This morning I am thinking about space.

I worry constantly about giving people space. I hate feeling like an imposition, and for some reason, I feel like anything I ask other people to do for me is always, always an imposition. Even the smallest things: if I email a friend and I’m eager for them to write me back, I don’t want to ask them to do it, and I don’t want to hurry them or remind them that they haven’t written me back yet, because — that would be an imposition. I ask my wife, every night, what she wants for dinner, what she wants to watch if we’re going to watch TV; I never start with my opinions or my preferences, because I don’t want to influence her decision by pushing for what I want. And somehow I see simply stating, “I feel like tacos tonight” would be — pushing. Imposing. Rude.

I honestly do not know if this is because I am introverted, or overly polite, or timid, or too nice; or if this is something that everyone worries about, or at least most people, or just some. I think, in fact, that I am annoying with this: I think sometimes my wife would like me to just say, “Hey, we’re having tacos for dinner tonight, and then we’re going to watch The Umbrella Academy,” so that she doesn’t have to decide for both of us. Especially because I will usually go and get the groceries and make the tacos, if I am the one wanting that dinner. It should seem like less of an imposition if I am doing everything myself, and not asking other people to do things for me. I worry that my writing is an imposition, that I am too wordy or boring, and so asking people to read my work is rude and demanding. Somehow I never think that people enjoy reading my work and would do so voluntarily. Somehow I never think that I’m the one doing the heavy lifting here; that writing is hard, but reading what I write is probably pretty easy.

On some level this attitude is good; it keeps me humble and grateful. I never take anything for granted. (I’m sure I do, and I don’t know what it is, because I don’t think about it, because I take it for granted. This is the problem with being aware of what you are unaware of: you can’t be unless someone else points it out to you. So hey, if you know me, and you can tell me something I take for granted and am not grateful for, tell me, okay? If it’s not too much trouble. Thanks.) I think it is quite valuable in my teaching, because I do as much as I can to give control to my students. Because I don’t want to impose: I don’t want to assume that what I think is important is actually important for them, and what I think is fun is actually fun for them, and what I think is right is actually right for them. I am happy to offer my opinions — and if my wife asks what I want for dinner, I will tell her; sometimes, at least — but only as considerations, and only insofar as I can explain and argue for them. I think that sends a useful message and sets a positive example for my students, and I’m happy with that. I also think that everyone is constantly trying to control teenagers, and they need at least some adults in their lives who don’t do that to them, and I am glad when I can be one of those adults. I am also aware that I am a white man, and therefore my word gets taken over essentially anyone else’s, and so I try very hard not to be the one dominating the conversation or making all of the choices in a public/professional setting. I do not want my voice to drown out other people’s.

But I avoid imposing on others so much that I think I disappear sometimes. Which is too bad, mostly for me, but also because I’m a pretty good guy, with pretty reasonable opinions and mostly good taste; I can contribute a lot to most conversations and decisions. And I should do it more. I still like being consulted, so once I get to know people I hope they learn to ask me what I think, and then I will gladly say something; but I should also volunteer what I think, or what I want: as long as I don’t do it in an insistent, domineering, rude manner, it shouldn’t really be an imposition. Right? Just my opinion. Just an expression of my desires.

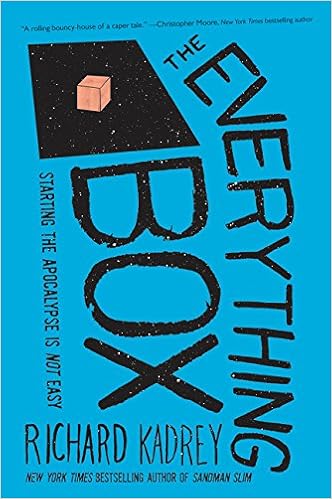

Hey: you all should buy my book, if you haven’t. And if you have, you should read it. And if you’ve read it, you should rate or review it on the site where you bought it, or on Goodreads. And you should like this post, and subscribe to this blog. And you should comment, if you have comments. You should tell me what you think. I am curious. I would like to know.

If it’s not asking too much.

Here: links to make it easier.

My book on Lulu.com, where if you don’t mind signing up for a new account with them, I get about twenty times more money because I don’t have to give most of the cover price to Amazon.

My book in ebook format on Smashwords, which links to a dozen other sites where you can buy it in whatever ebook format you prefer. Note that the ebook is broken into four smaller parts, and is appreciably cheaper than the paperback.

My book listing on Goodreads, though there are also listings for the individual ebooks if you want to rate and review those.