESE, Exceptional Student Education, but I wouldn’t be able to stop myself from saying “Orale, ese!” every time I thought about it. So it’s good my school uses ESS.). I won’t say I’m an expert in ADD and ADHD and ASD and ED (That’s Emotional Disturbance, not Erectile Dysfunction — these are kids, after all) and ODD (Oppositional Defiance Disorder — and while I’m not a Boomer bitching about how we used to walk to school through three miles of driving snow every day, I will say that when I was a kid, ODD was just called “Being an asshole.”), but I’ve been in enough IEPs and 504s and dealt with enough SLDs that I know as much about all of those as most, and more than many. Naturally I can’t get more specific, because I’ve been well trained in FERPA.

This is the result of all of this: I have been given so many additional duties, so many new processes to learn and programs to implement, that I don’t have enough time and energy left any longer to just — help people learn more word stuff. My specialization — the whole reason for a public school system — has been smothered under layers of new generalized knowledge that I have had to master and implement. Because people keep identifying problems, and then prescribing solutions that aren’t really solutions, but maybe have enough of an impact, or at least are convincing enough to make an administrator think the program will have an impact that they spend money on it and implement — which means telling me I have to become an expert in this, and I have to be trained in it and then implement it, and then follow up by collecting data to show how effective this new program is, in order to justify the administrator’s decision to implement it, and the money they spent on licensing it and hiring a trainer to teach me how to do it and a data processing firm to confirm how well it works: provided I can implement it with fidelity and then collect the data on implementation to show how effective that program is. And guess who gets blamed if I can’t do all that on my end: not the snake oil salesman who got my administrator to buy the program, and not the administrator who bought the program — and not the students who spend my whole class scrolling through TikTok.

And if I do manage to do all of that successfully, the snake oil salesman who sold it to my school will then use my example as proof of their program’s efficacy, and go on to sell it to a hundred more schools. And the administrator will either squat in their job for decades, buying new programs EVERY GODDAMN YEAR but never taking away the old ones, because it worked so well that one time and that success ensured the administrator’s retention in their position (Meanwhile my retention depends on my ability to keep up with each new year’s new layer on the onion…), or else the administrator will move up the ranks, and be replaced by a new administrator who will have to buy all new programs so they can make their own individual impact on the problems in school (Also, since most administrators are ex-teachers, they also believe they have diagnosed exactly what the problem is and how to solve it, with this new acronym they bought with taxpayer money).

And my students, and the students at all those other schools, will learn a little bit less word stuff. And other stuff. Which will just convince the students that school isn’t really useful, after all; they’d be better off learning how to make their own Twitch livestream and making a living off of that. Which means they won’t try as hard to succeed in school.

And there will be new learning gaps.

Fortunately, I just heard about this new program to address it.

It’s called GET OUT OF MA SWAMP.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/8d/0a/8d0a1e50-ca73-4db7-87d8-41dd2bc7c1f8/bilbo_comes_to_the_huts_of_the_raft-elves__the_tolkien_estate_limited_1937.jpg)